Decimal currency has been part of the fabric of societies around the world for centuries. Yet, however ordinary seeing a figure like £9.99 may seem to us today, Britain will only celebrate its first fifty years since going decimal this year, on 15th February 2021.

Britain finally drops LSD

The UK had, for centuries, used the system of pounds, shillings and pence – or ‘LSD’, from the Latin denominations librae, solidi and denarii. In fact, the ancient system had once existed across Western Europe; but by the middle of the 20th century, the spread of decimalisation across Europe had left Britain its last island outpost. (The double entendre with the psychedelic drug was not lost on people at the time. The government’s own secret military trials of LSD, beginning in 1964, were codenamed Moneybags, Small Change and Recount.)

Switching to decimal currency so late in the day would prove to be a monumental shift, involving political wrangling, arguments over design, long-range weather forecasts and even psychological tests carried out on the public. This was a change being applied wholesale to an entire economic system; the fact that it didn’t cause major national disruption is testament to how truly well-planned the switchover was.

The change to decimal currency was certainly a long time coming. In 1824, the MP Sir John Wrottesley shared his “strong conviction” with Parliament that Britain should go decimal. His suggestion was rejected for fear of the uncertainty and instability such a change would cause. The first decimal coin – the florin, representing one-tenth of £1 – was introduced 25 years later. Royal Commissions in 1856 and 1918 rejected the idea again. By 1960, pressure from industry, and the success of the system virtually everywhere else, led the government to begin preparations for Britain’s own slow transition. The government created a decimalisation committee in 1961, chaired by Lord Halsbury, and set them to work.

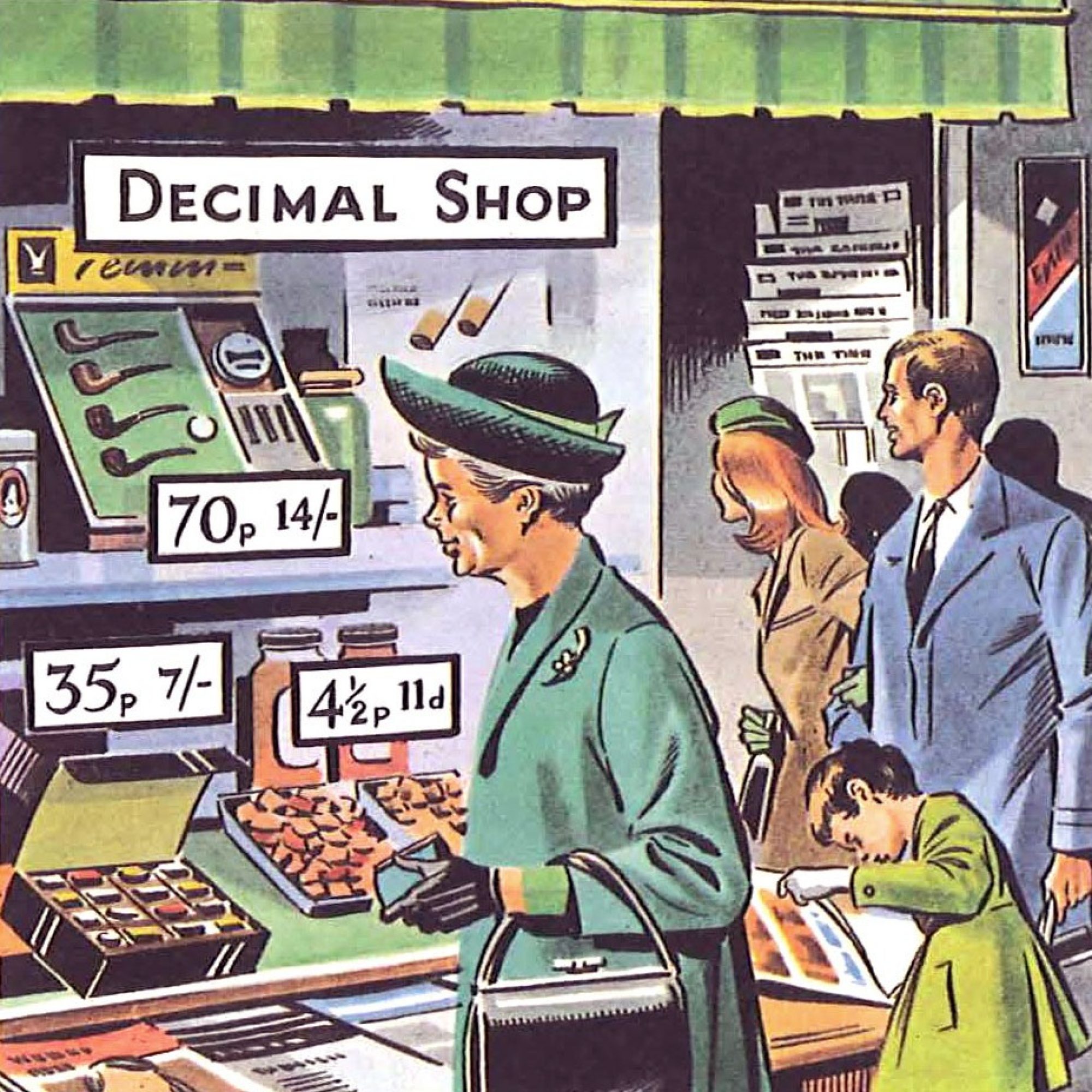

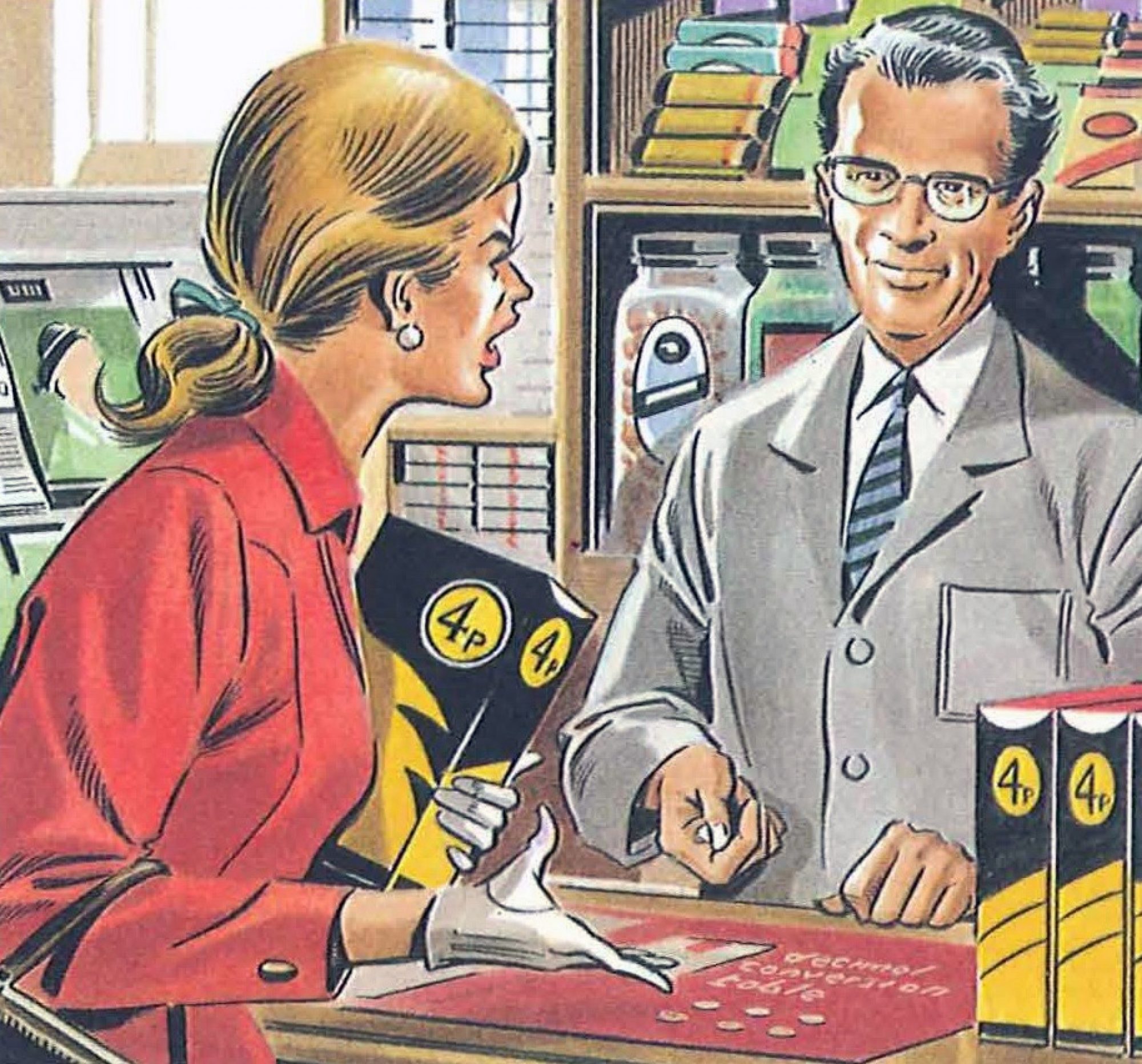

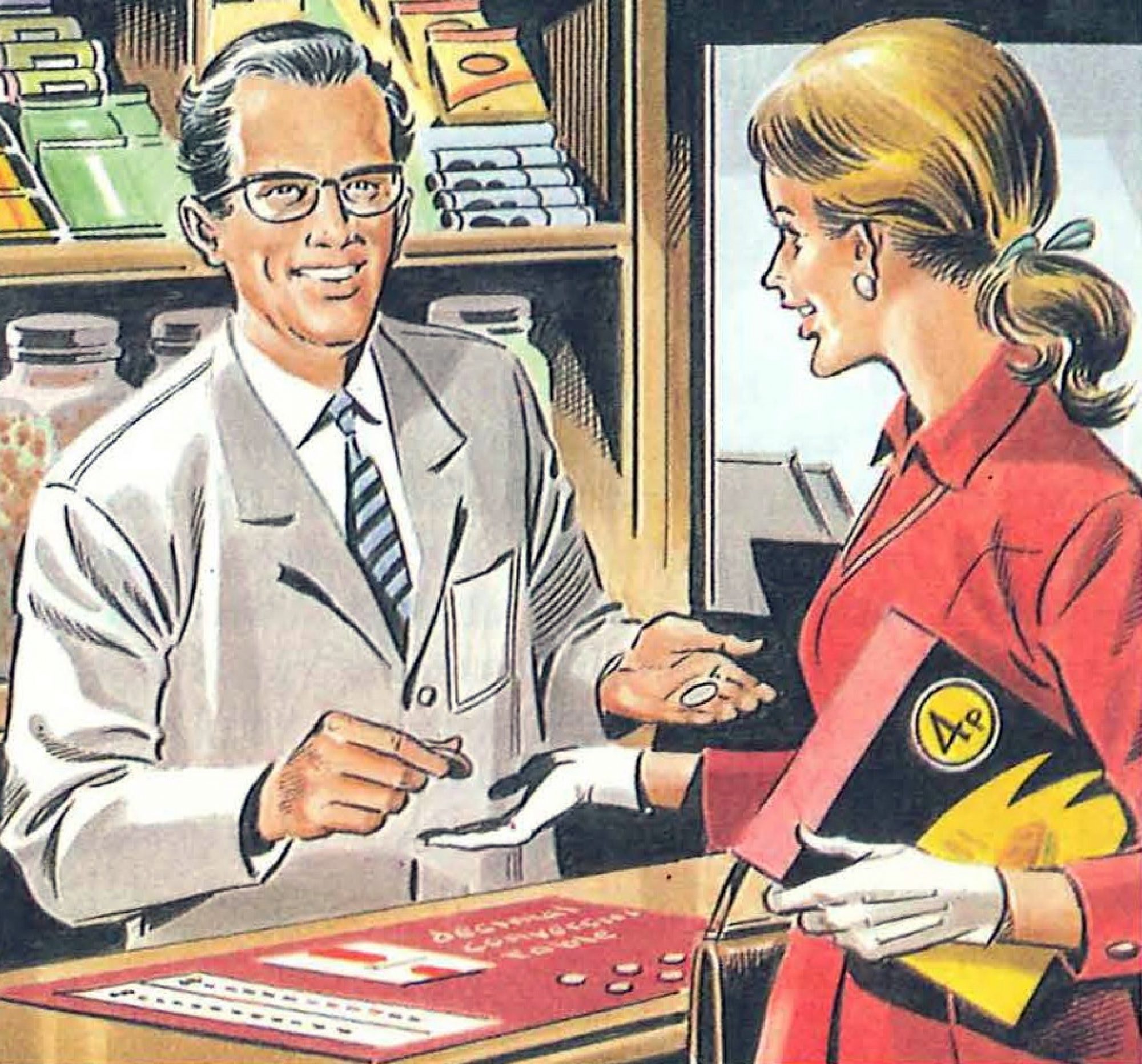

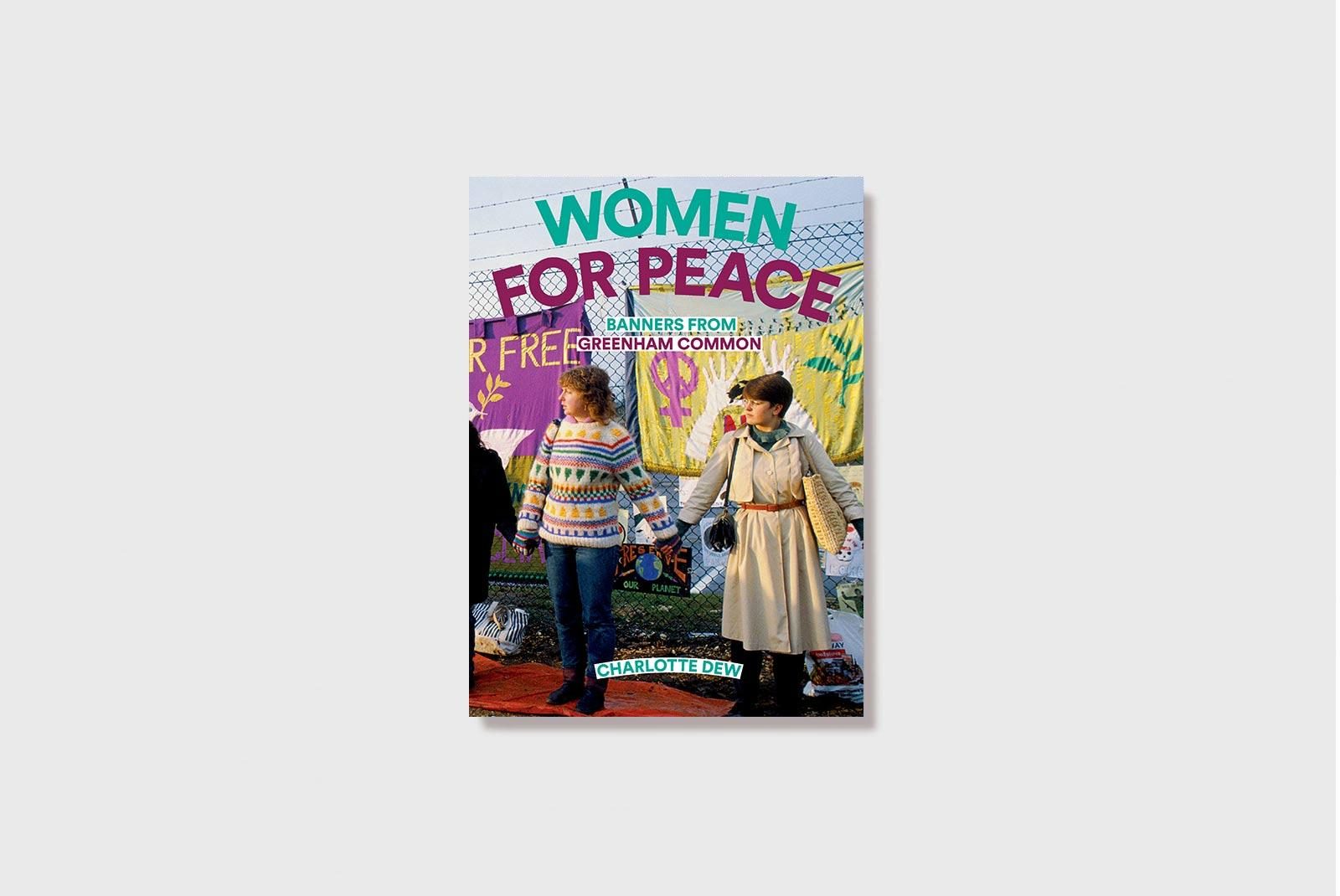

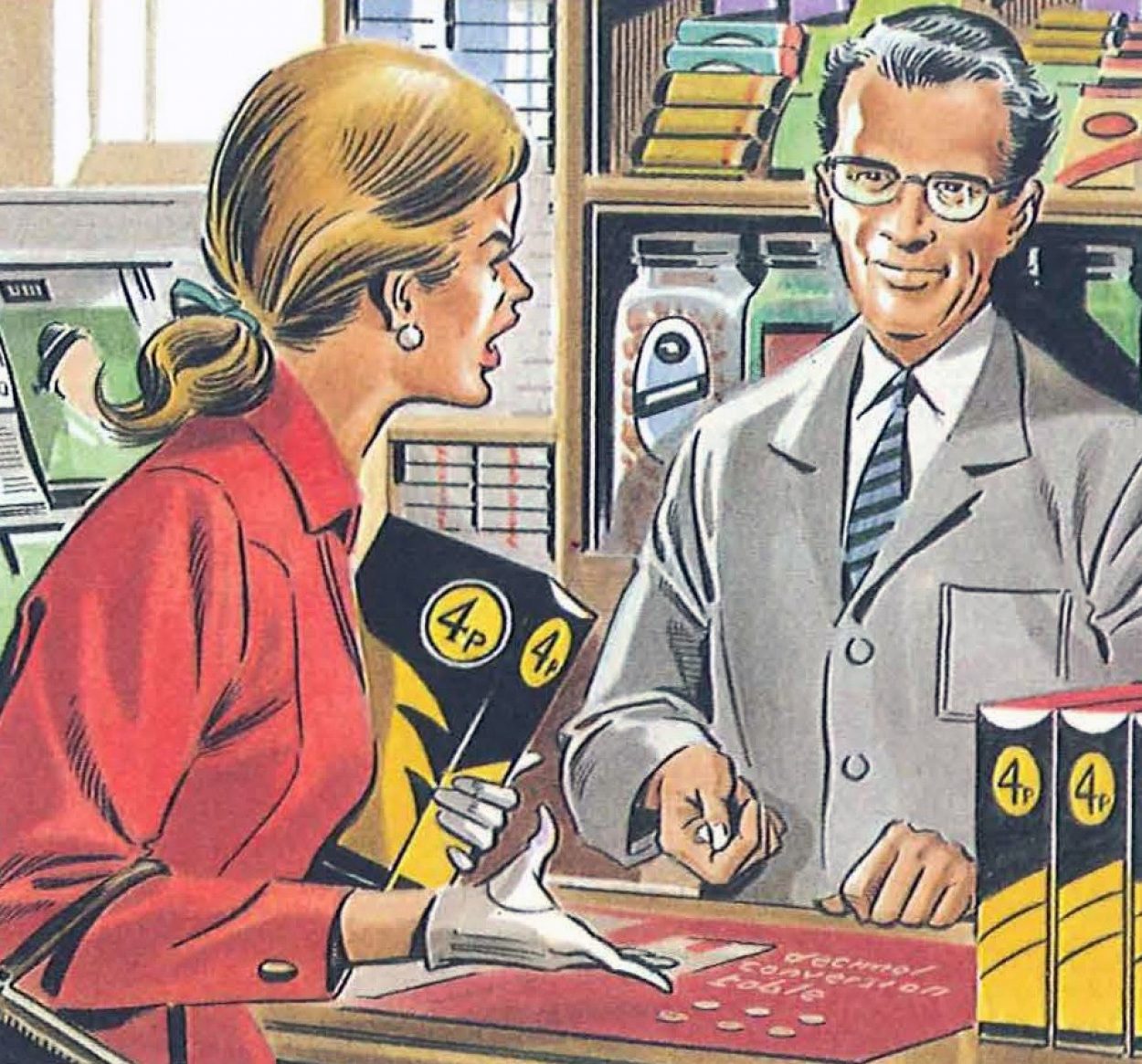

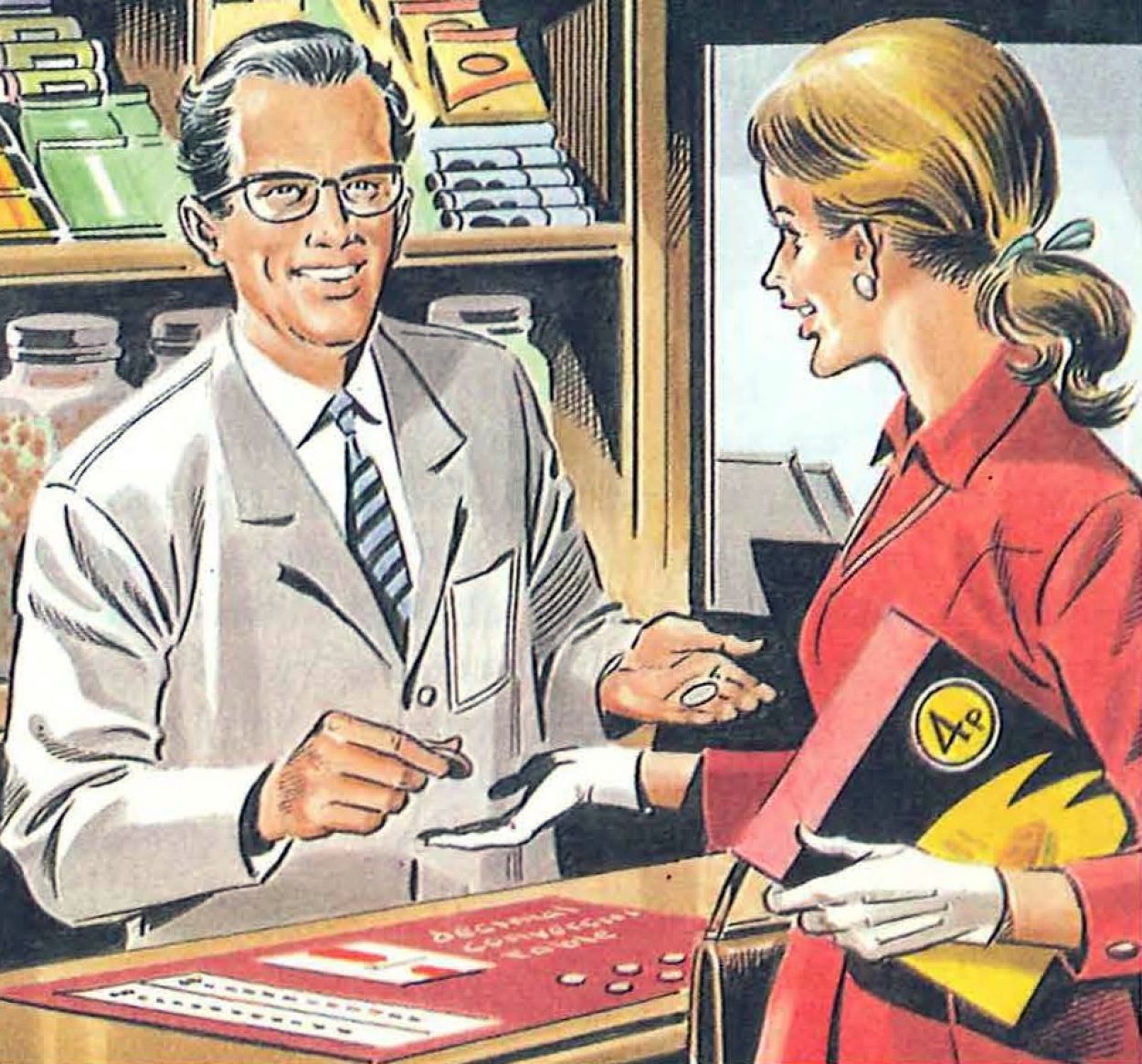

Image from 'Decimal Currency for Retailers in Tobacco'.

Splitting the difference

Inventing a new currency isn’t as straightforward as you might think. The committee was starting from a blank canvas. For a start, they had to decide how to divide up the currency. Today, splitting £1 into 100 pence seems intuitive, perhaps even obvious. However, former ‘LSD’ countries – such as Australia, New Zealand and South Africa – had opted to create a new unit, the dollar, and based it on 10 shillings rather than one pound. Then there were the smaller divisions: the 1918 commission had favoured dividing each pound into 1,000 ‘mills’; the 1960s committee favoured 100 cents. By 1966, however, the committee had settled on retaining the pound and dividing it into 100 ‘new pennies’.

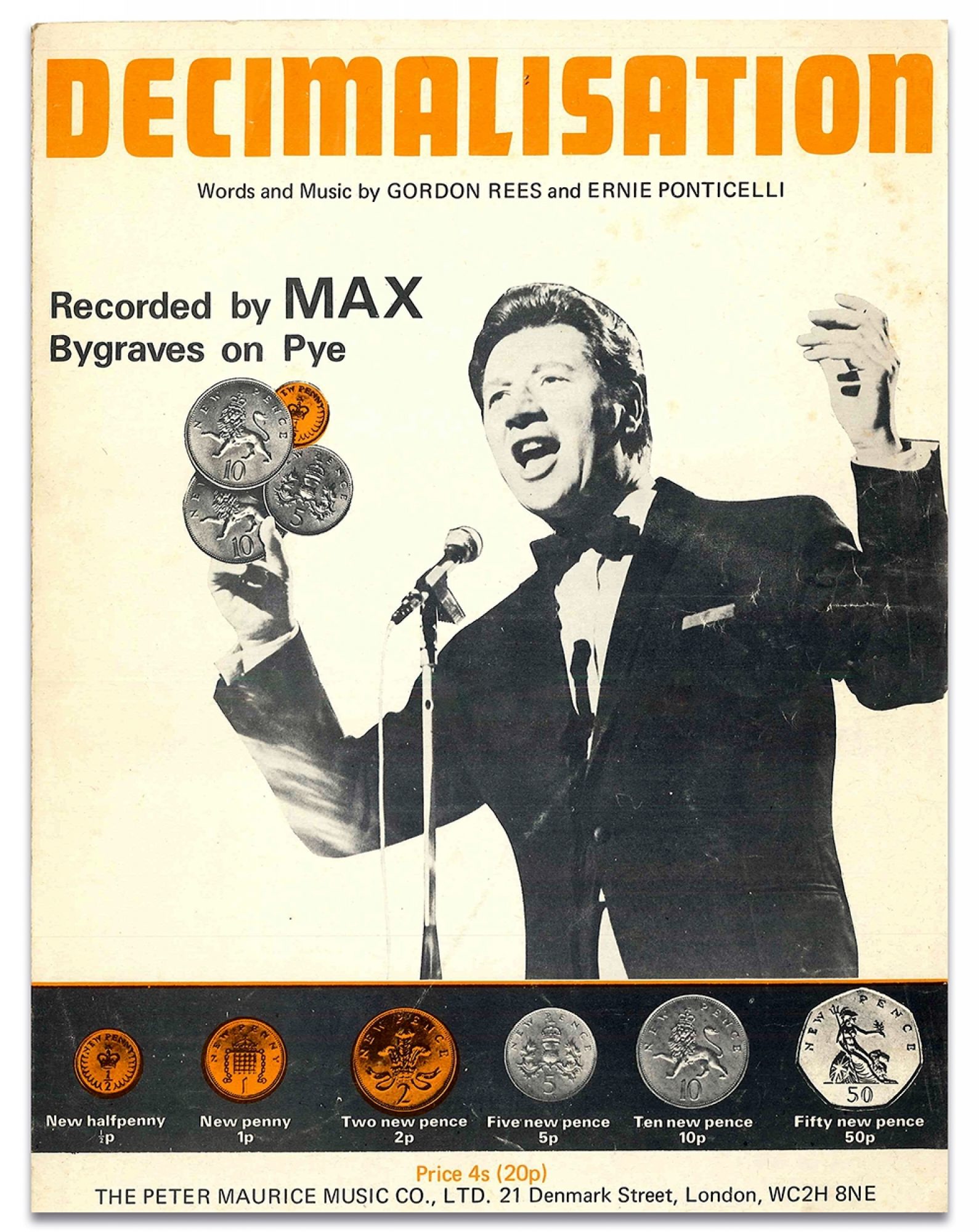

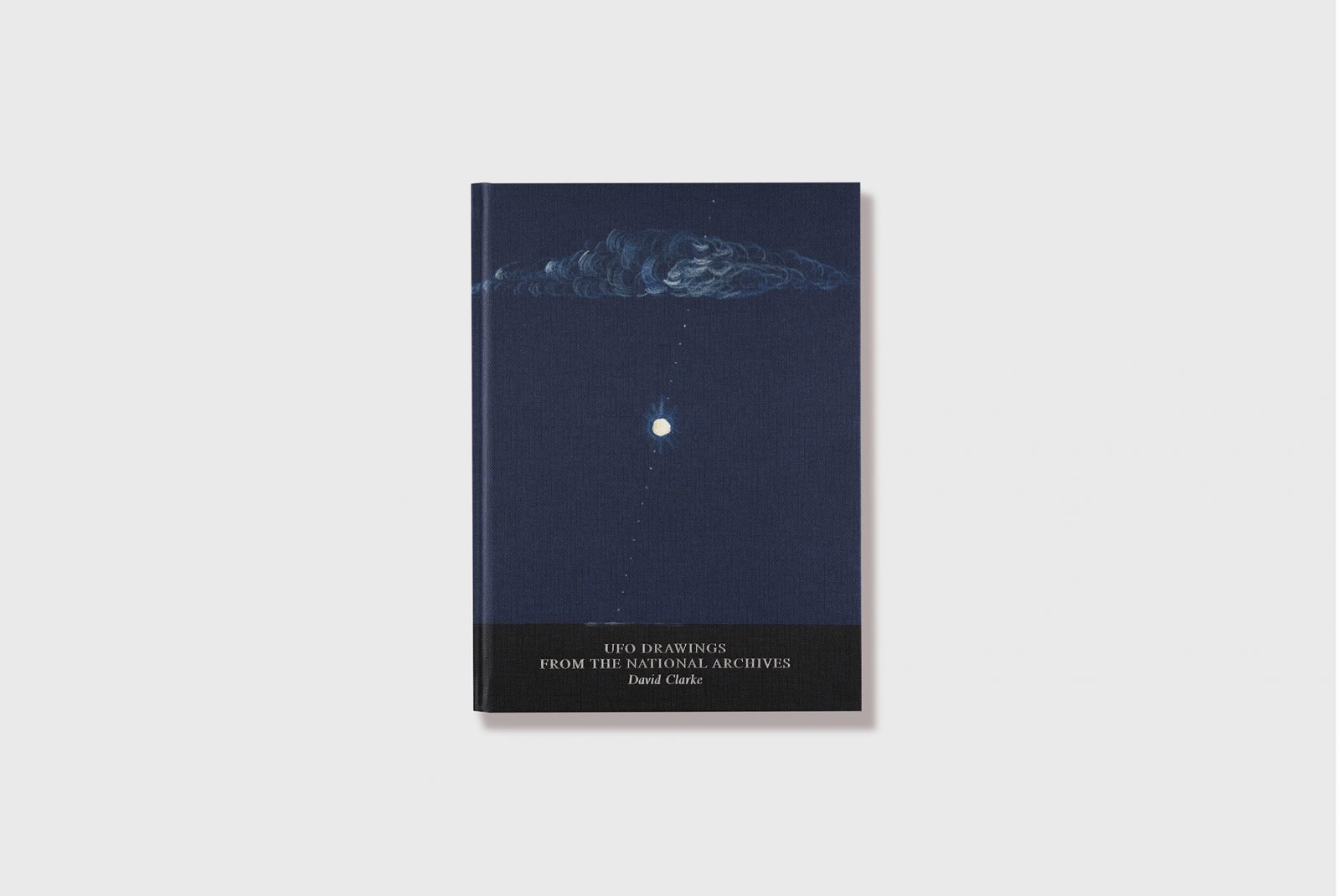

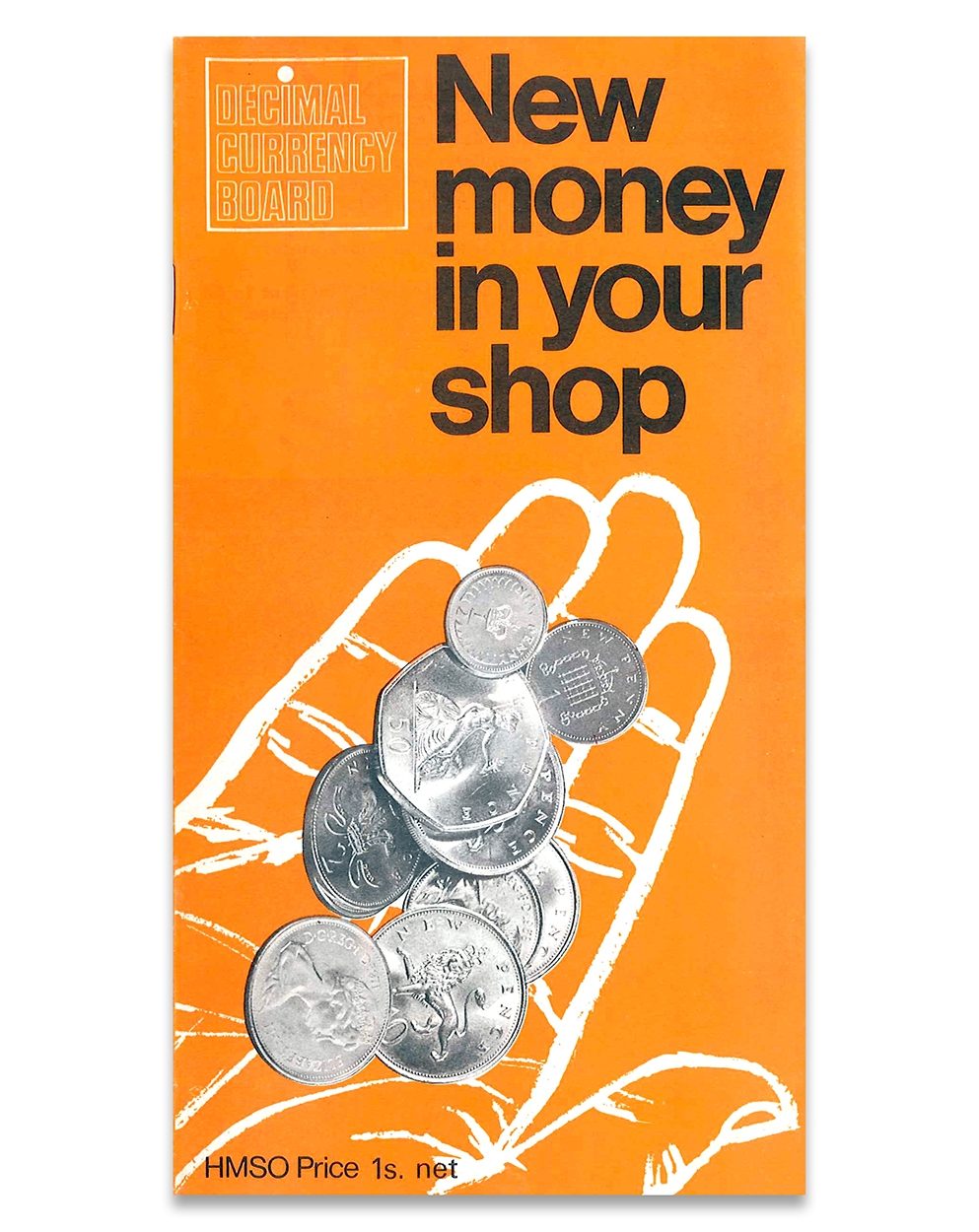

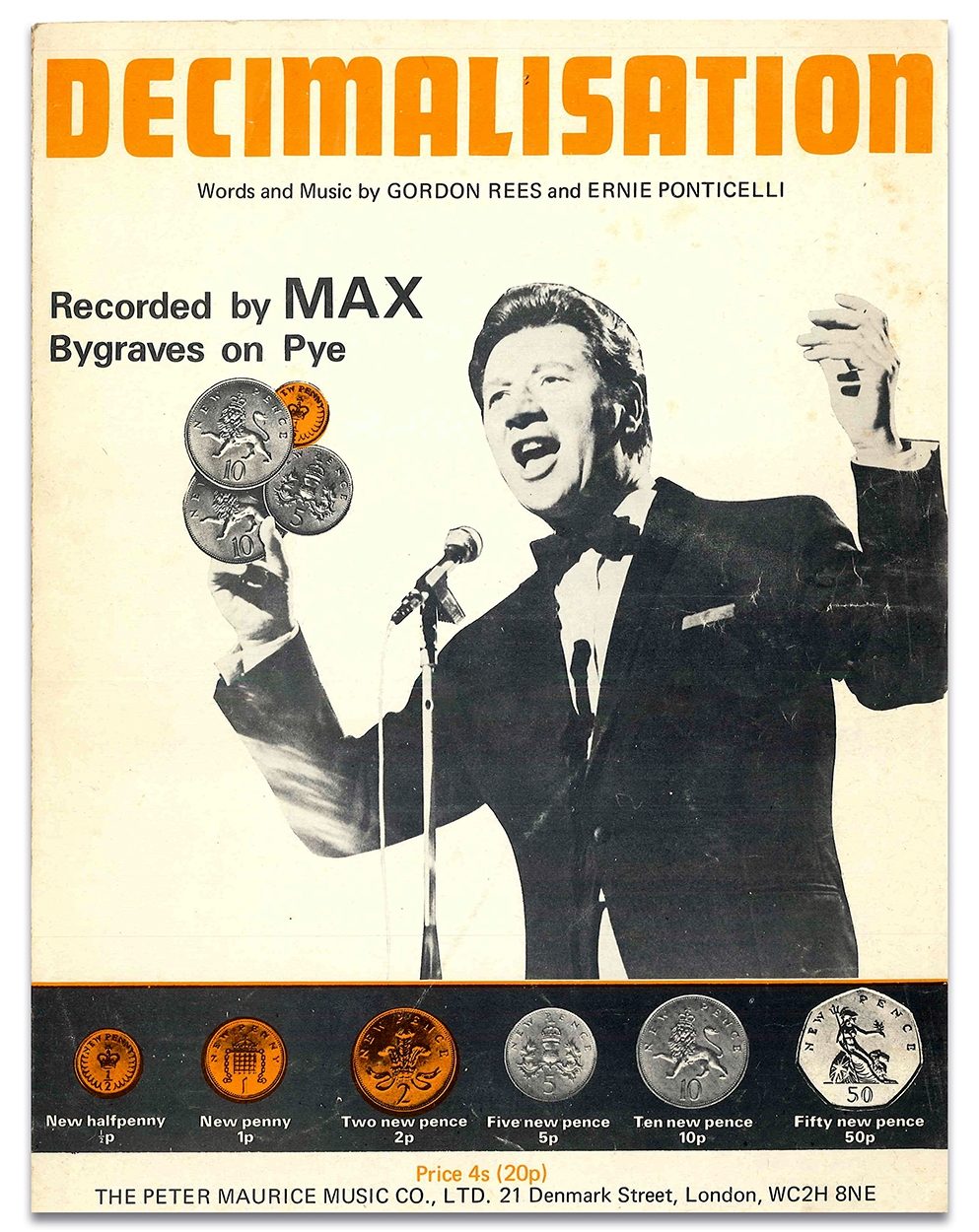

Accepting its recommendations, the government set a date for Decimal Day, or ‘D-Day’: 15th February 1971. A new body, the Decimal Currency Board, was created to manage the publicity and logistics ahead of the event. With the help of the Central Office of Information – the government’s in-house publicity team – the Board got to work on producing colourful information which would educate and inform the public and industry. They wrote press releases, ran poster campaigns, and created films and records, even commissioning a new song about decimalisation from the variety performer Max Bygraves. They worked with the BBC to run a public education series, Decimal Five, which featured new music by The Scaffold (of 'Lily the Pink' fame). They helped prepare audio records for training workers en masse, and distributed booklets like Your Guide to Decimal Money to the public, and New Money in Your Shop to retailers.

Bringing in the men in white coats

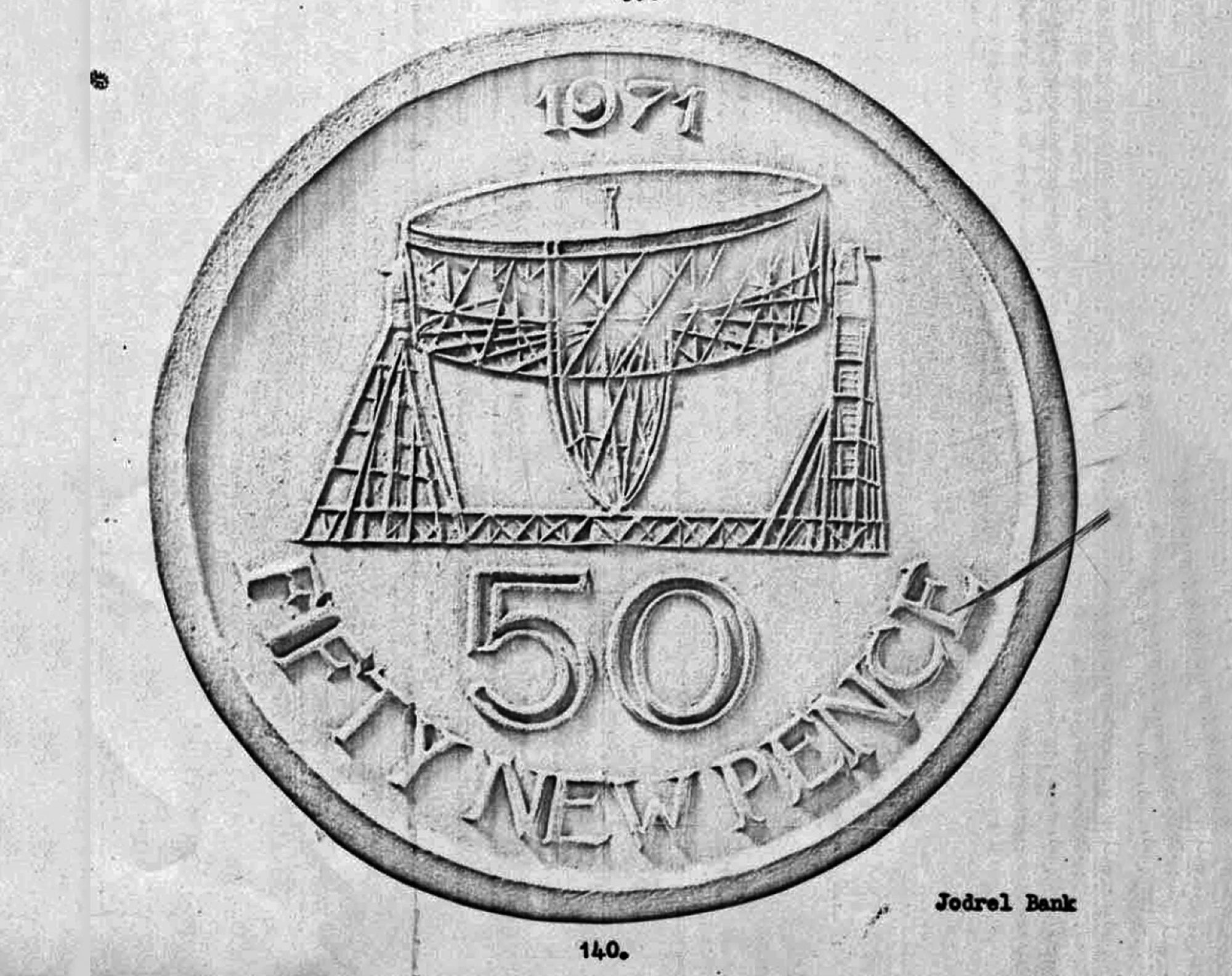

Meanwhile, at the Royal Mint, designers were hard at work, creating new coins under a veil of secrecy. In particular, they were interested in creating a design for the new 50p coin – the highest-value decimal coin being introduced on D-Day – that would make it easy to recognise quickly. It couldn’t be round, as the intention was to make it distinct from lower-value coins. So, armed with a set of polygonal sample coins from the Mint, the Decimal Currency Board brought in experts from the Medical Research Council’s Applied Psychology Unit to test each shape with ordinary members of the public. Their findings were unequivocal: a coin with ten straight sides performed best in every respect. “Ten-sided coins were generally counted faster and with greater accuracy than the four-, seven- or twelve-sided coins, both for vision and for feel alone,” the report concluded.

If you have a 50p to hand, you might spot a problem here: the coin we ended up with only has seven sides, so what happened to the fantastic ten-sided coin? In fact, the psychologists’ findings were overruled by industry demands: a coin with seven slightly curved sides – technically, an ‘equilateral curve heptagon’ – would work more smoothly in coin-operated machines, so this was recommended for adoption. This decision to go against the evidence did not go unnoticed. The secretary of the Decimal Currency Board complained of experiencing “a great deal of embarrassment” from a magazine article titled “Seven-sided coin madness”, and there was plenty of correspondence between the Board and the Medical Research Council on how best to address the issue. There are even hints that the sinister seven-sidedness cover-up continues: as of 2020, the Royal Mint still claims on its website that the seven-sided design tested better than the ten-sided one.

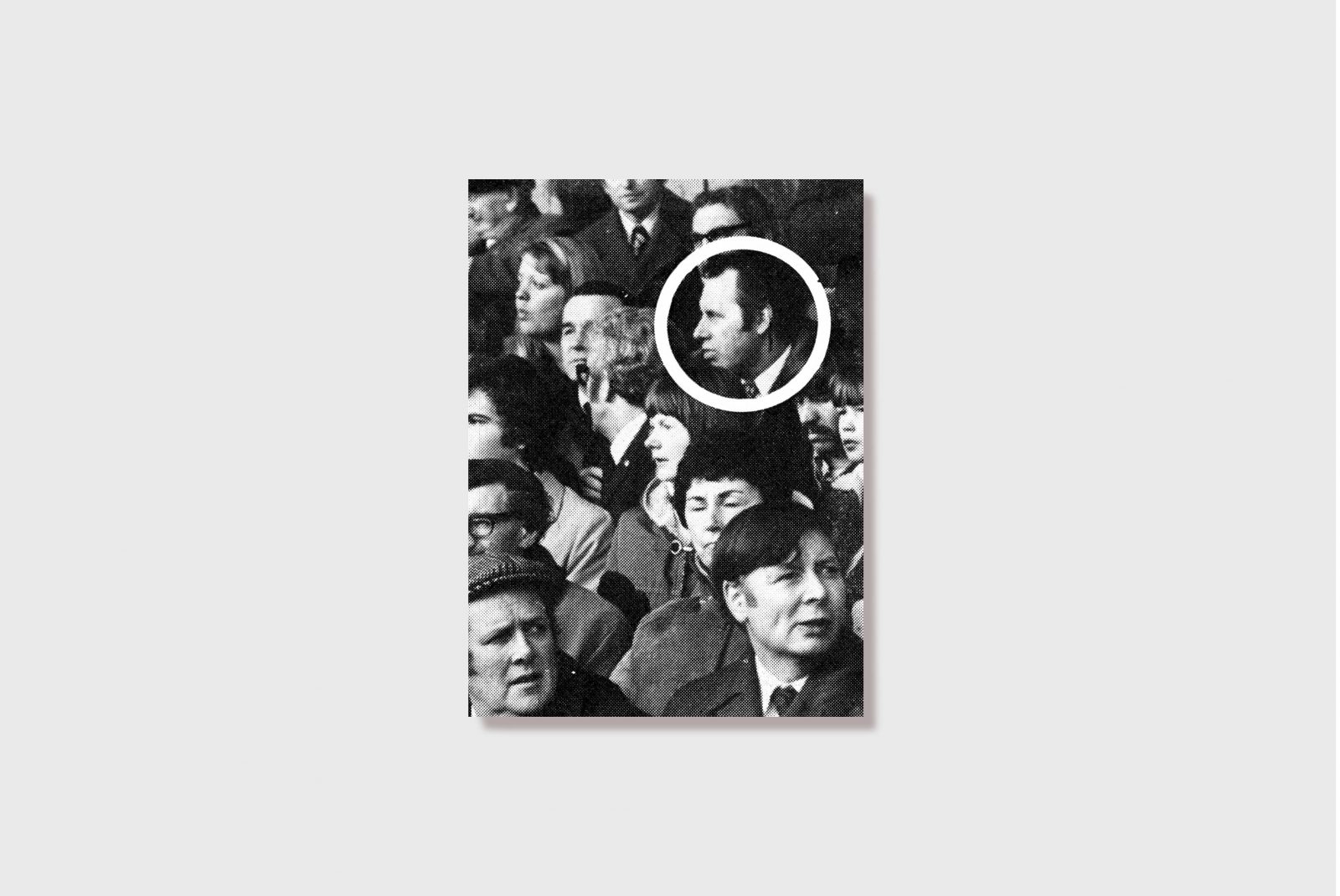

Above: Test coins prepared by the Royal Mint for the psychological tests

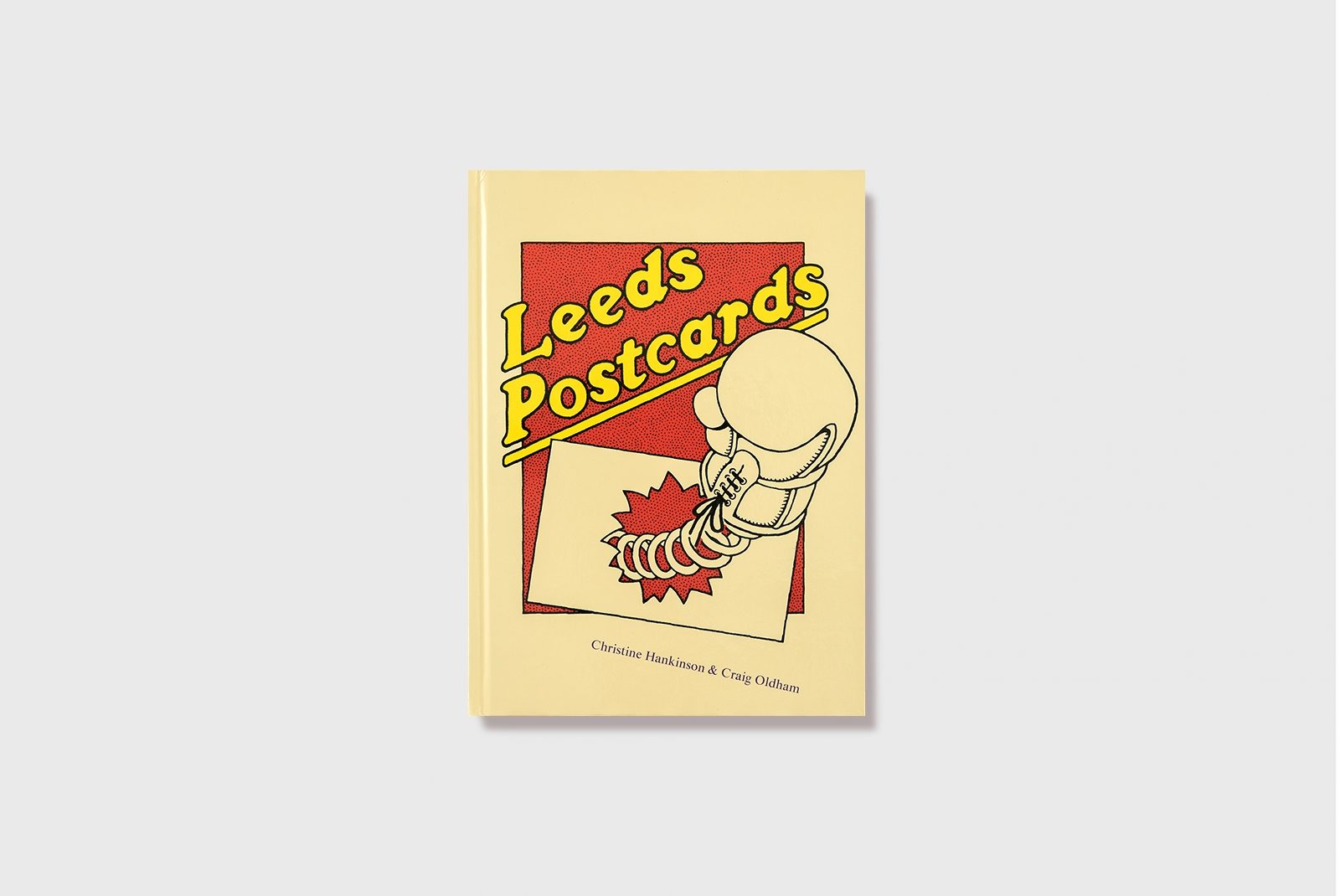

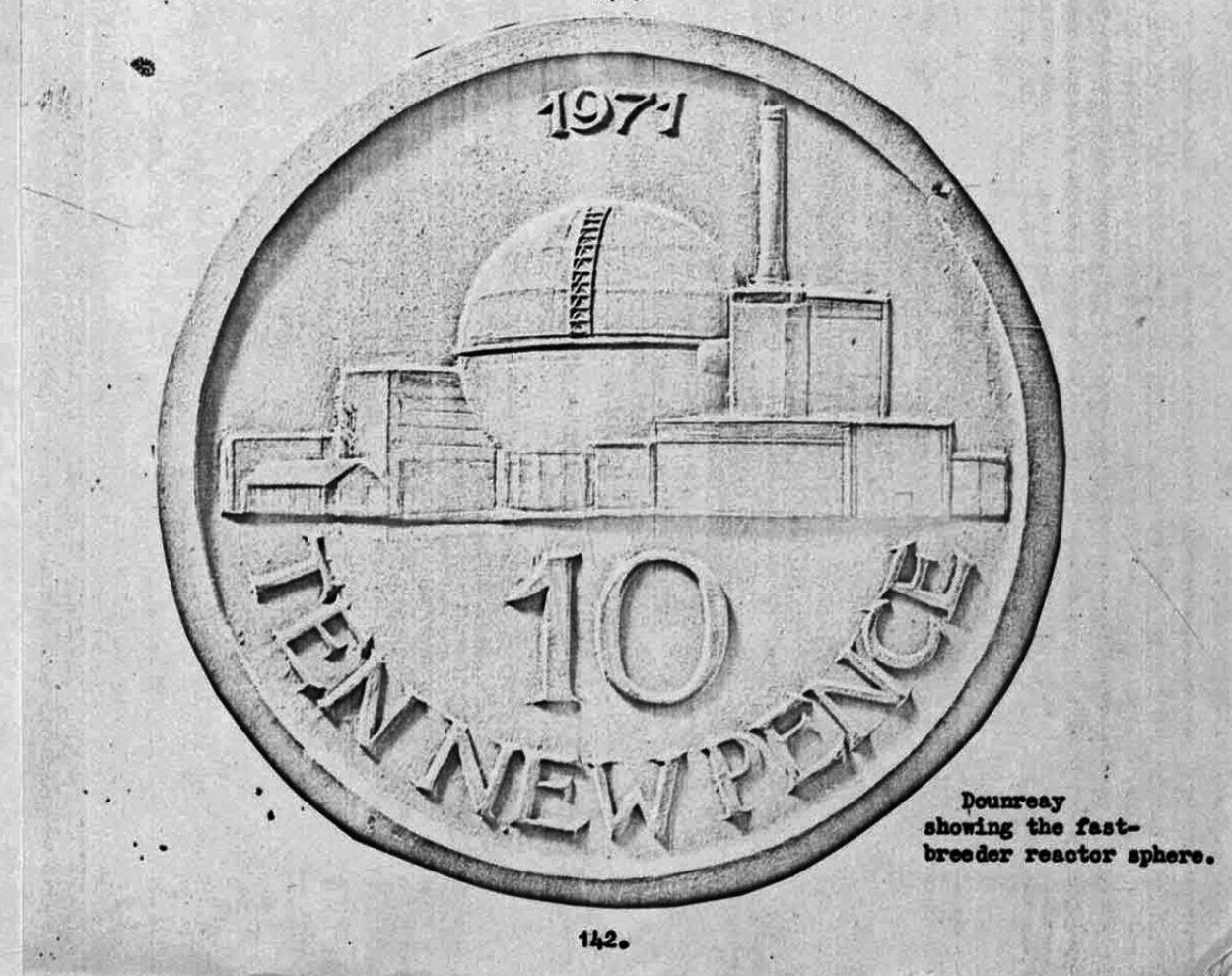

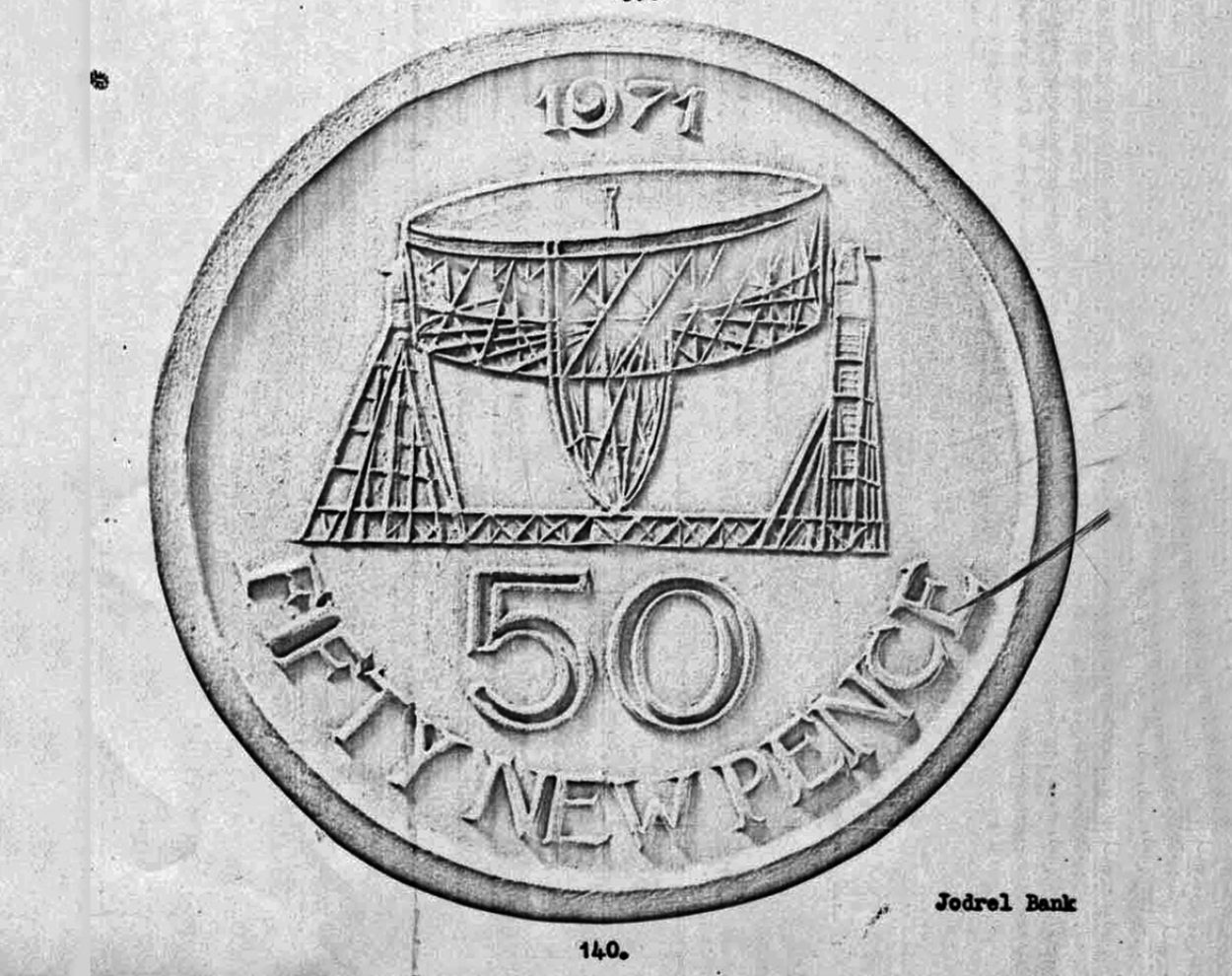

Below: Shortlisted entries from the design competition for the new decimal coins by Paul Vincze (10p and 50p) and Geoffrey Colley (1p and 1/2p). The winning designs which became familiar to millions were created by Christopher Ironside. Crown Copyright.

Anxiety builds

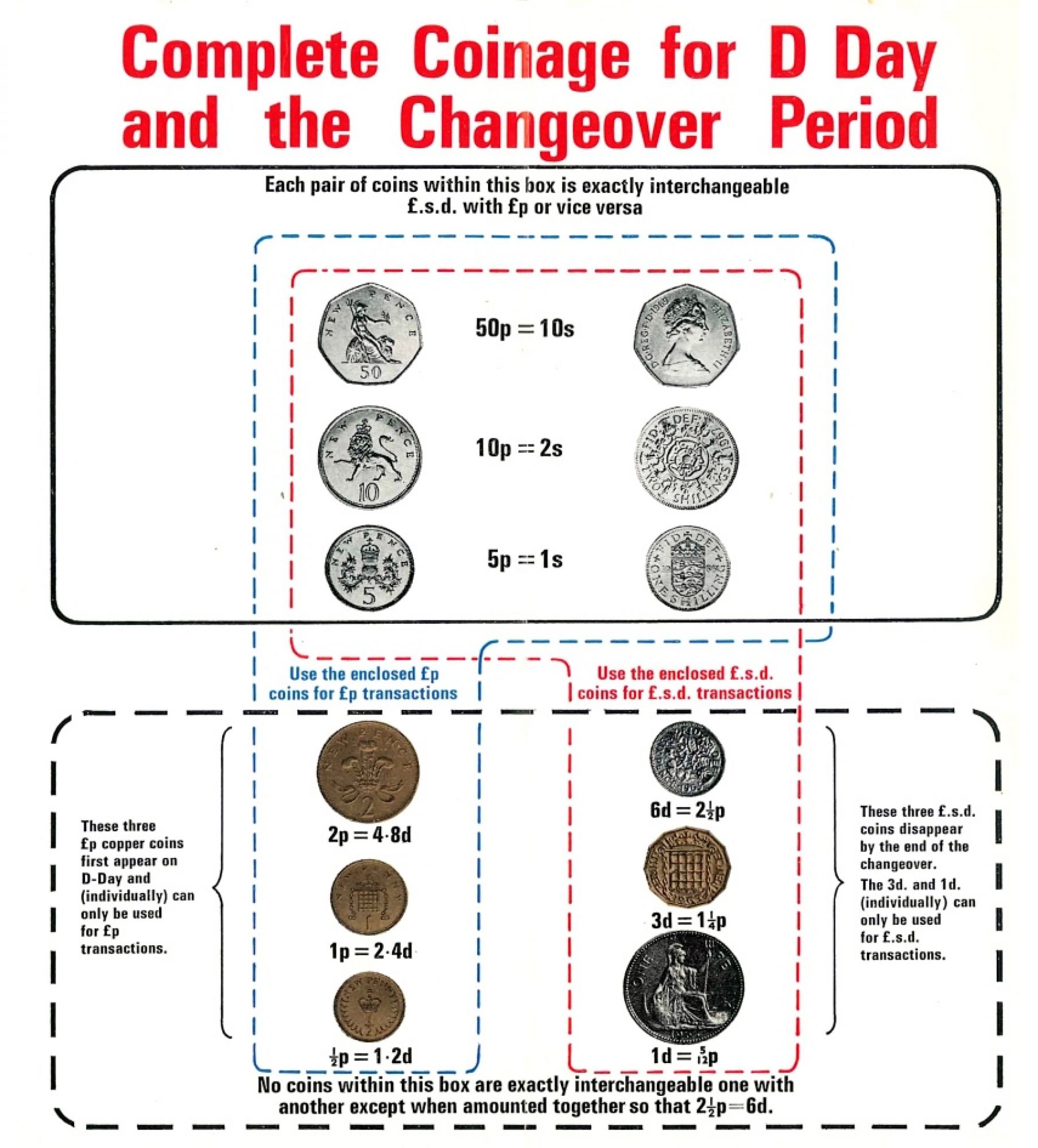

As D-Day approached, the British public were, in fact, already using some decimal coinage. The 10p and 5p coins had arrived in 1968, being identical in size and value to the florin and shilling. The machine-friendly, seven-sided 50p – worth 10 shillings – had been launched in 1969. Since, in 1960s Britain, day-to-day shopping was still not carried out by men, the Decimal Currency Board conducted market research into how concerned women were about the switch. Their anxieties over decimalisation had fallen after the introduction of the first two coins, but were steadily on the rise again, with nearly half worried about some aspect of D-Day. Some feared businesses would take advantage of the change: “How many people will try to make a few bob on the side by fooling old people?” asked one woman. Another called the situation “hopeless”, adding “we’ll take ten times as long doing shopping as we do now”. “There’s no way of making a protest about it – it annoys me intensely,” claimed another, her objection now recorded, ironically, for posterity.

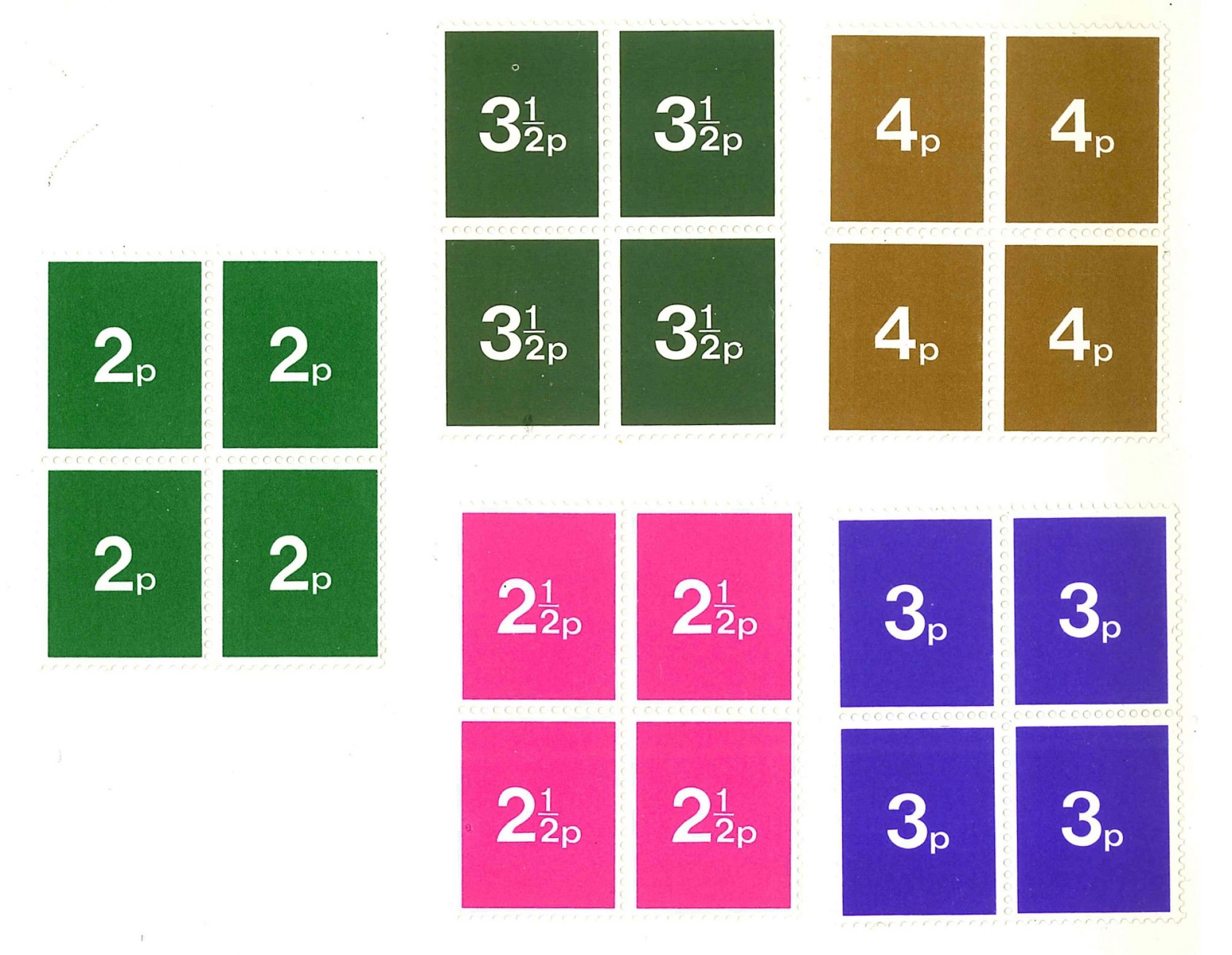

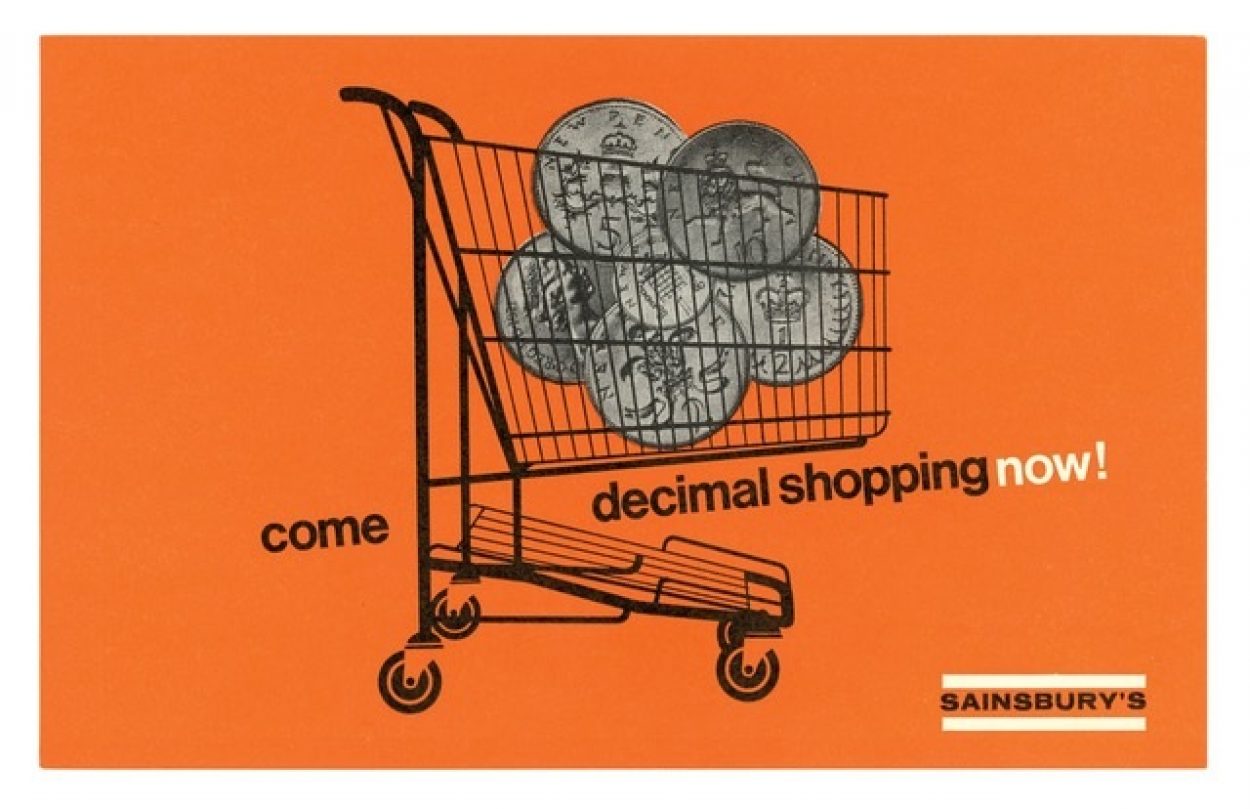

This feedback led to a new publicity blitz by the Decimal Currency Board. They took out print ads sharing ‘simple guides’ to the new currency. They also considered ads in the form of quizzes: “Just over a year to Decimal Day… How do YOU score in this Decimal Quiz?” A film which specifically addressed the concerns of women and older people, Granny Gets the Point, was commissioned and broadcast on ITV repeatedly in the lead-up to D-Day. Industry began preparing, too. Simplified decimal stamps were issued to Post Office staff for training purposes, and the supermarket Fine Fare ran a decimal-only shop – albeit as a publicity stunt during an ‘exhibition of the future’.

Late in 1970, the government became concerned that the weather might scupper D-Day. They engaged the services of the Met Office to create long-range weather forecasts to ensure there would be no storms or snow. As the critical day approached, the Met Office sent daily weather updates to the Decimal Currency Board. With four days to go, the final report advised the committee: “Adverse weather conditions are no longer a factor which could cause us any problem”. Lord Fiske, the Board’s chairman, simply replied: “Splendid.”

In the last few weeks before the change, the BBC’s Today programme brought in a schoolboy, Sebastian Head, to help explain the new system. In an article headlined “RADIO AID BY BOY ON DECIMALS”, Sebastian, an aspiring musician, explained: “I think the most sensible thing is not to worry about converting, but to try thinking in terms of new money from the start.” He even recorded a song on for Pye Records – D.E.C.I.M.A.L. (click through to listen) – which was issued as a promotional 7-inch record, but, perhaps fortunately, never made it into the charts.

Above: Training stamps for Post Office staff

Below: Leaflets by Sainsbury's Design Team, © The Sainsbury Archive, Museum of London Docklands.

Beneath that: Conversion table from training materials for British Rail staff.

“The Non-Event of 1971”

With all the commotion of the build-up to D-Day, the day itself came and went with little incident. Lord Fiske had predicted that decimalisation would be “the non-event of 1971”, and he was proved right. A government system let shop managers report what was happening on the ground, giving ministers a national picture of the public’s reaction to the new coinage. Thanks to the years of careful preparation, though, the public ‘got the point’.

D-Day stayed in the news for a short while. The press gave the tiny new halfpenny a nickname: the ‘tiddler’. The Daily Sketch went further, asking its readers to suggest names for the other coins. They came up with the ‘maxi’, ‘half-century’ or ‘gong’ for the 50p; the ‘florry’ or ‘flora’ for the florinesque 10p. The thistle-adorned five pence piece became the ‘Scotty’; the two pence coin, the ‘Charlie’, as it featured the Prince of Wales’s crest. Nicknames mooted for pennies included ‘oncers’, ‘solos’ and ‘sprats’. Needless to say, none of these caught on.

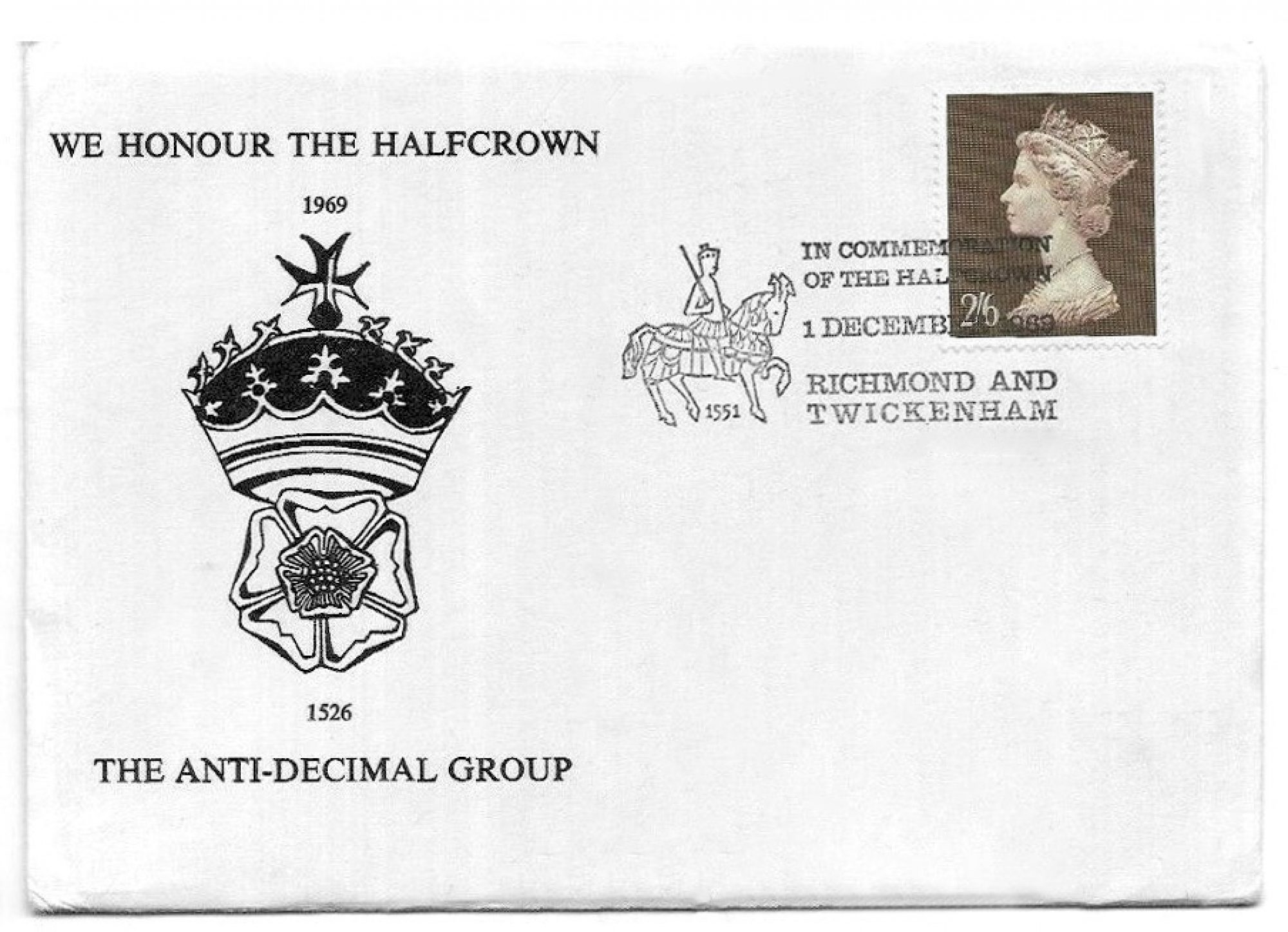

There was some opposition to the change. The Anti-Decimal Group lobbied in vain to reverse the decision to go decimal, issuing their own ‘last day cover’ to honour the passing of the half-crown coin, when it was withdrawn from circulation. The Times, tongue firmly in cheek, referred to the campaigners as 'anti-decimal terrorists'.

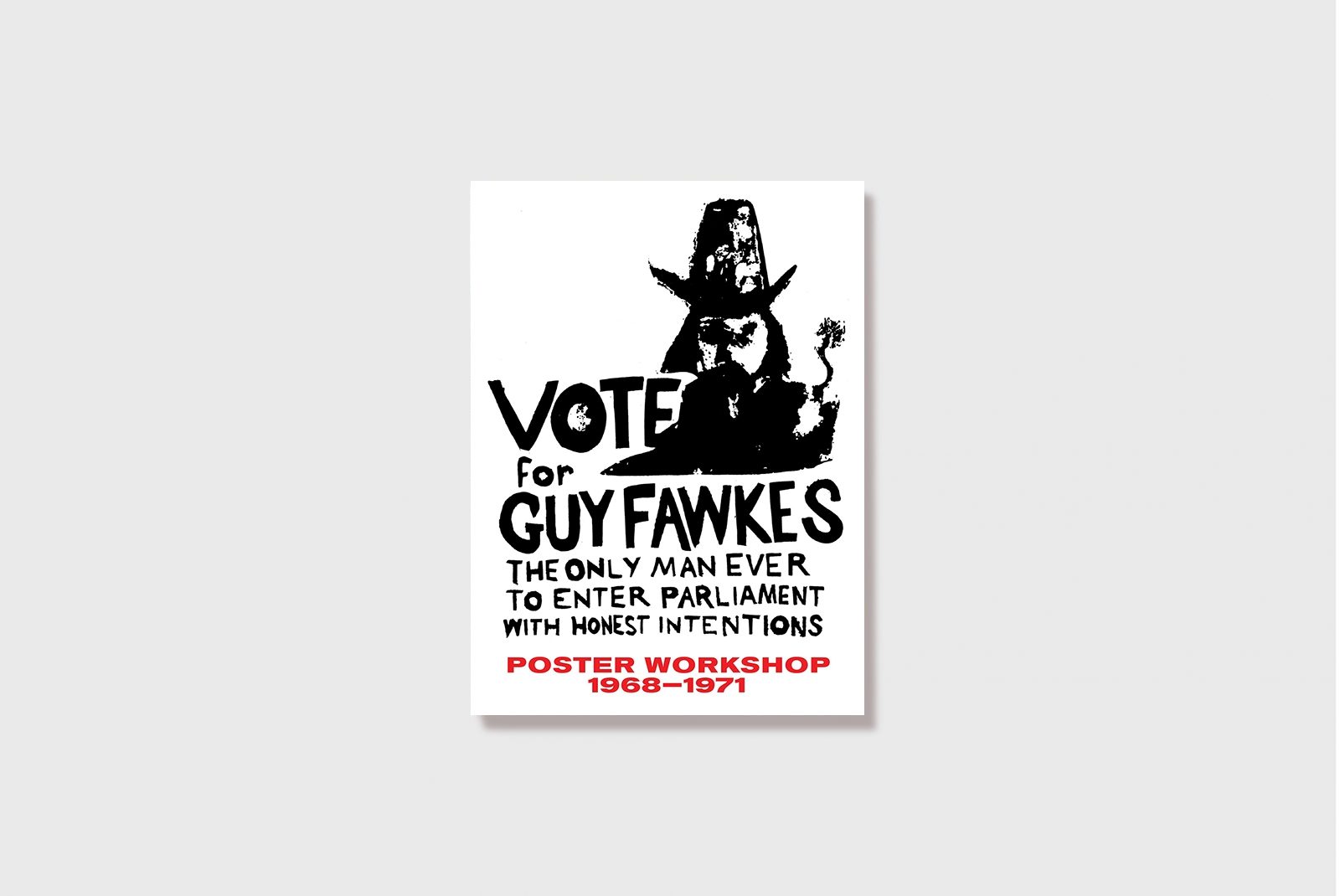

'Last day cover' for the Half Crown.

They’re out to kill the tiddler!

There was also opposition to the 'change' itself. Despite its affectionate nickname, the tiddler drew immediate and widespread dislike. At about half the size of a one penny coin, the coin was light and insubstantial, and the public did not warm to it. Just one day after it was introduced, the Evening News proclaimed: “THEY’RE OUT TO KILL THE TIDDLER!”. Some banks, pubs and shops refused to accept it. There were even claims that British Home Stores (BHS) – then a significant national retailer – were rejecting the coin. The Anti-Decimal Group said its unpopular design was a deliberate ploy to kill it off as quickly as possible, calling it an “impurity in the decimal system” – and tapping into the more widespread public fear that decimalisation was a cover for pushing up prices.

The strength of opposition to the new halfpenny was significant enough to cause serious concern within government – particularly since a billion had already been minted. Publicly, the Treasury issued press releases defending the coin; in private, they sought reassurance that the trouble was overblown. BHS assured the government that they were not “knocking the ½p, and indeed are not anti it”. The Cocoa, Chocolate and Confectionary Alliance issued its own statement supporting the tiddler, pointing out it was “essential to the pricing of confectionery”.

Armed with the reassurances of industry, and the Treasury’s view that the halfpenny had an important economic role to play, the Decimal Currency Board went on the offensive. Just two days after D-Day, Lord Fiske was back in the papers, saying: “The tiddler is here to stay”. In spite of this, the public never warmed to the coin. It drew ire from across the political spectrum; Tory politician Janet Fookes bemoaned the difficulty which her elderly and arthritic constituents had handling the halfpenny, while Labour MP Marcus Lipton called it a “wretched little coin”. Ray Carter MP warned the Chancellor that, one week in, “some retailers, services and manufacturers already regard it as obsolete”. In fact, the unloved tiddler would cling on for another ten years; its fate was finally sealed when it became more costly to produce than its face value.

Lord Fiske’s estimation that decimalisation would be a ‘non-event’ was correct: D-Day came and went without any significant hurdles. The government effected change on a scale that could have altered the fabric of society and caused major economic and political problems. Instead, they took their time, thought things through, and brought in experts. The work of the Decimal Currency Board, together with the designers and publicists of the Central Office of Information, helped ensure the public was well-educated, that industry was ready for the change, and that everything ran like clockwork. Fifty years on, it’s hard not to wonder where it all went wrong.

Taras Young is the author of Nuclear War In The UK, in our Irregulars series.