In the depths of the British Library Sound Archive lies a wonderful treasure trove of illicit audio recordings...

This is the British Phonographic Institute donation of bootleg vinyl records, CDs and cassettes given to the library in 2002. Some are filed, labelled and numbered neatly on the Archive’s rolling shelving systems; others await their turn in the Sisyphean task the sound archive faces to catalogue its continual flow of acquisitions (currently over 3.5 million recordings).

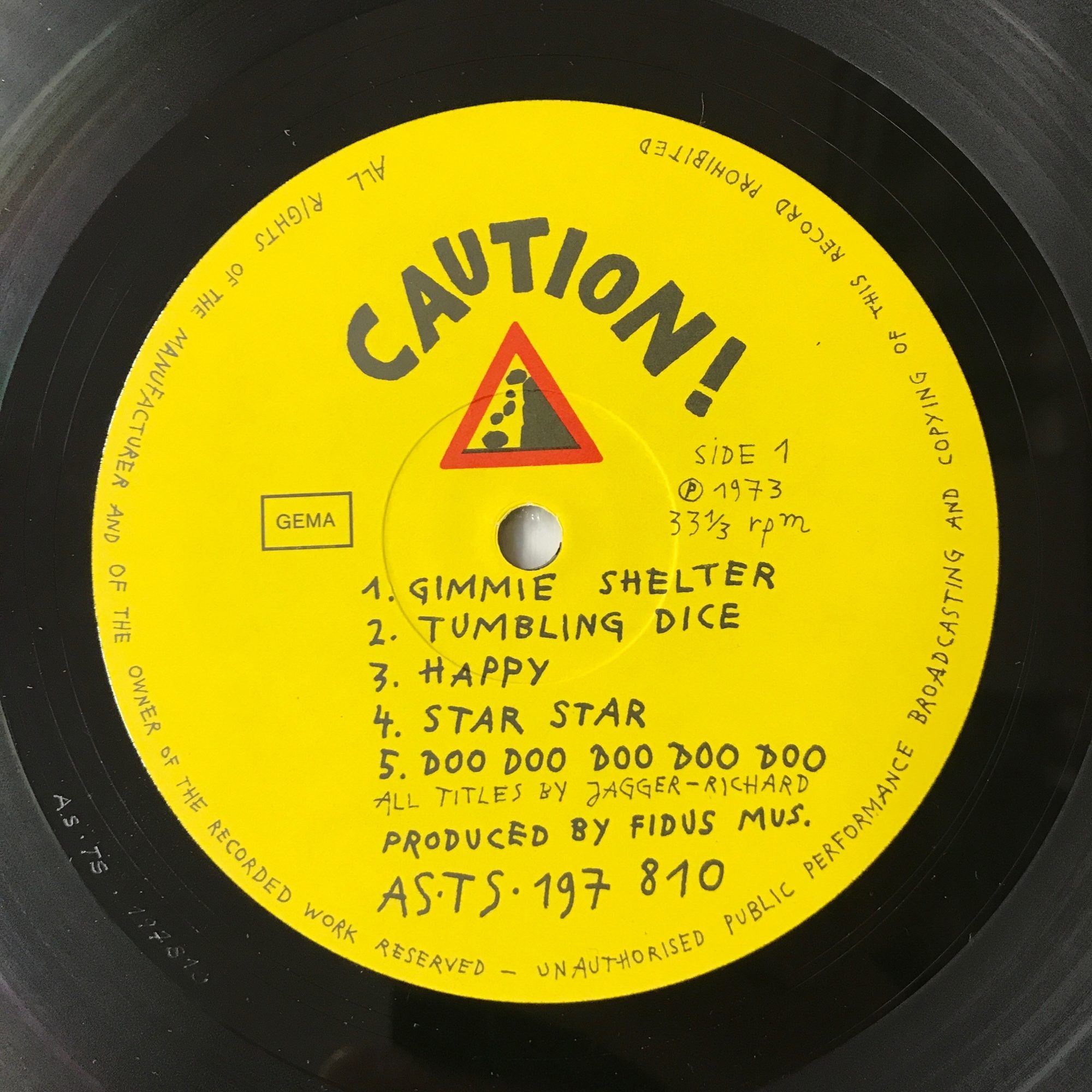

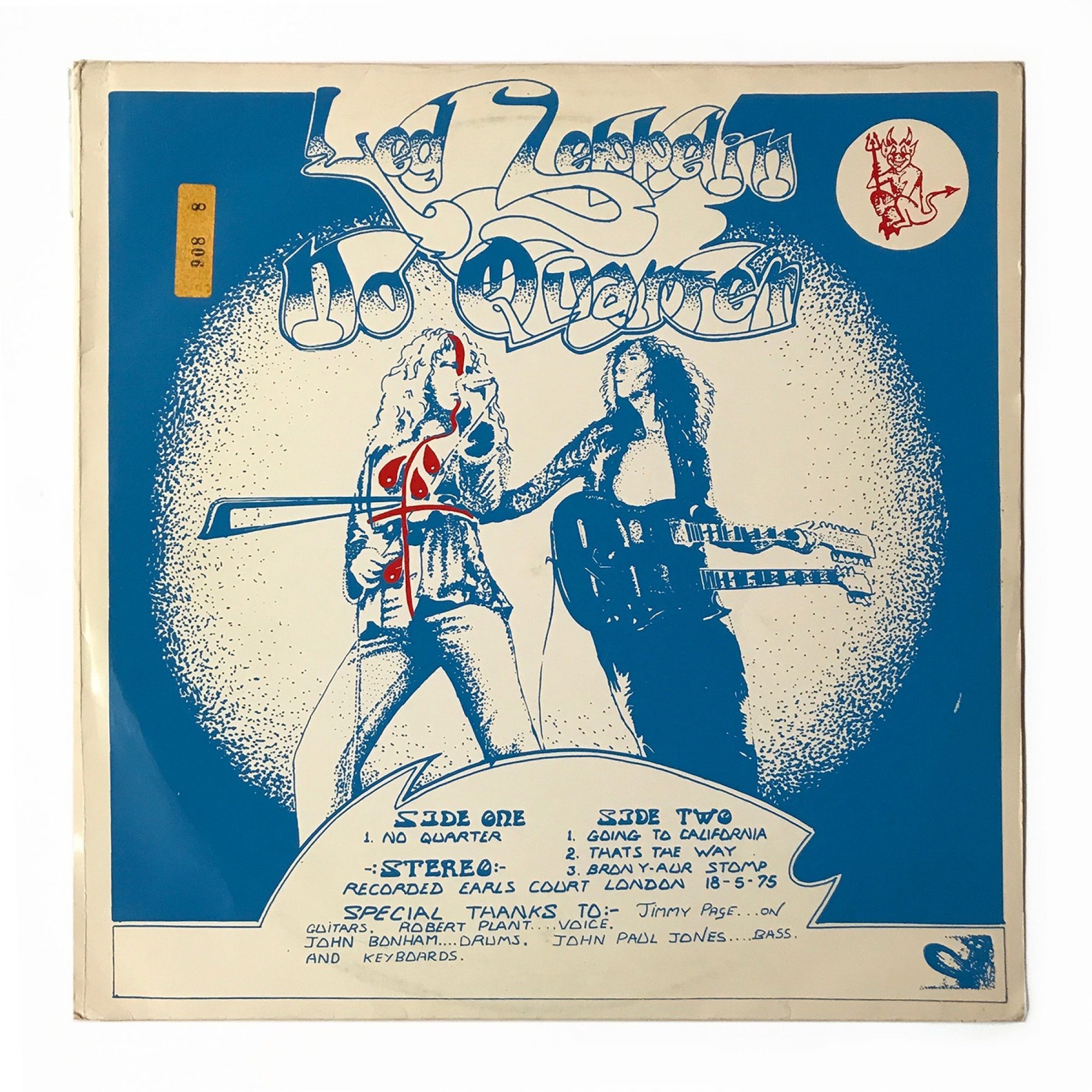

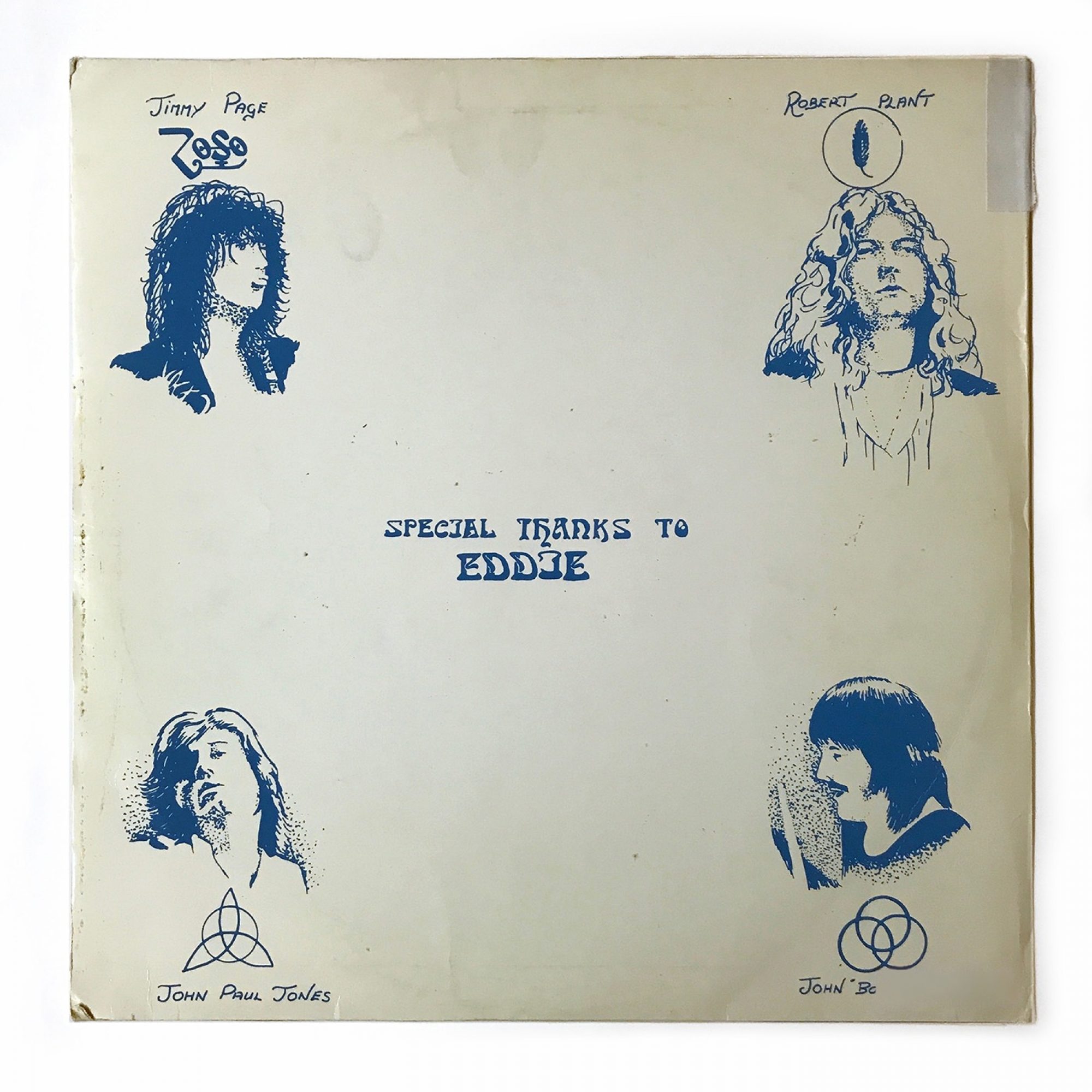

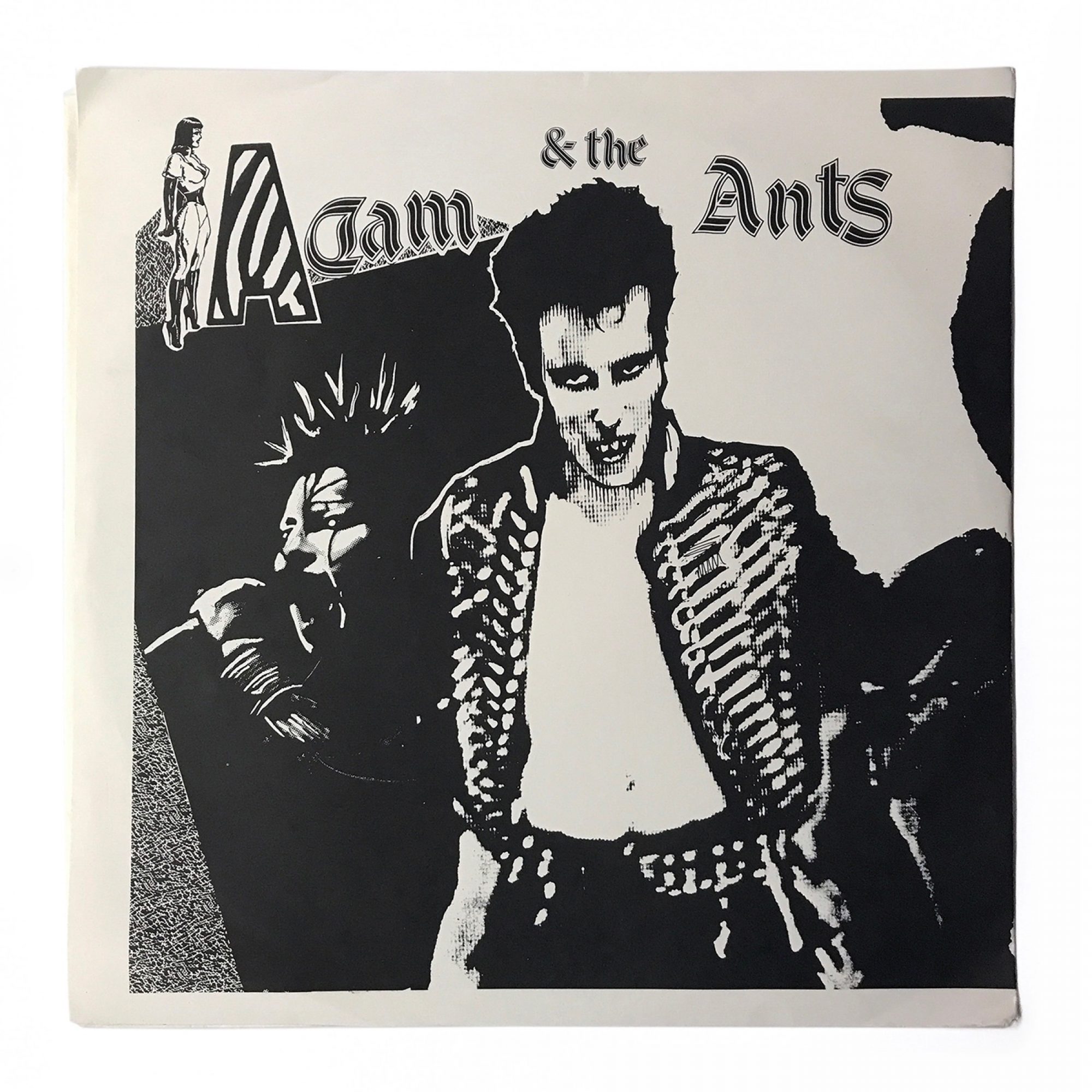

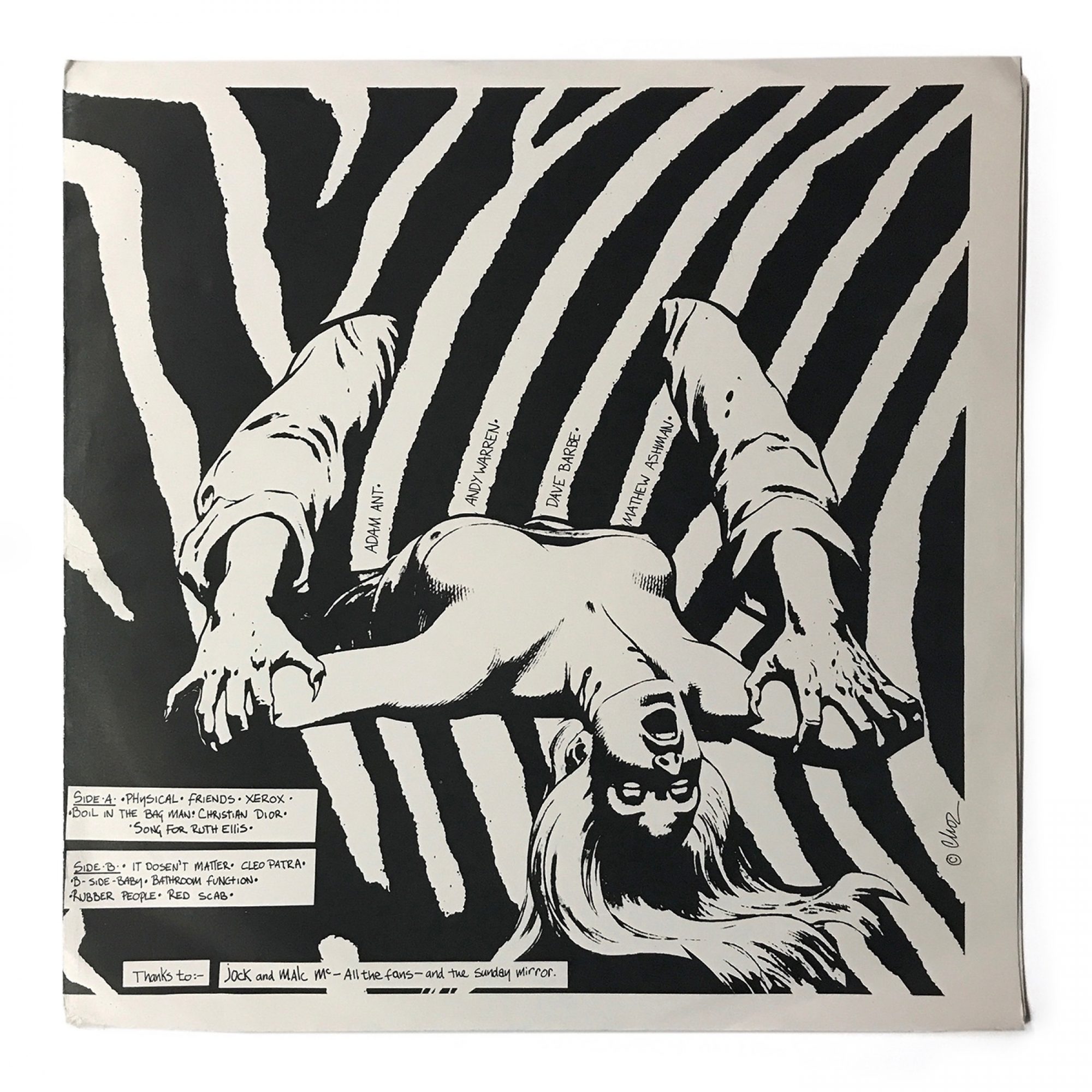

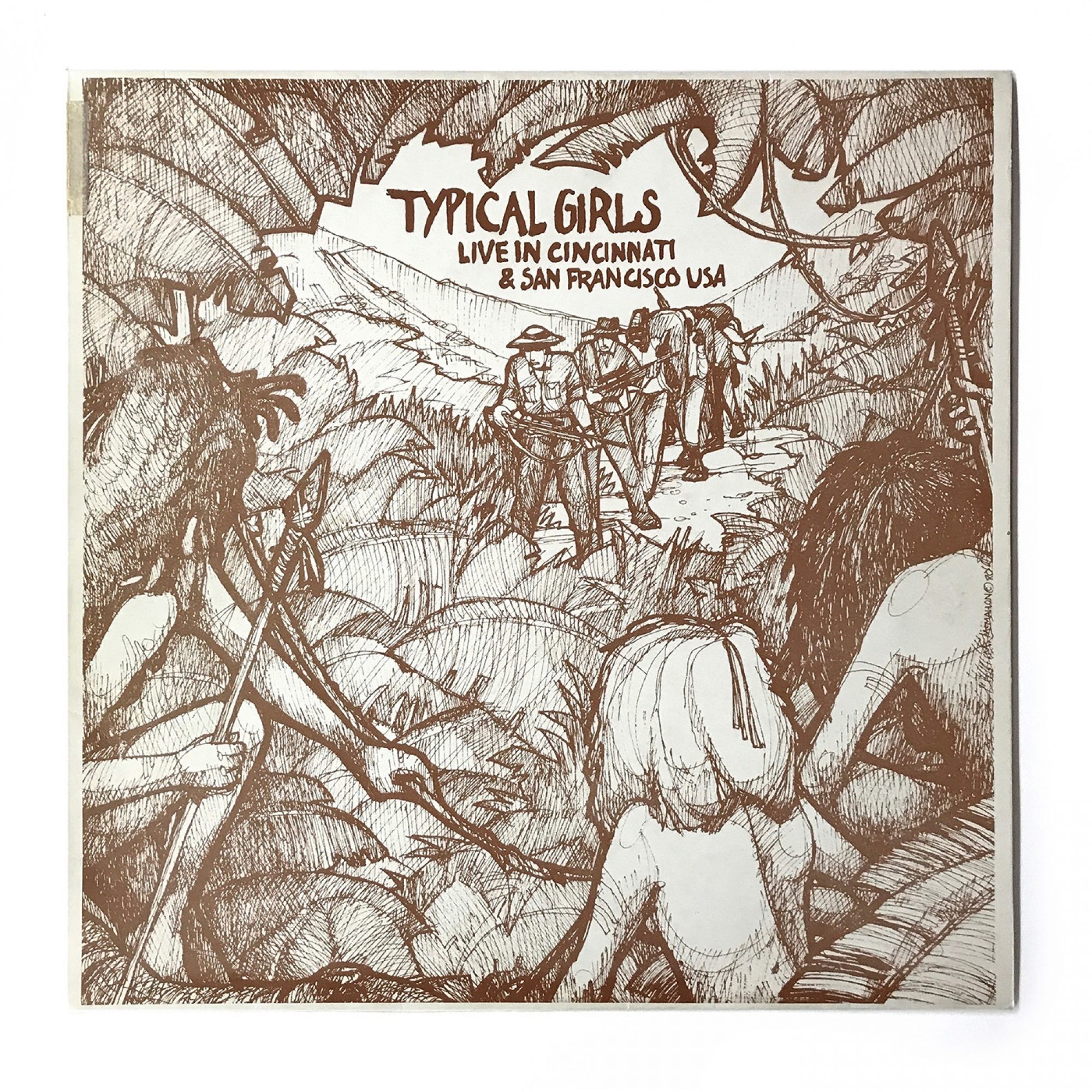

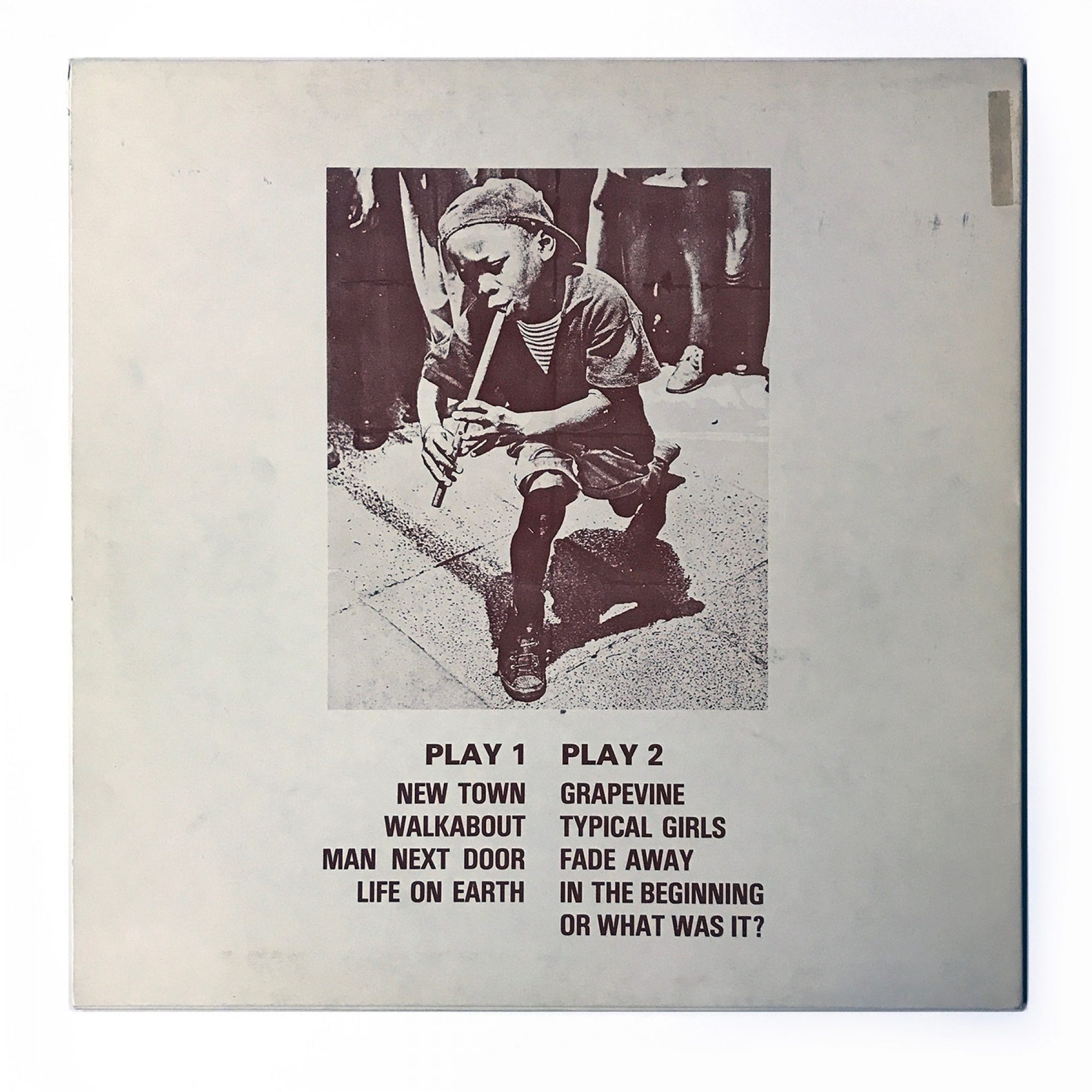

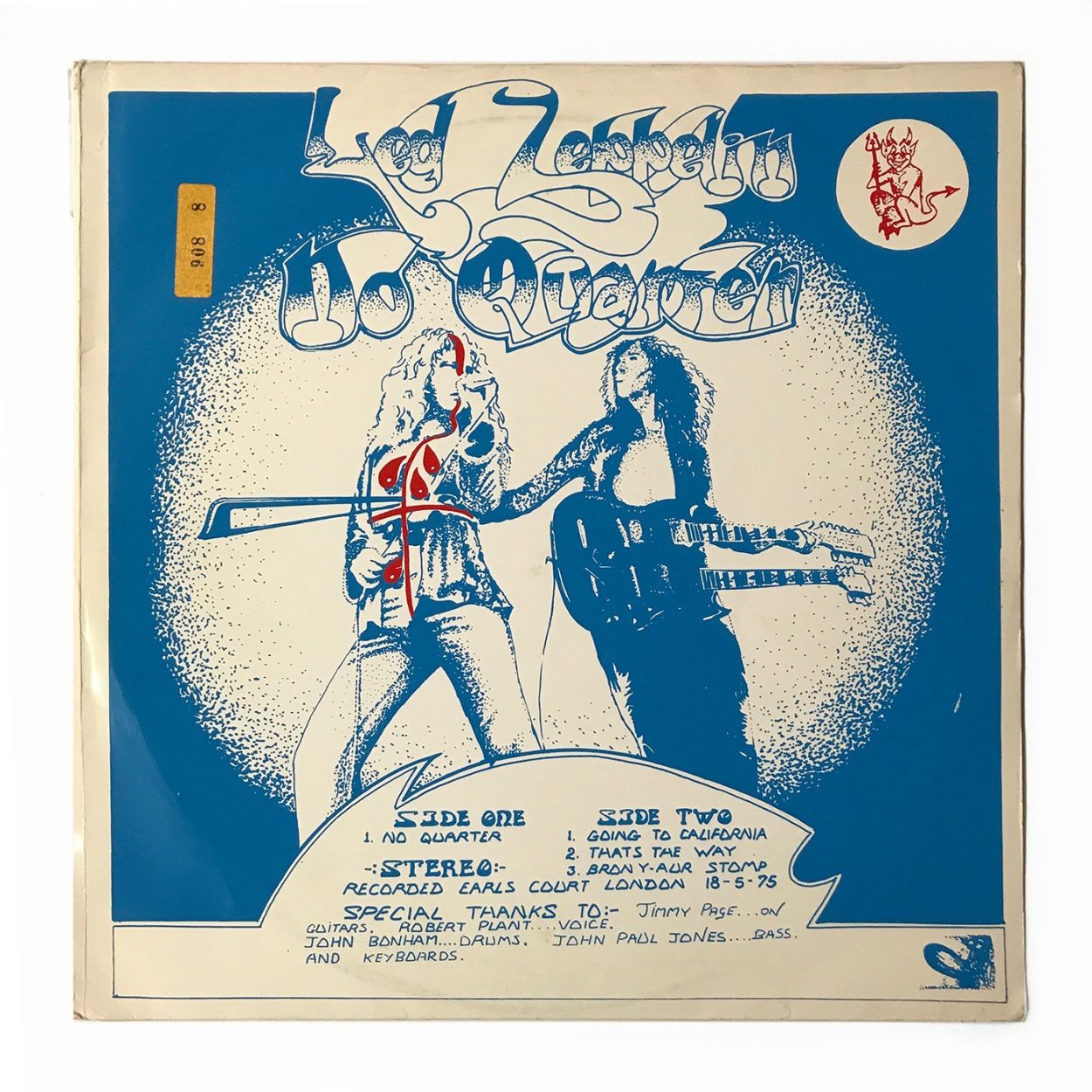

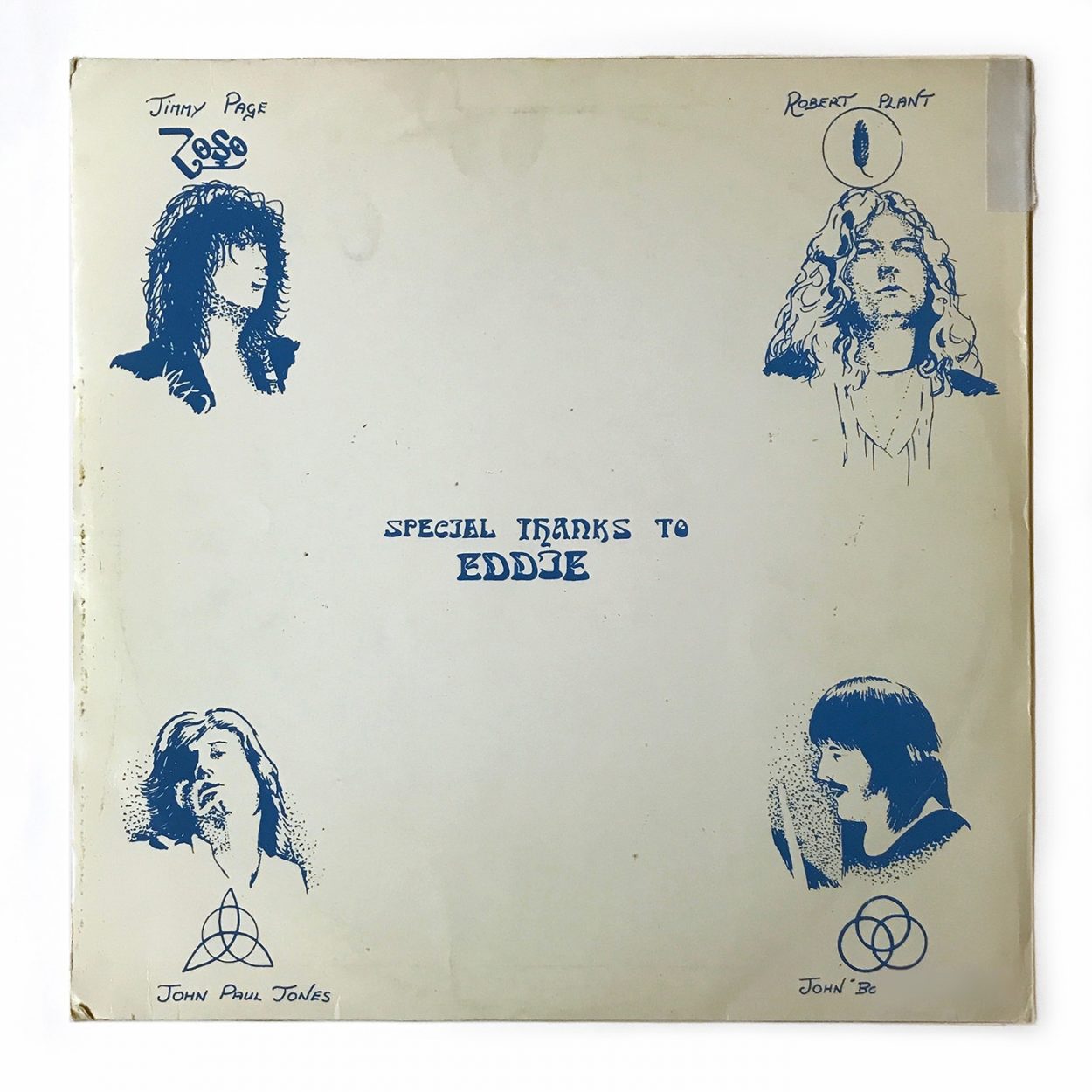

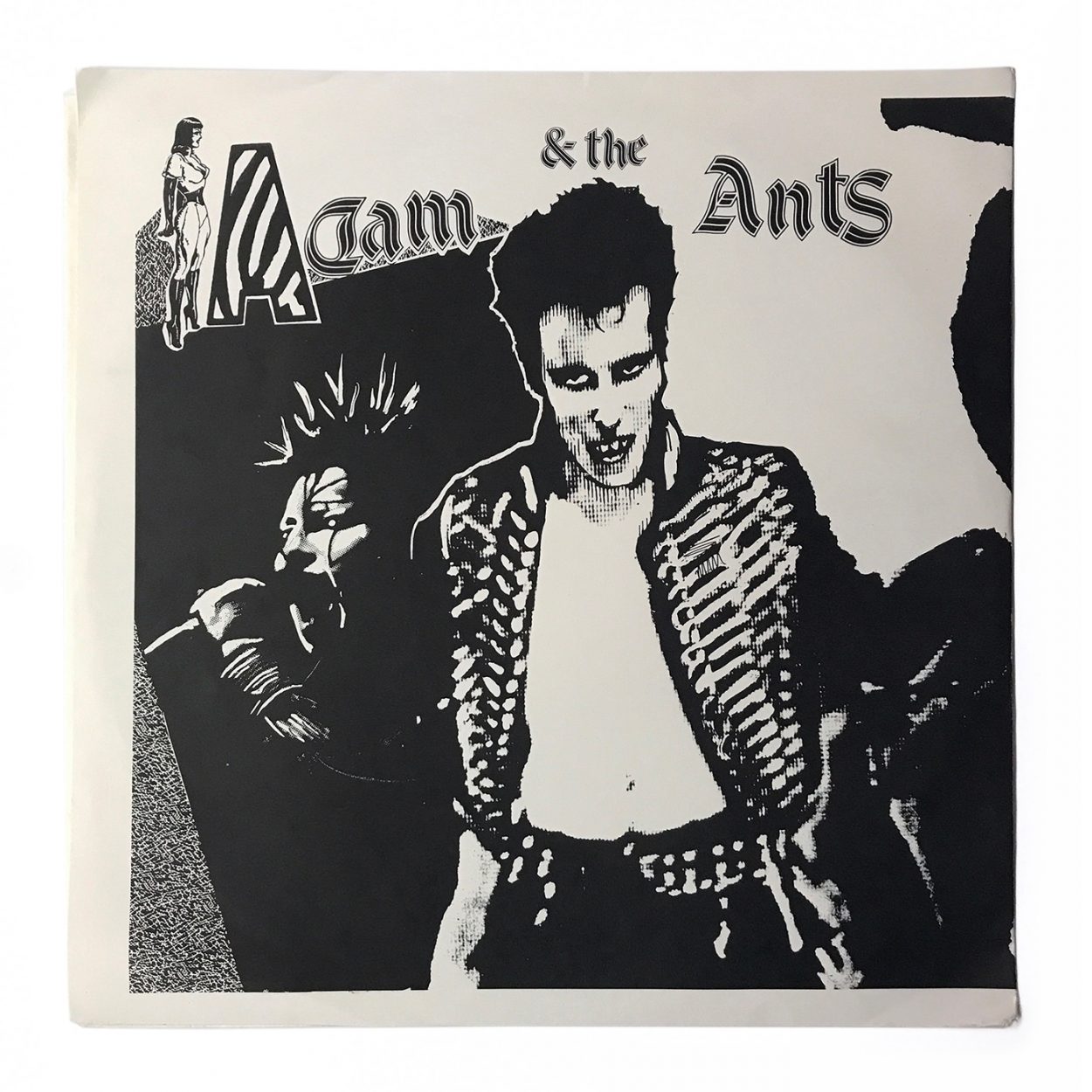

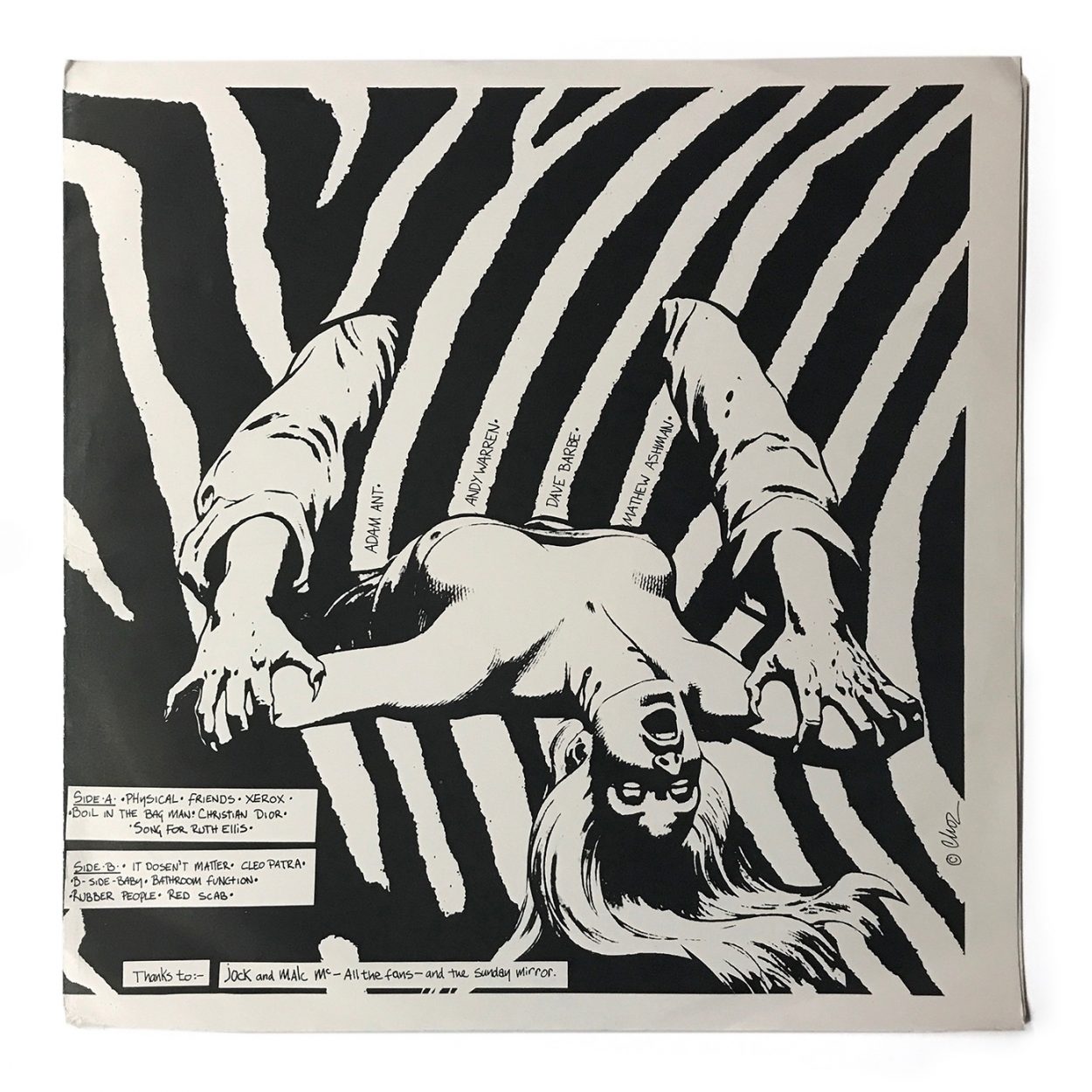

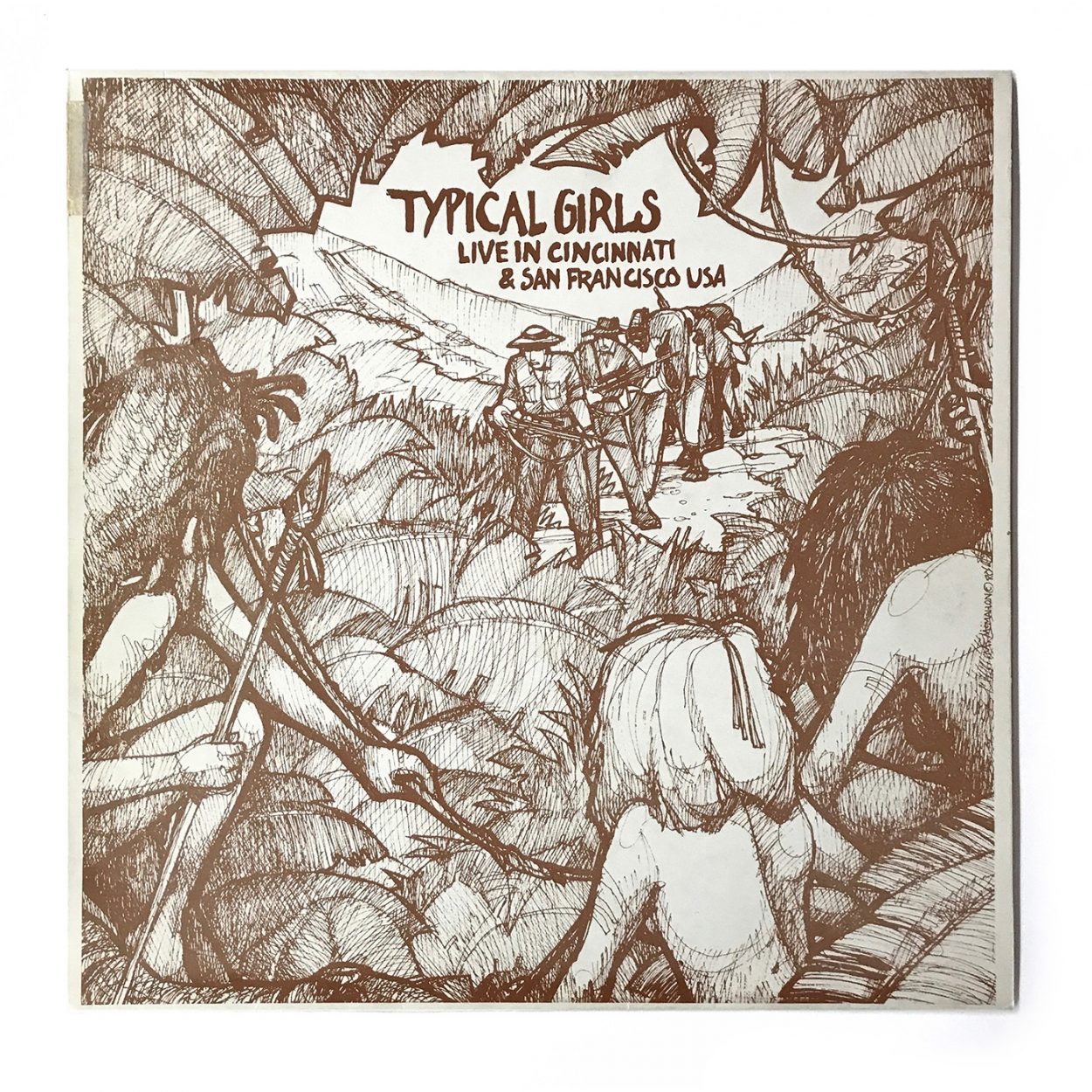

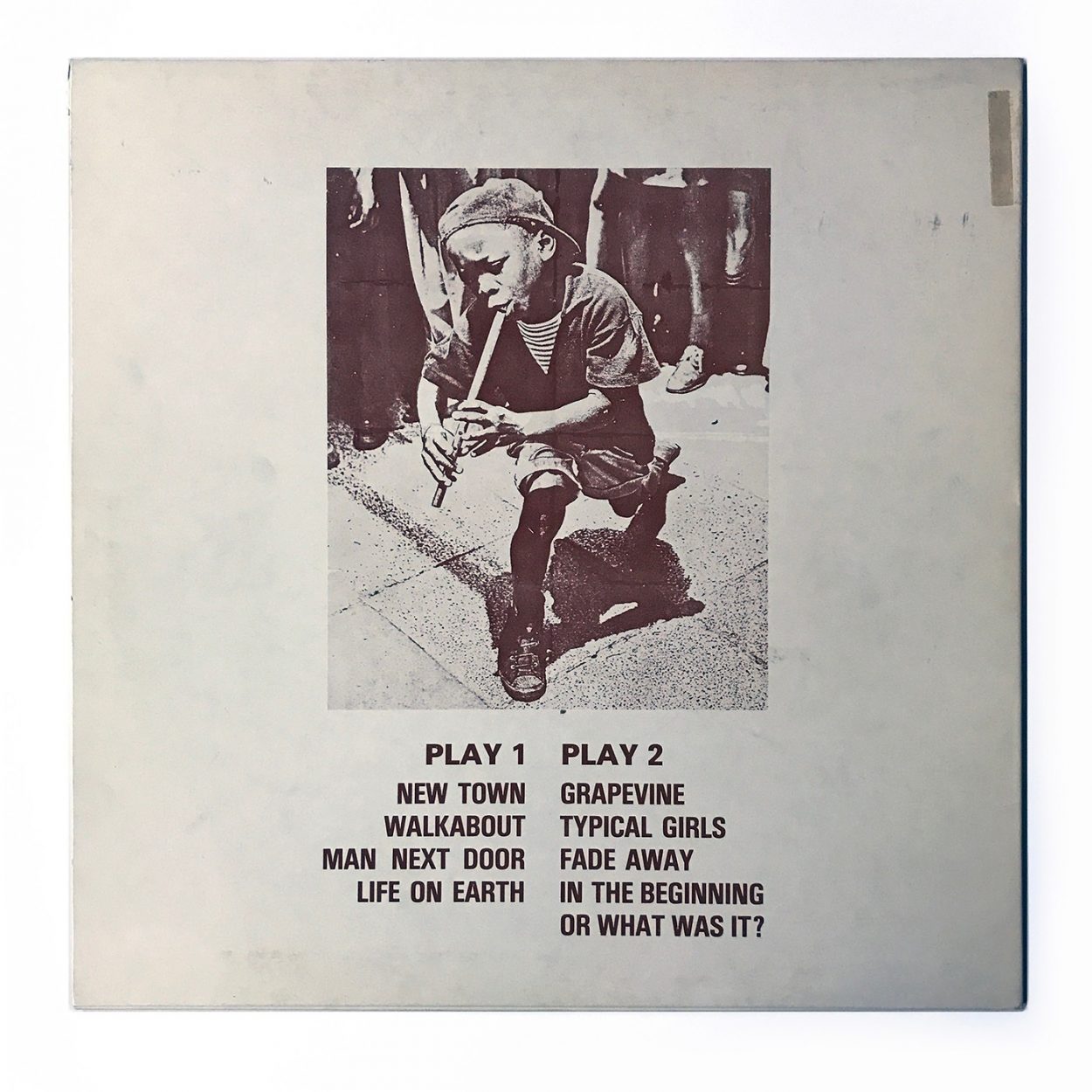

Such bootlegs are rock’n’roll relics of the pre-Internet age, perhaps only really valued now by collectors. The audio they contain, once highly prized and difficult to obtain, can mostly be found online. Yet there remains something fascinating about the vinyl bootlegs in particular, not least for the often strange and striking artwork of their covers. Some are plain white sleeves stamped with basic information, but there are clever collages, lo-fi paste-ups, hand-drawn outsider art, elaborate examples of crazy psychedelia and strange esoterica; some are ironic, witty or wildly irreverent; some are baffling, some so slick and professional, they might fool you into thinking them official.

As far back as 1929, the US magazine Variety described a growing market in ‘bootleg disc records’: actually what are now called ‘pirates’ or ‘knock offs’ - cheap counterfeit versions of officially available releases. Bootlegs proper contain material that is otherwise unavailable, either because it is out of print, or because it is unsanctioned: rehearsal recordings, demos, studio outtakes, unofficial live recordings and the like.

Although the major record labels pushed law agencies and corporate bodies like the BPI to enforce their rights, many artists at least tolerated bootlegs, and often collected them themselves. Bands like The Grateful Dead even encouraged fans to tape their concerts and while a pirate record could legitimately be said to be compromising business, bootlegs were usually bought by super fans who already owned all the official catalogue. More sympathy was due to the artists who did not want the material in the public realm - and wouldn’t profit from it - but then many recordings that first appeared on bootlegs ended up being officially released: 1969’s ‘The Great White Wonder’, a hugely popular collection of unreleased Dylan outtakes, demos and live sessions prompted the subsequent release of the ‘Basement Tapes’ series. A lucrative slew of official live albums by various bands appeared in the 70s - all capitalising on the popularity of bootlegs. (The Who’s ‘Live at Leeds’ even had a cover that masqueraded as a bootleg.)

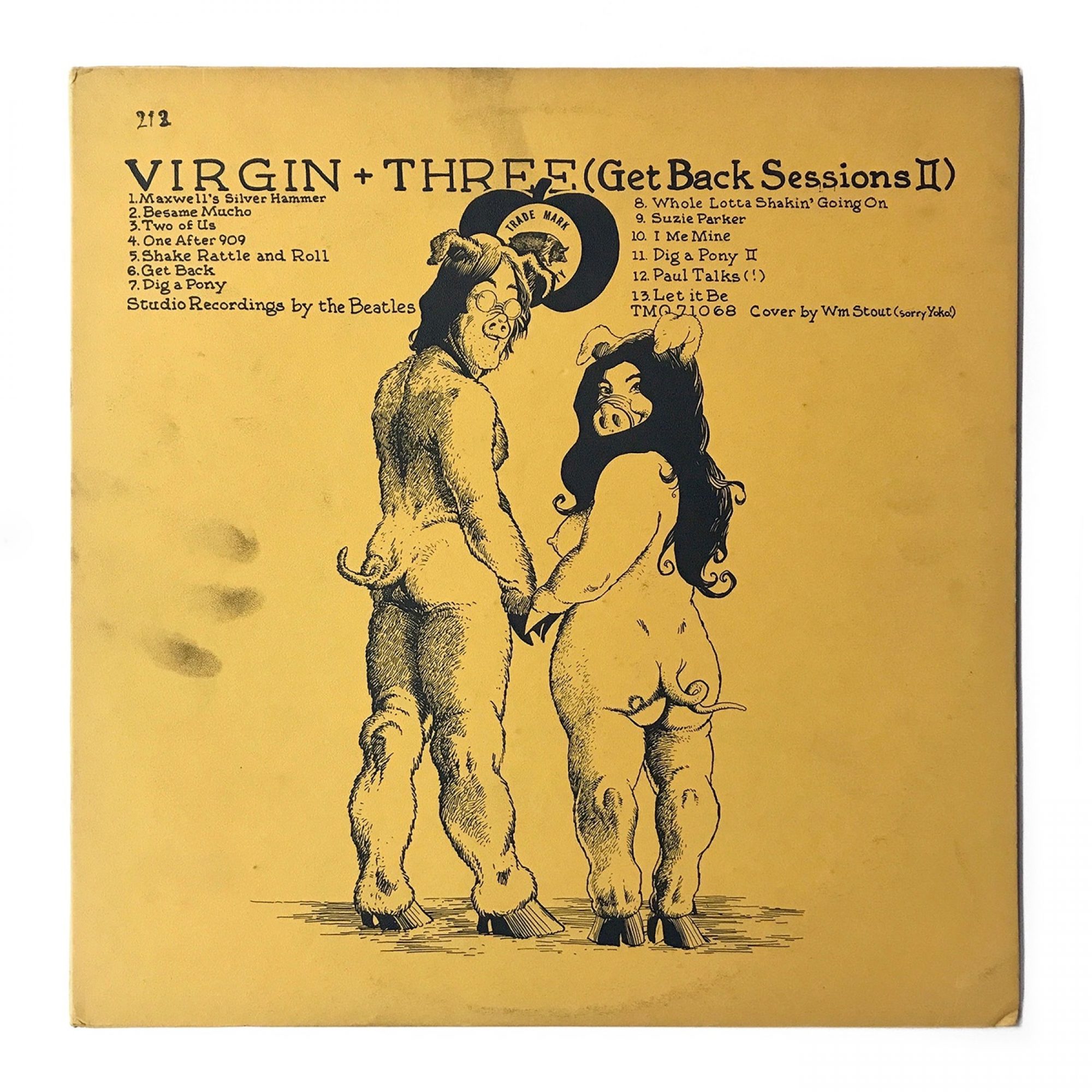

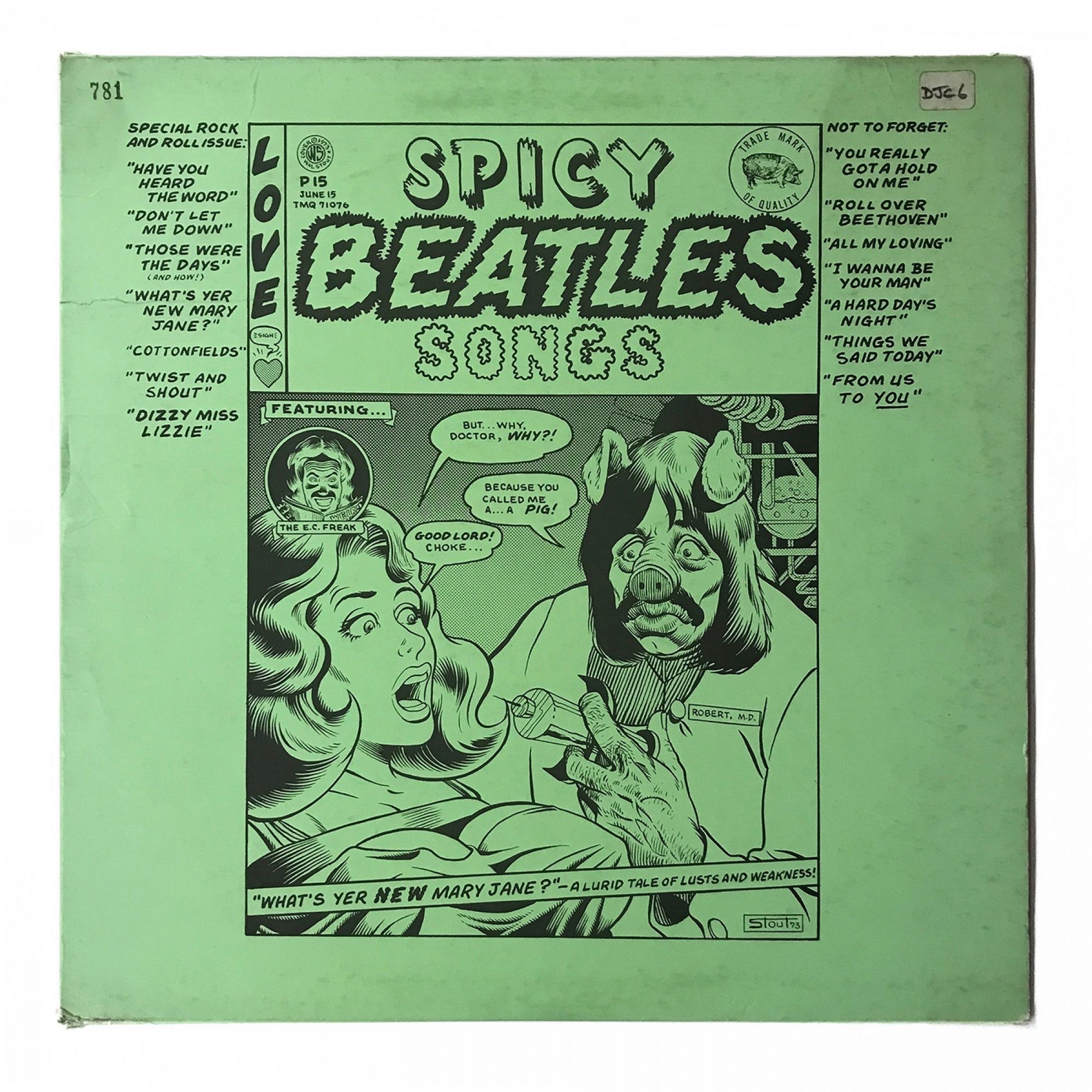

‘The Great White Wonder’ jump-started the golden age of vinyl bootlegs. It was the first release by Ken and Dub, two young and initially naive Dylan fans. It sold out so quickly, as did several subsequent pressings that they rapidly wised up to the commercial potential of a massive untapped market. Their ‘Trade Mark of Quality’ (TMQ) label and a bunch of other operators began to pump out a steady stream of concert recordings by the big rock bands of the era. TMQ’s ‘Live'r Than You'll Ever Be’, a terrific Rolling Stones live concert recording, is said to have sold over 250,000 units (enough to have earned the band a gold record) though more than half of these were probably second generation, poorer-sounding copies made by competitors.

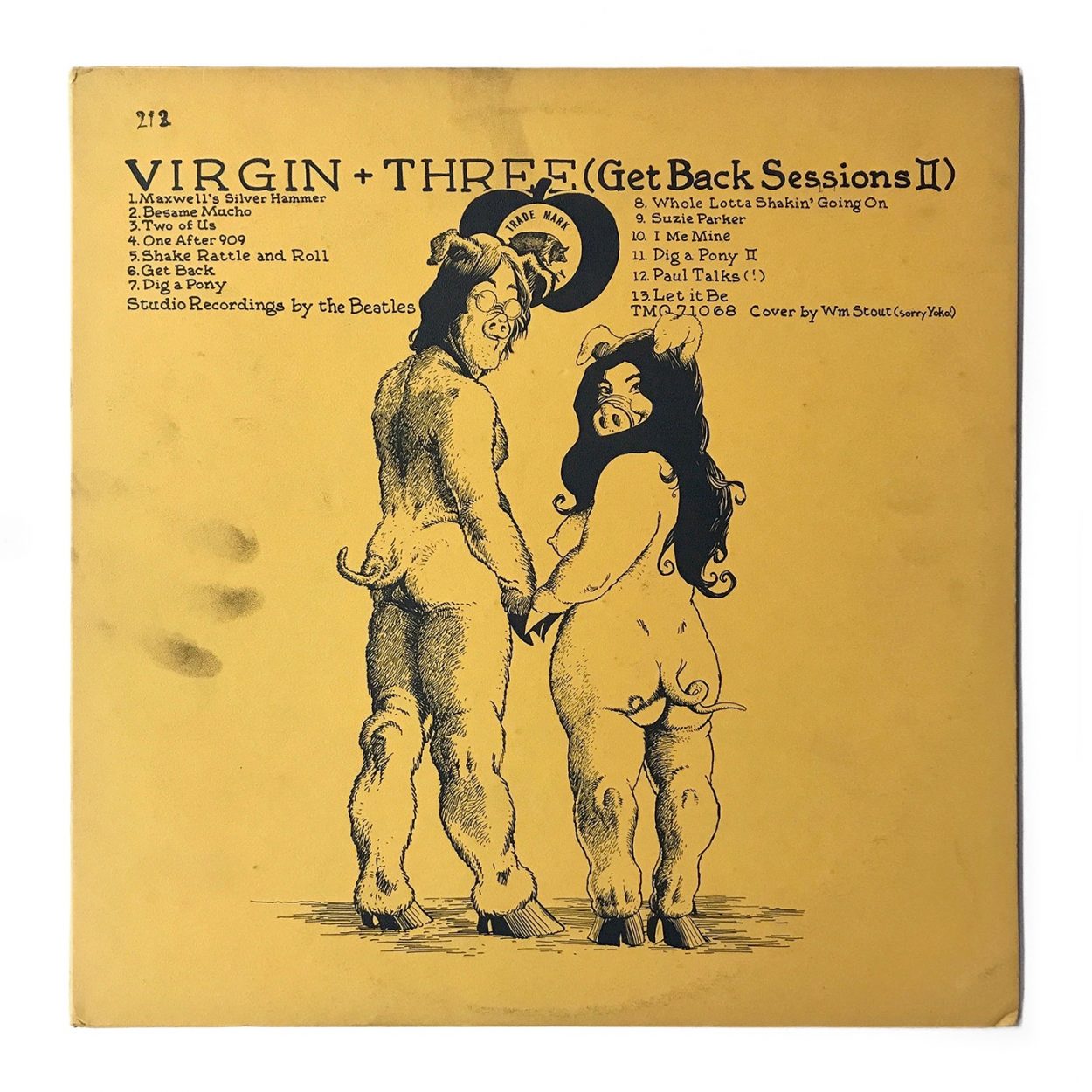

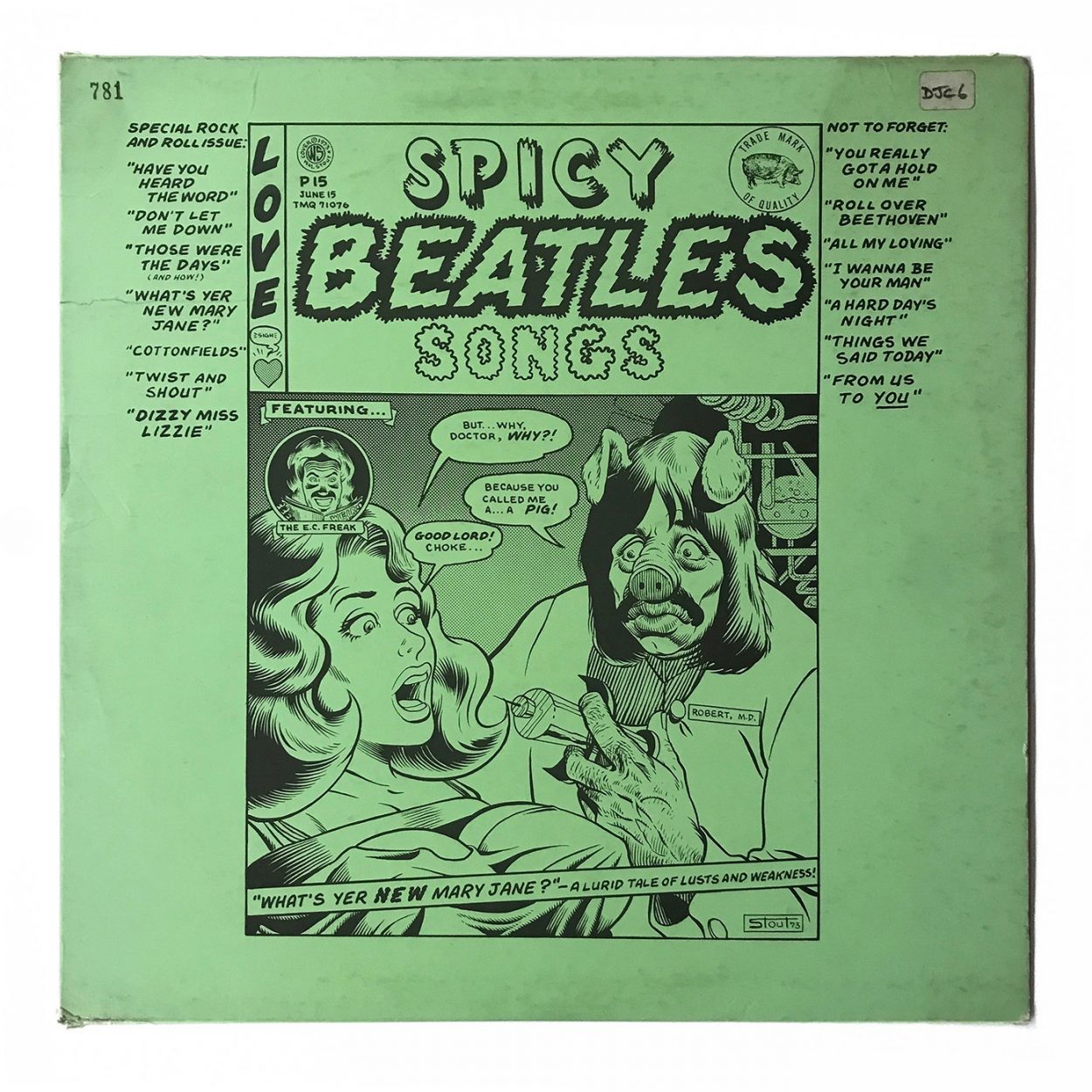

TMQ productions were often excellent and the way they were packaged began to play an important part in the branding of the label. A chance meeting in a record store led to many of their releases having covers designed by illustrator William Stout, who became the pre-eminent bootleg artist of all time. His idiosyncratic covers became a way of distinguishing the label’s authenticity, although of course they too were copied and ripped off.

Stout mixed Robert Crumb-esque pen drawings with ribald caricatures of band members, surreal captions, comic layouts, visual puns - and pigs. His obsession with porcine motifs gave TMQ an identity far more recognisable than that of their competitors - his irreverent take-off of the album cover of John and Yoko’s ‘Two Virgins’ for the artwork of TMQ’s ‘Beatles Get Back II’ bootleg is a classic.

“I used to knock them out because I was only being paid fifty bucks per cover. Then, I asked myself, ‘If you’re not doing them for the money, then why are you doing them?’ I took a completely new attitude and approach and decided that, regardless of what I was being paid, I was going to do my best work.”

And he did. Stout went on to become a successful graphic artist working in film and publishing and remains rare in being known – and lauded - for his bootleg covers. Most of those who created the artwork for illicit records understandably stayed discreetly anonymous.

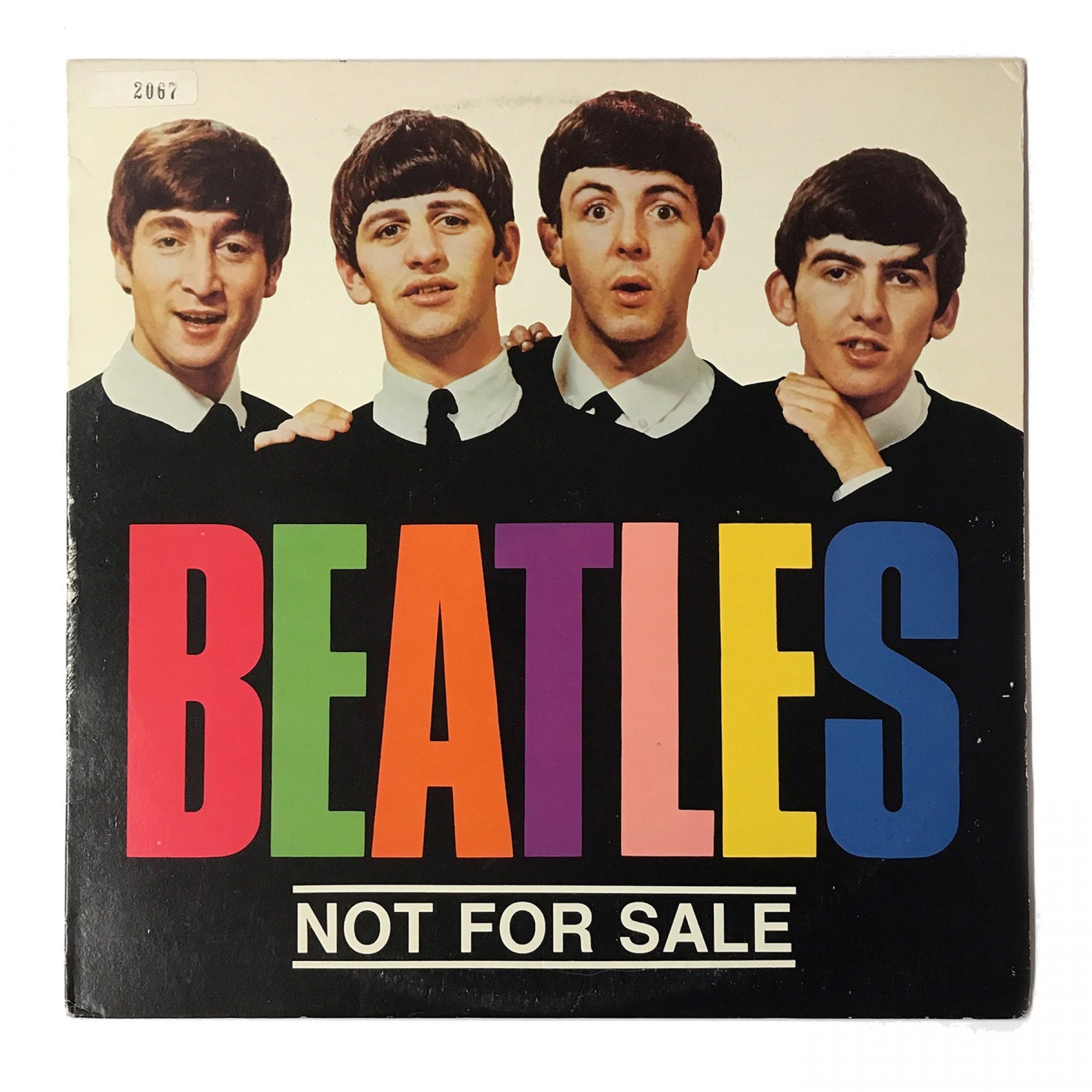

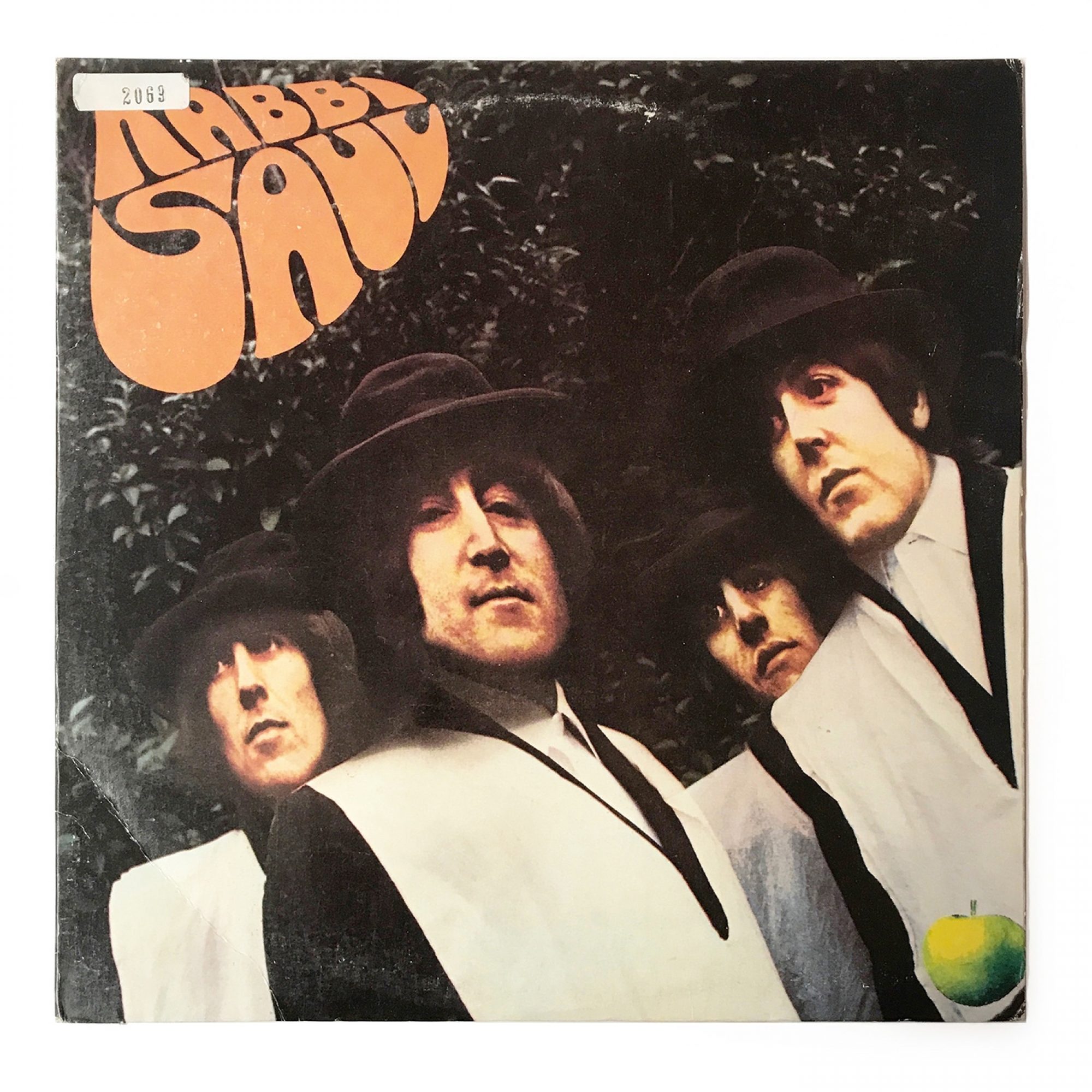

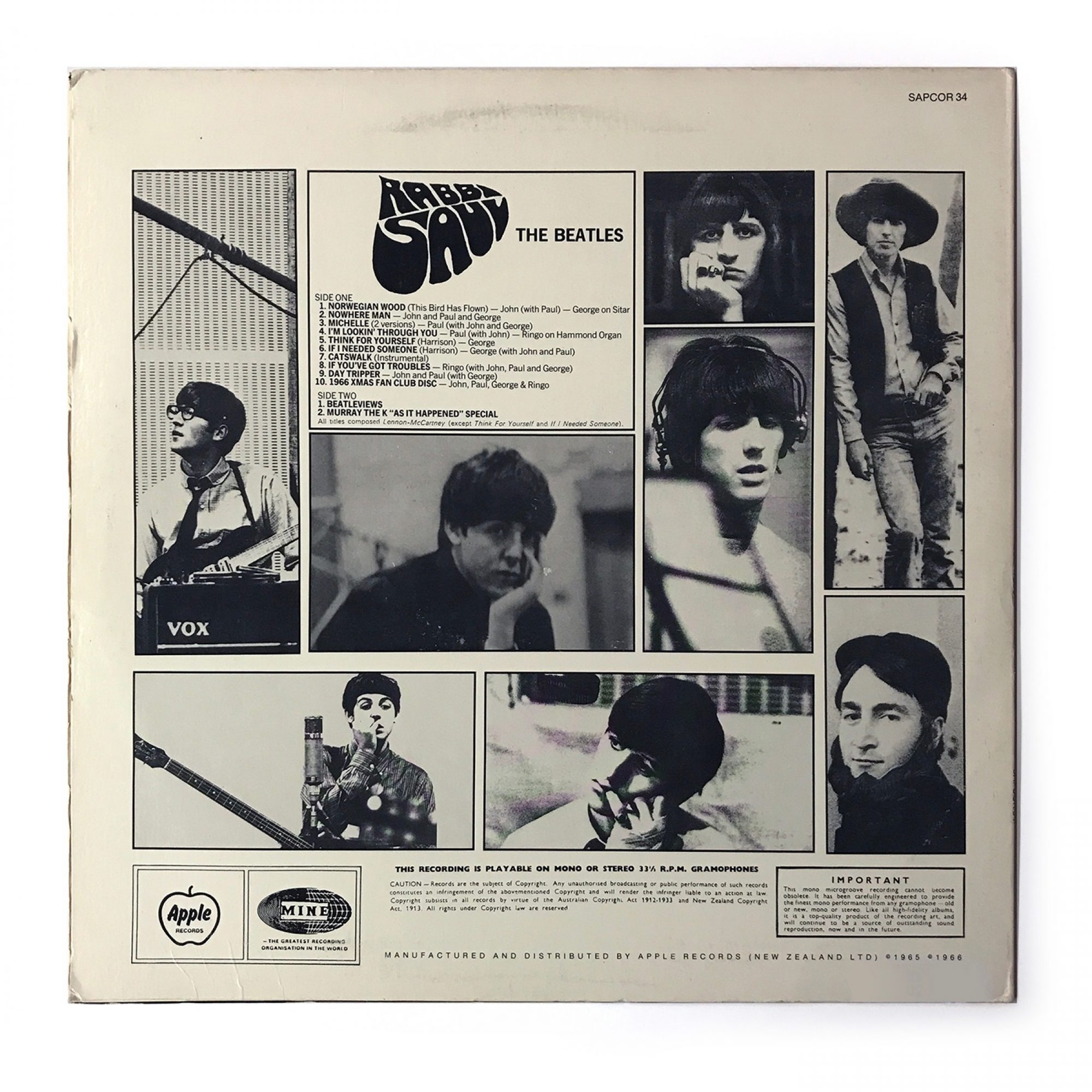

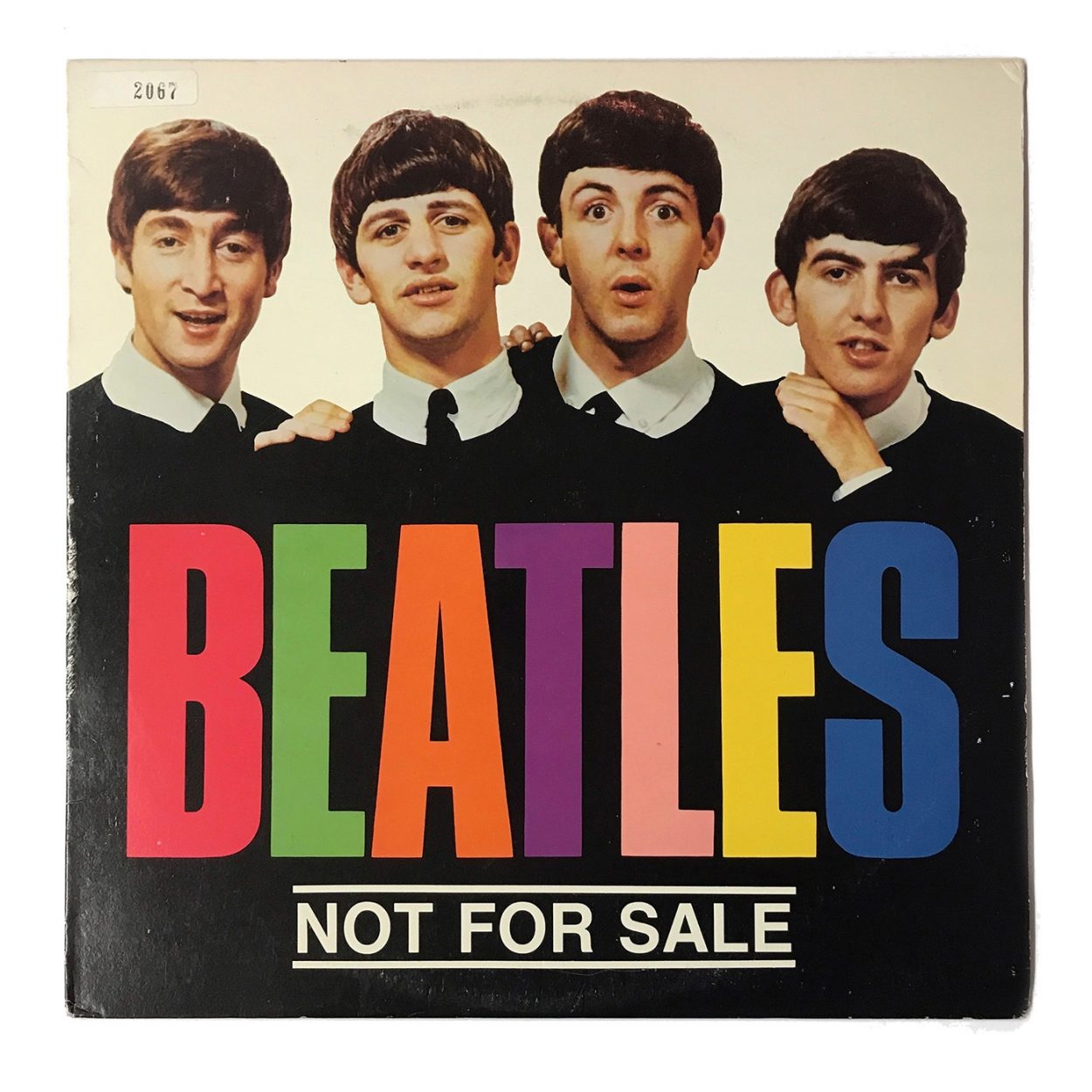

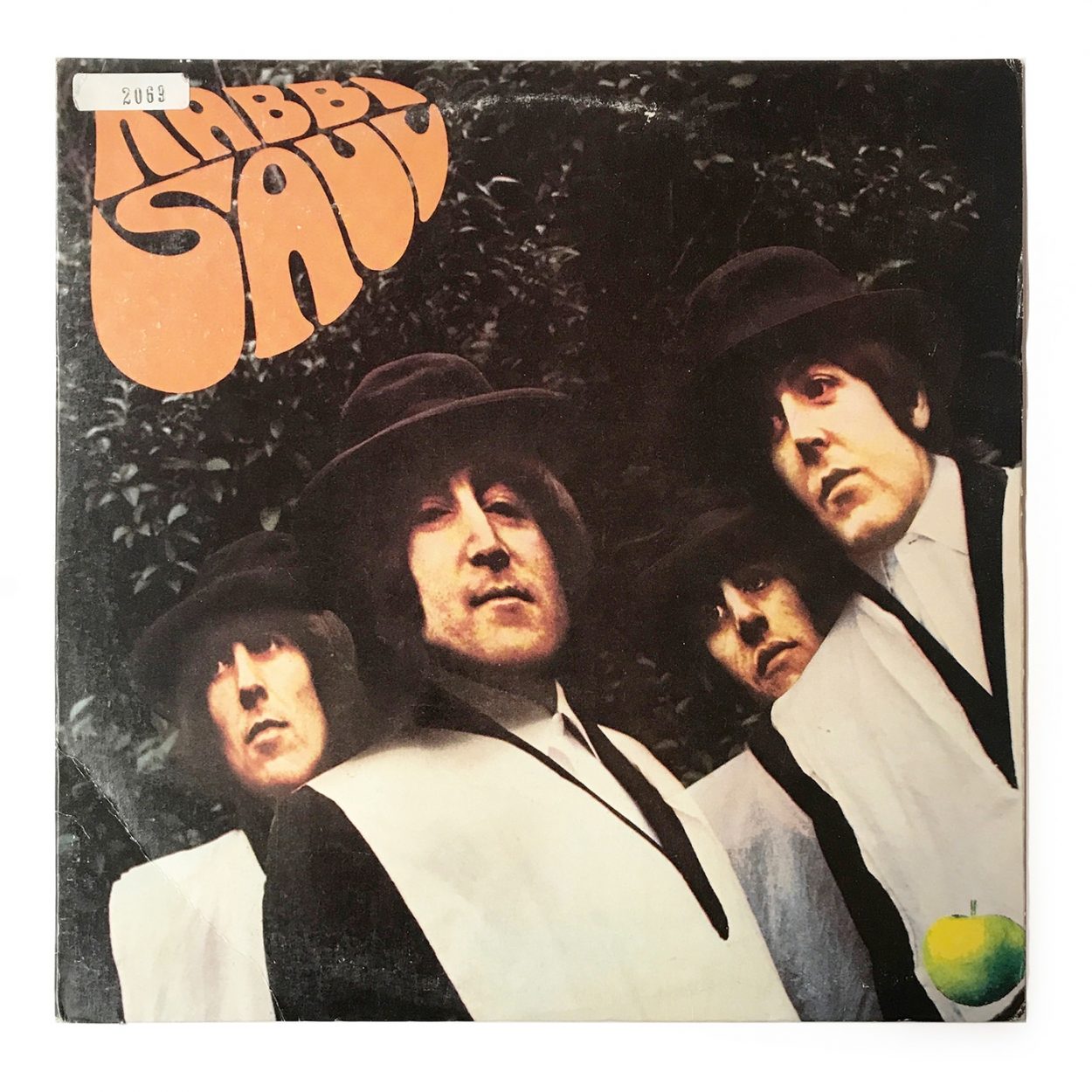

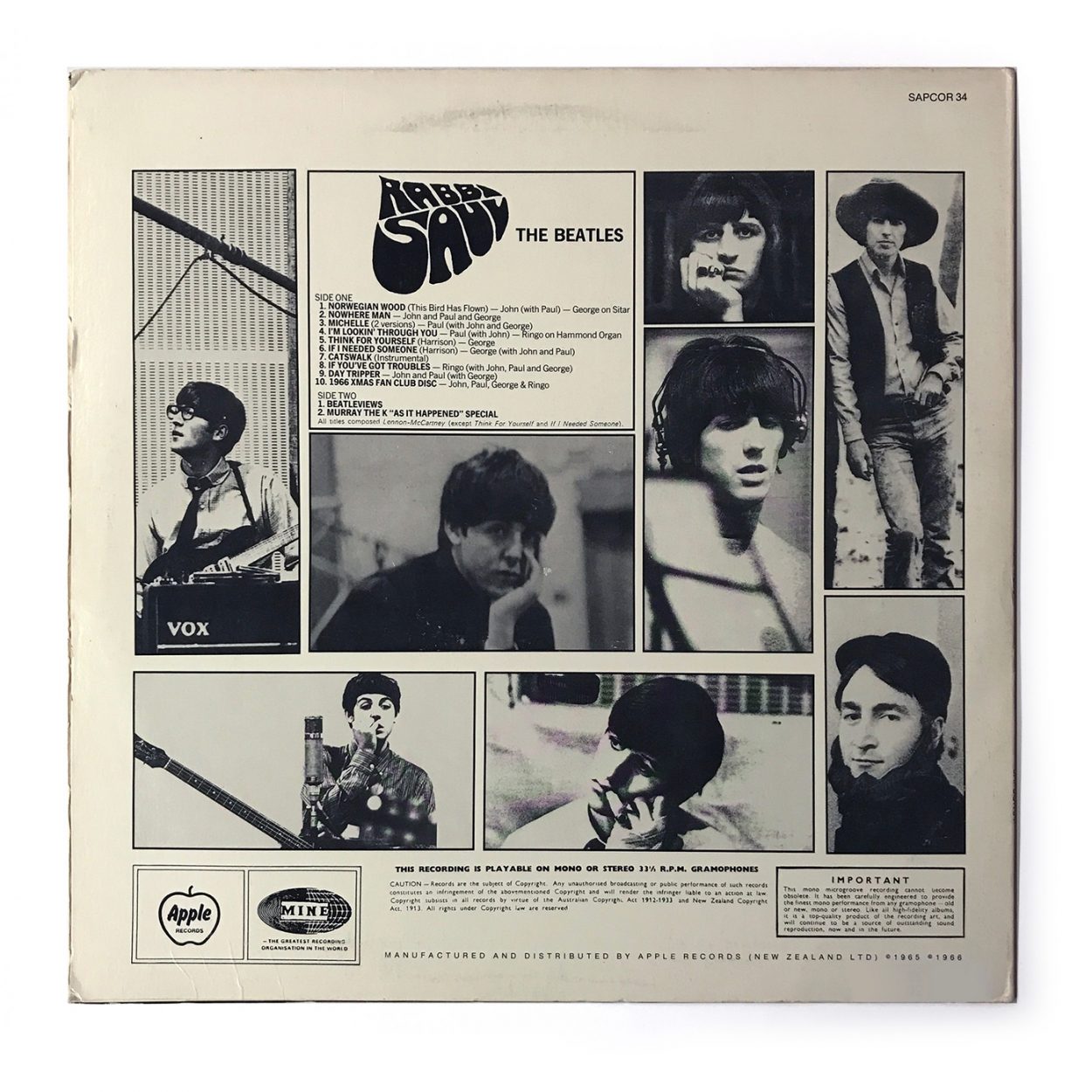

Although The Beatles had long split, their recordings continued to be bootlegged during the 70s and beyond. 1985’s cheeky ‘Beatles Not For Sale’ sleeve, a wry take-off of the official 1964 ‘Beatles For Sale’ could fool punters into thinking it official. The cover of ‘Rabbi Saul’, 1988, augmented the Fab Four from ‘Rubber Soul’ with Jewish outfits – for no apparent reason apart from the punning fun of it.

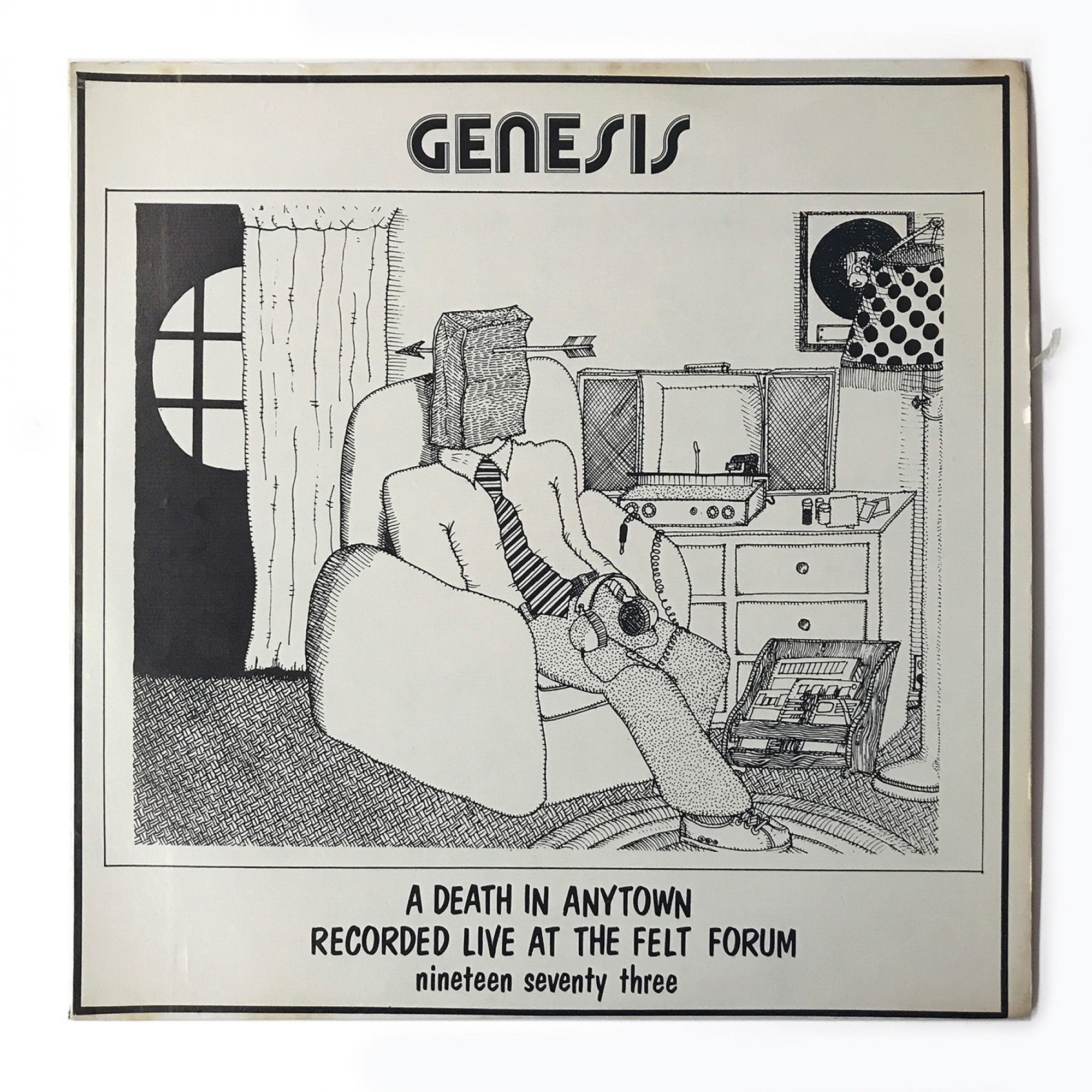

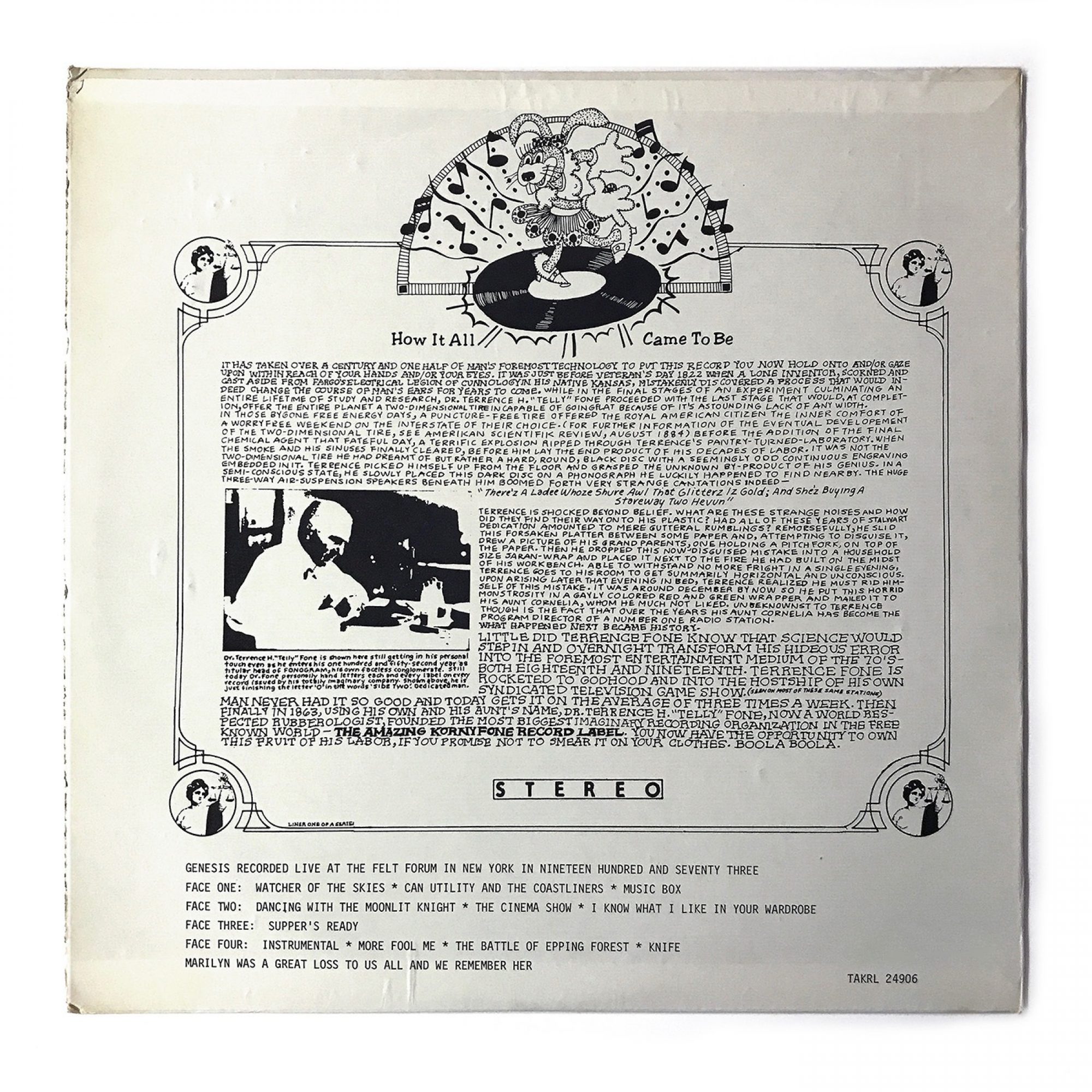

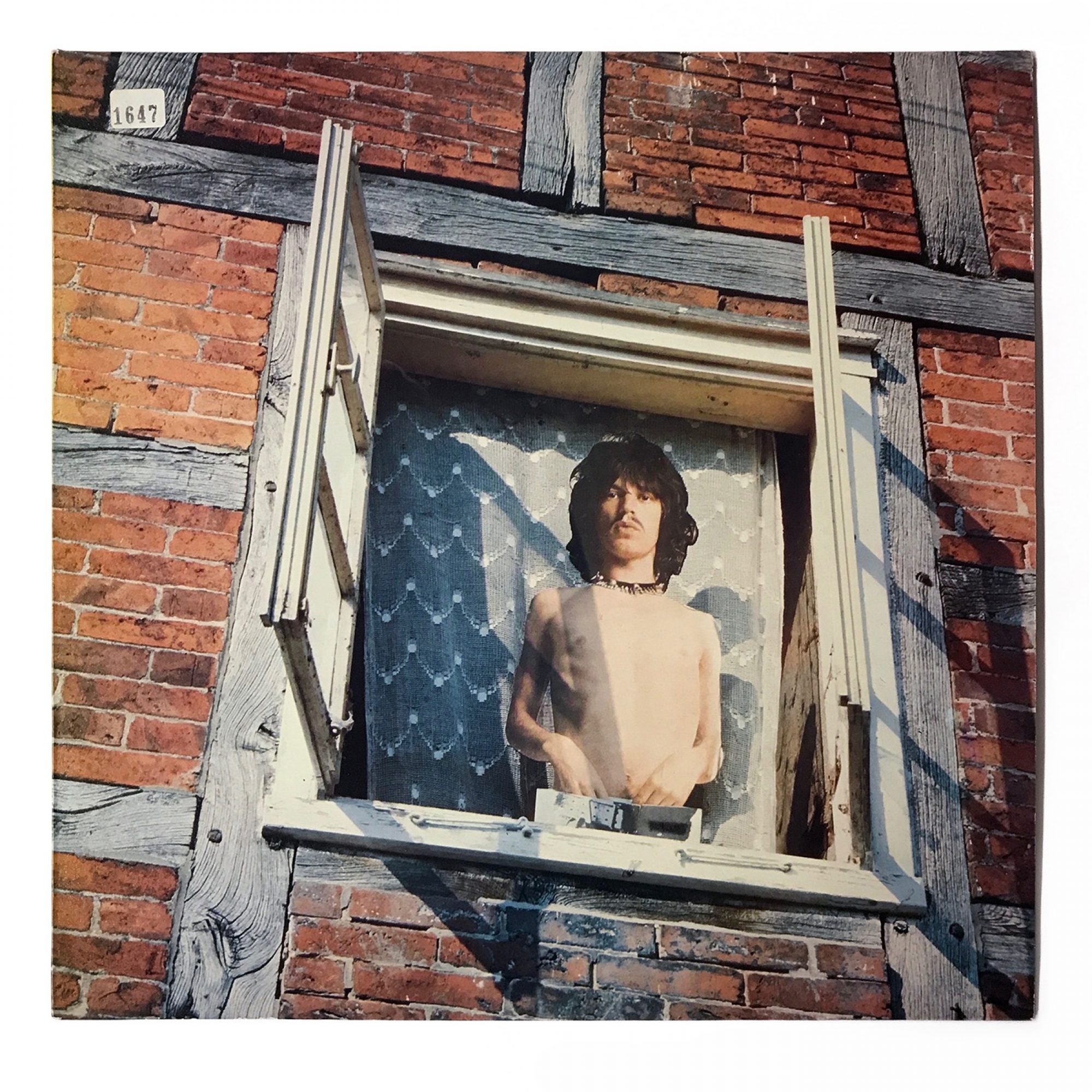

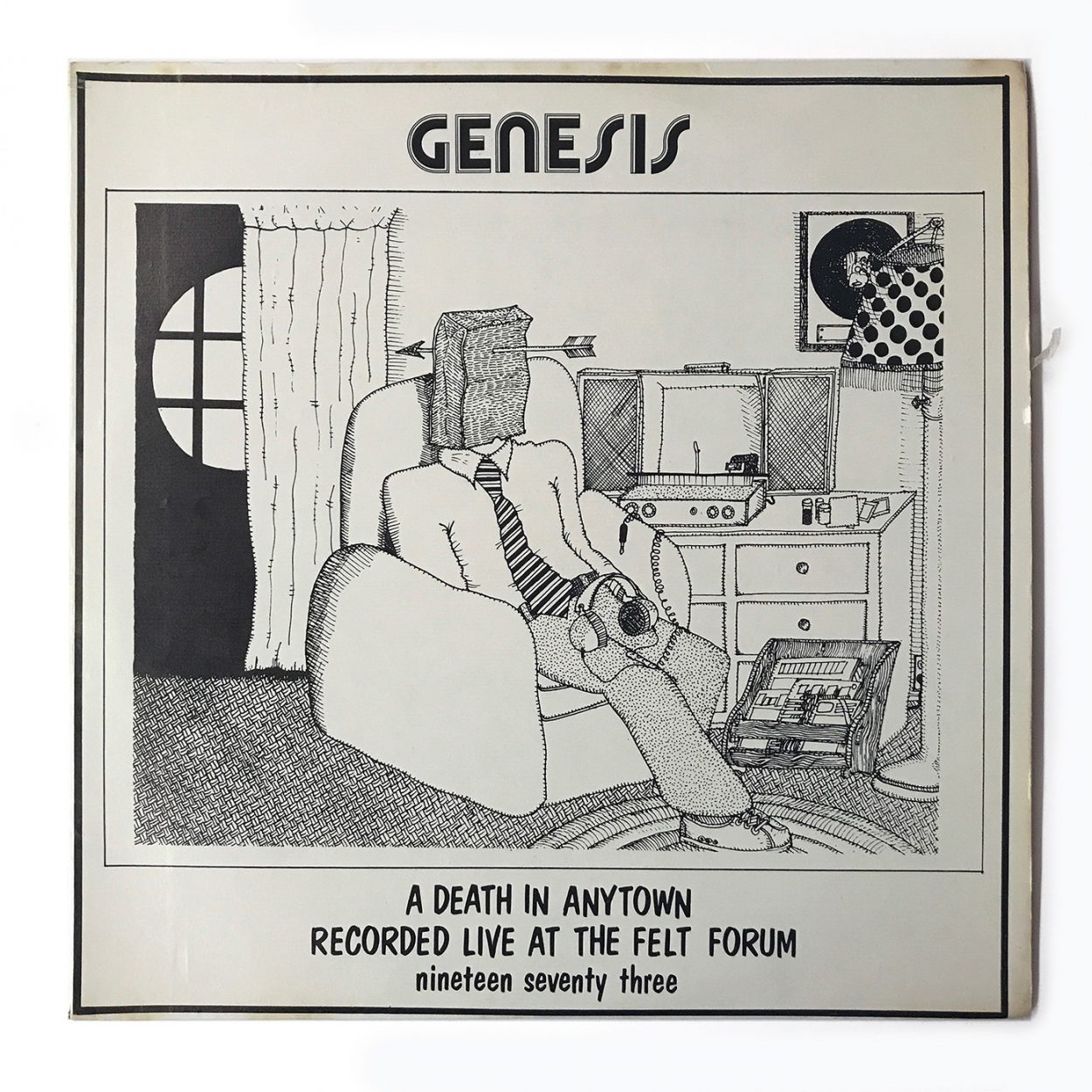

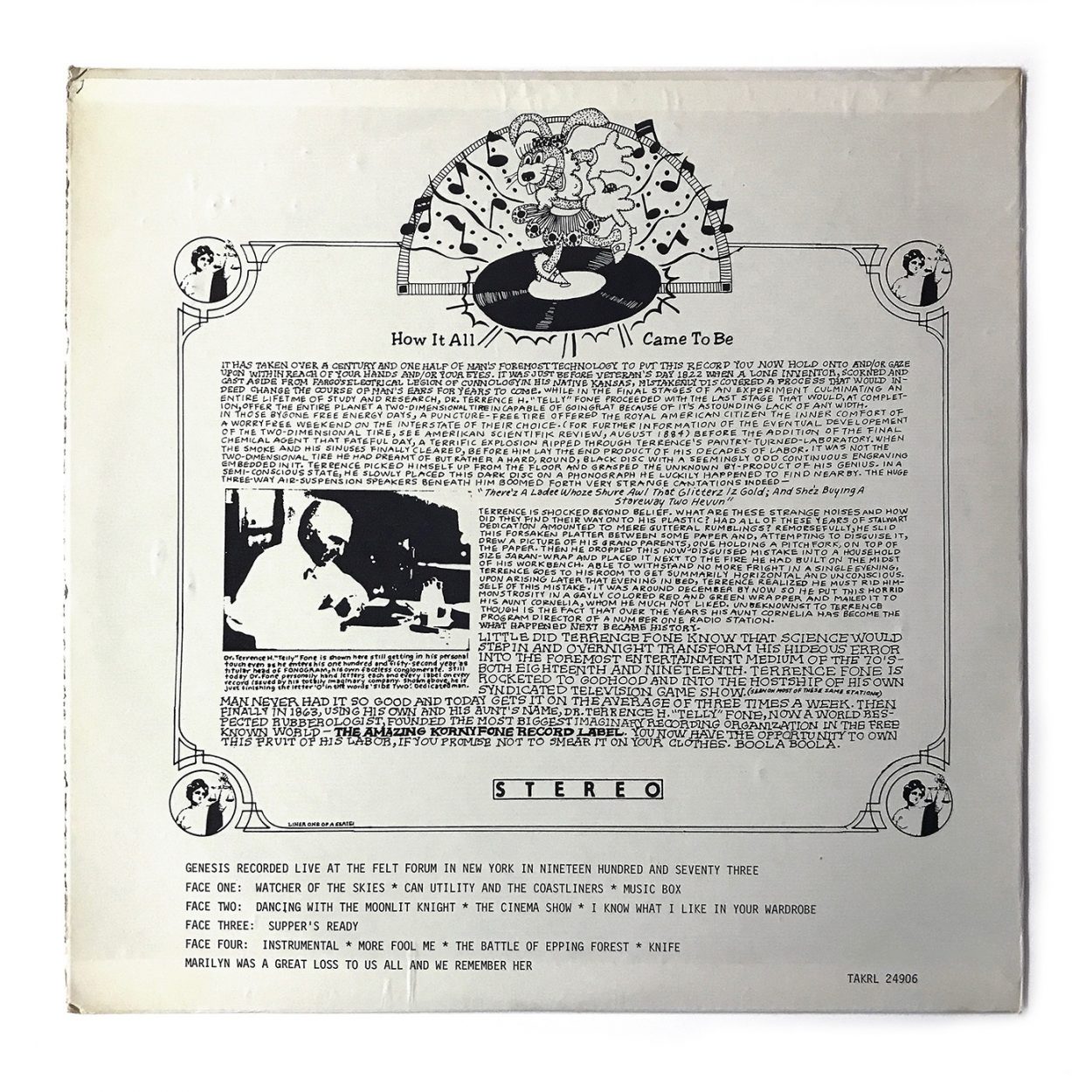

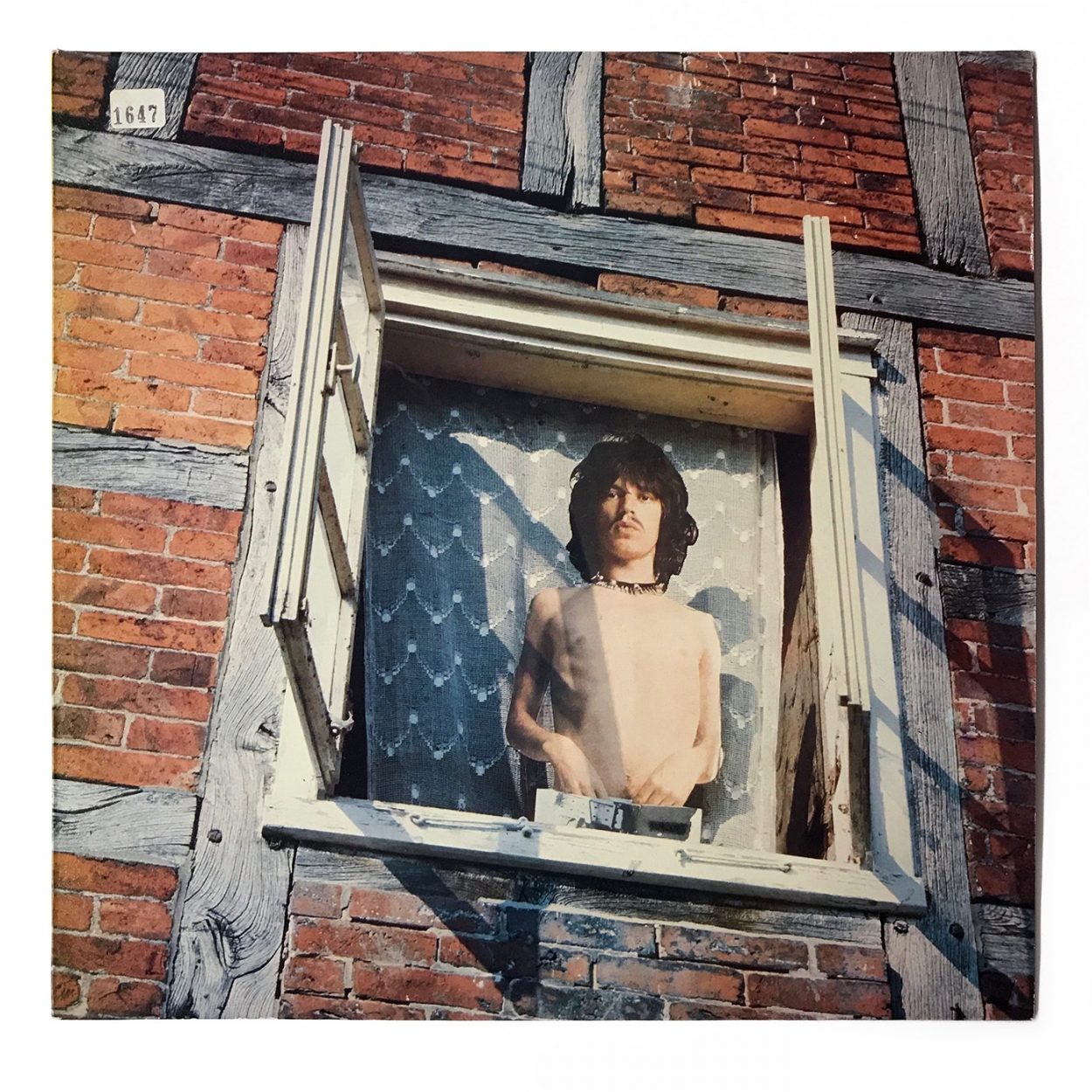

Irreverence was often the order of the day when it came to bootlegs of the big prog. rock bands who often took themselves as seriously as their fans did, a mystique maintained by their record labels – and one the anti-establishment bootleg artists enjoyed puncturing: the cover of Genesis’s ‘A Death In Anytown’, a 1973 live concert, features a man wearing a paper bag on his head with an arrow through it and an elaborate lampoon on the history of vinyl recording on the back. The Led Zeppelin ‘No Quarter’ bootleg released in 1975 by the British label Red Devil, shows Jimmy Page sawing Robert Plant in half with his violin bow - along with some very pretty fan art of the band on the rear. The Rolling Stones ‘The Stars in the Sky That Never Lie’, a recording of a 1973 German show, features a cardboard cut-out of a naked Mick Jagger leering out of a country house window.

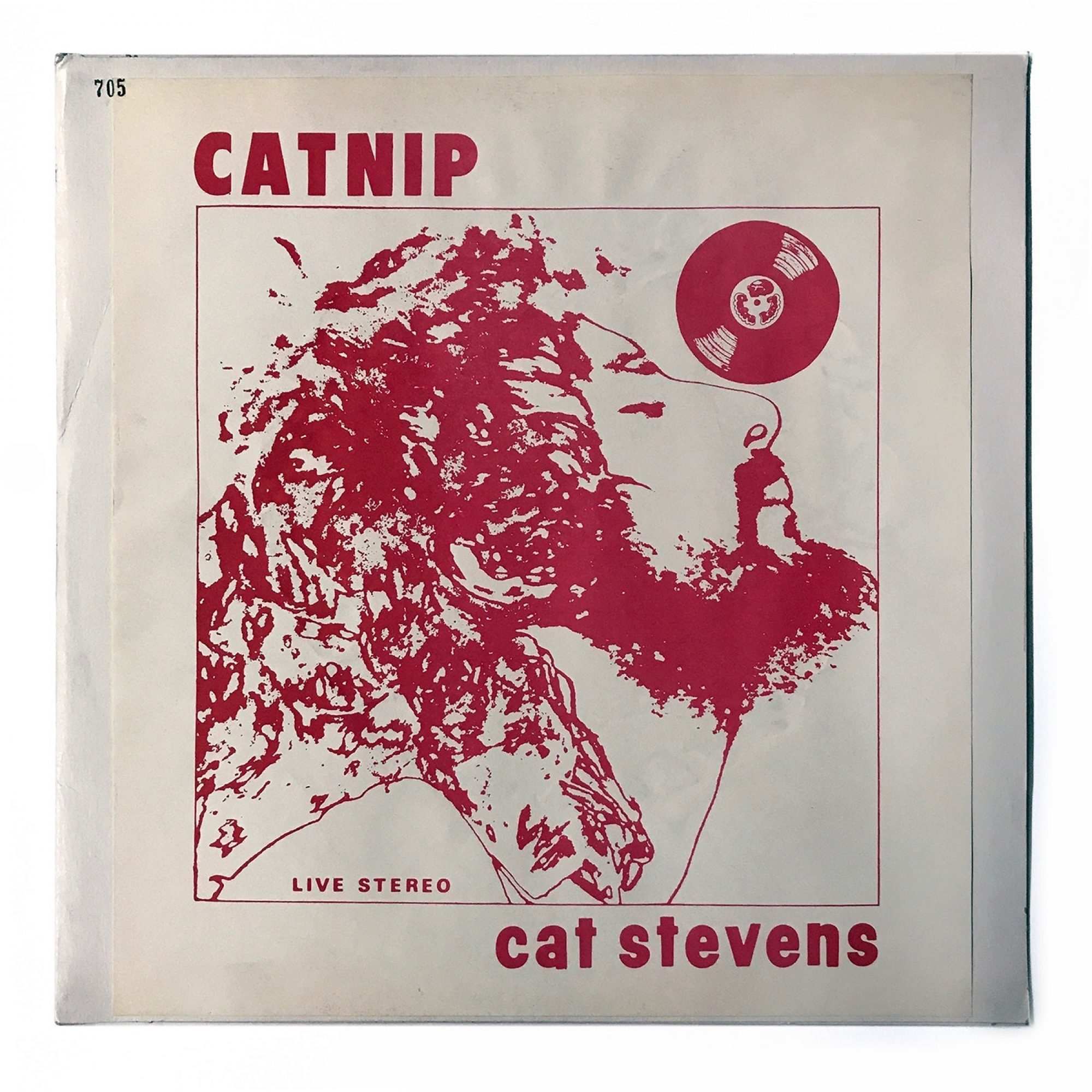

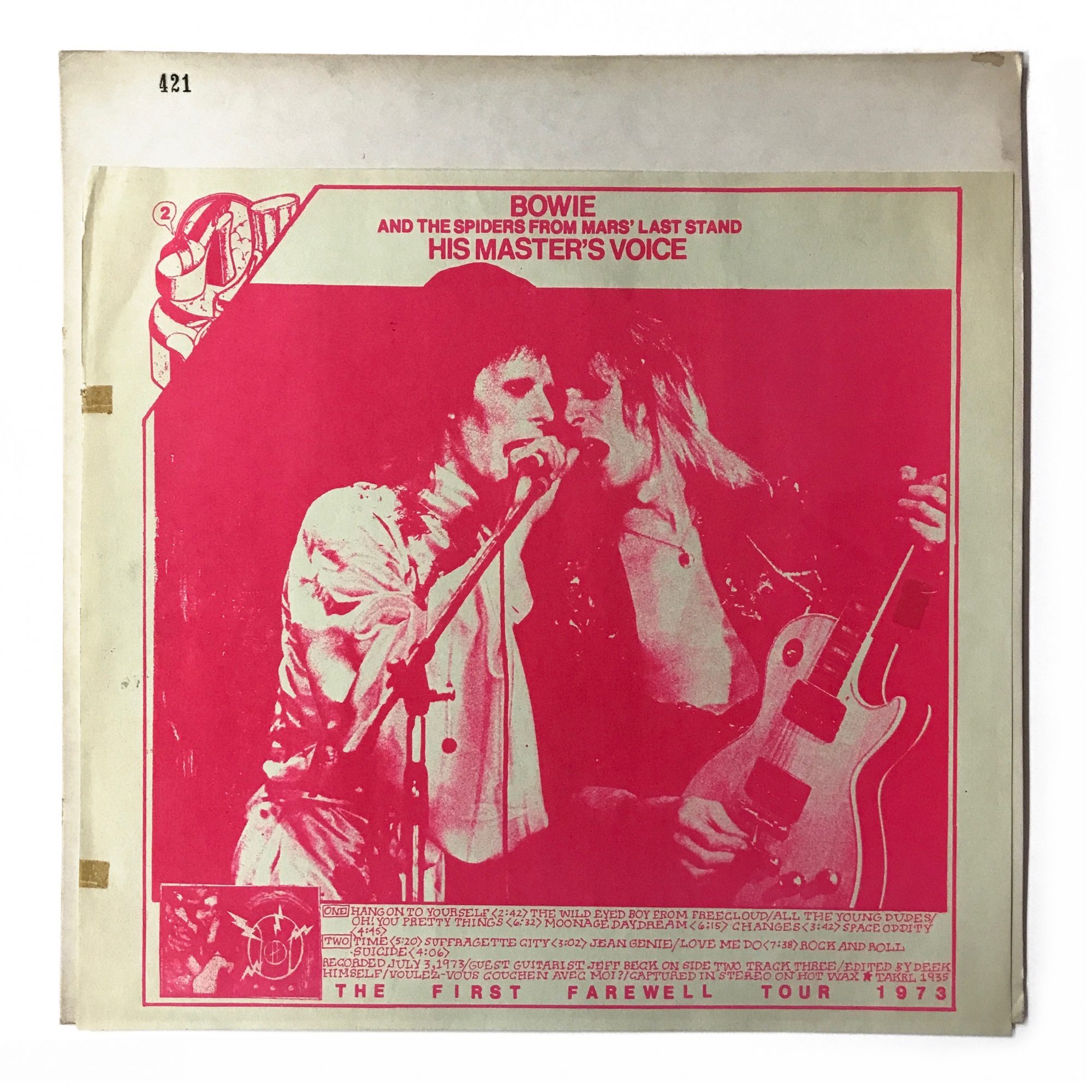

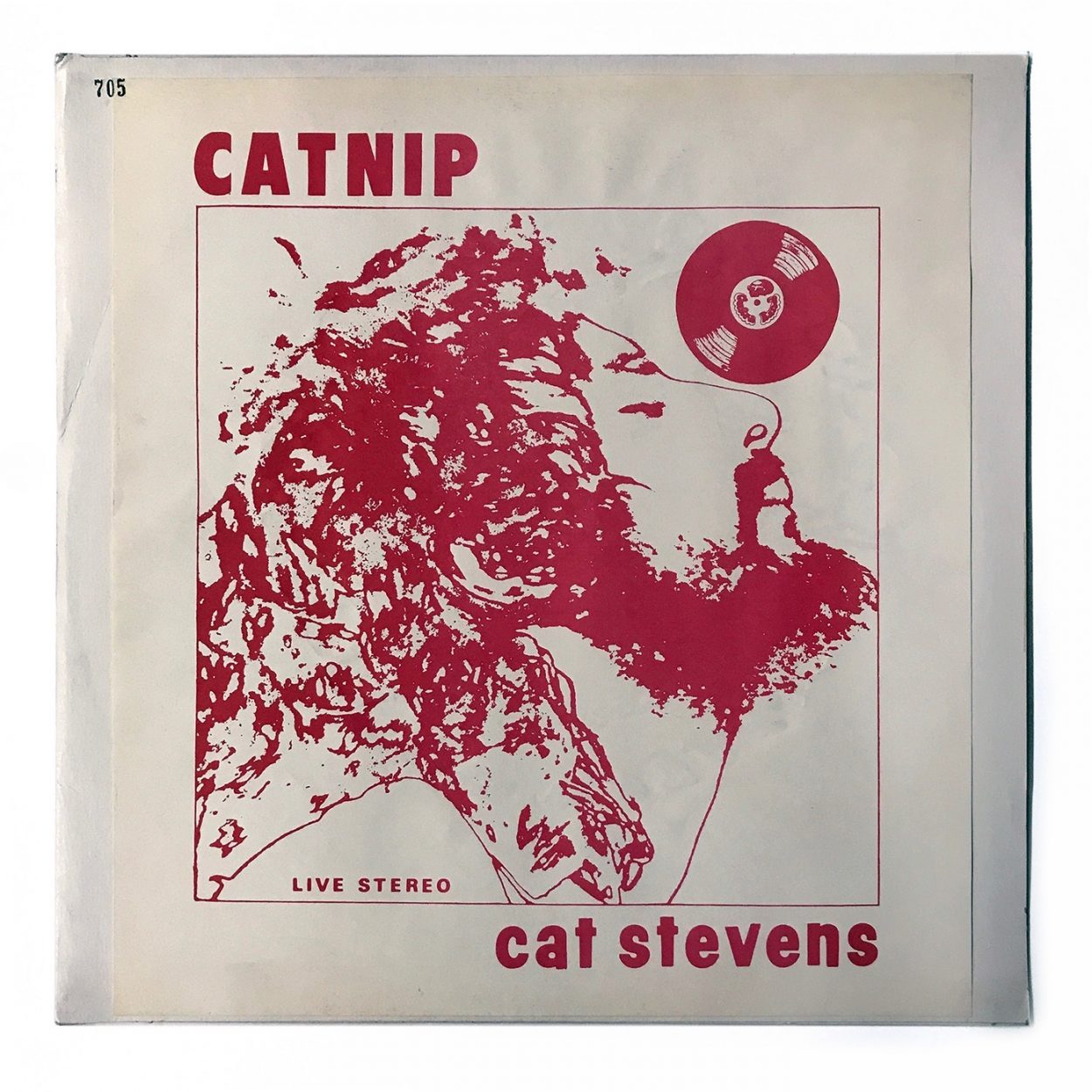

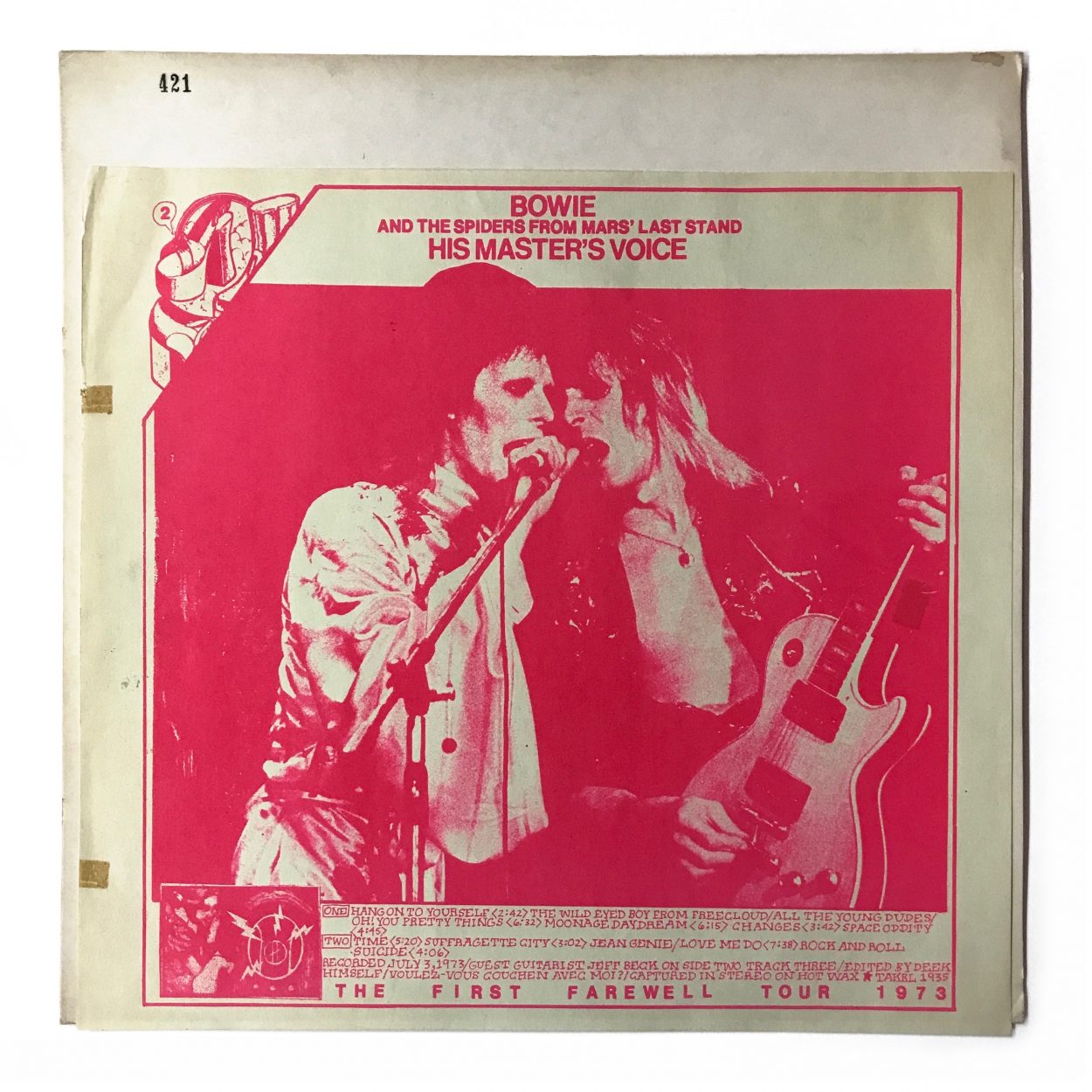

Simplicity worked too: ‘Catnip’, a live recording from the early 70s, came wrapped in a sweet drawing of Cat Stevens. It was issued several times, each edition printed with a different colour, a technique used on many bootlegs, including for the stylish paste-up cover of the ‘Bowie and The Spiders from Mars’ Last Stand’ of 1974.

The recordings on bootlegs came from a variety of sources – demo tapes and outtakes sneaked out by studio operatives and record company employees; radio and TV sessions; monitor mixes slyly captured by venues' sound engineers and of course concert recordings made by bootleggers and fans themselves. As awareness of covert activity increased, few could be as blatant as Dub blatantly holding aloft a shotgun microphone in the early days. Mike Millard (‘Mike The Mic’) was said to have made high quality recordings of over 300 concerts between 1973 and 1994 by pretending to be disabled and hiding his equipment in a wheelchair.

All of the big British artists of the day were bootlegged – often by outfits based abroad like TMQ: even when the intended market was the UK itself. Records would be pressed abroad because the legal consequences were less significant: in European countries like the Netherlands and Italy, there were virtually no sanctions at all.

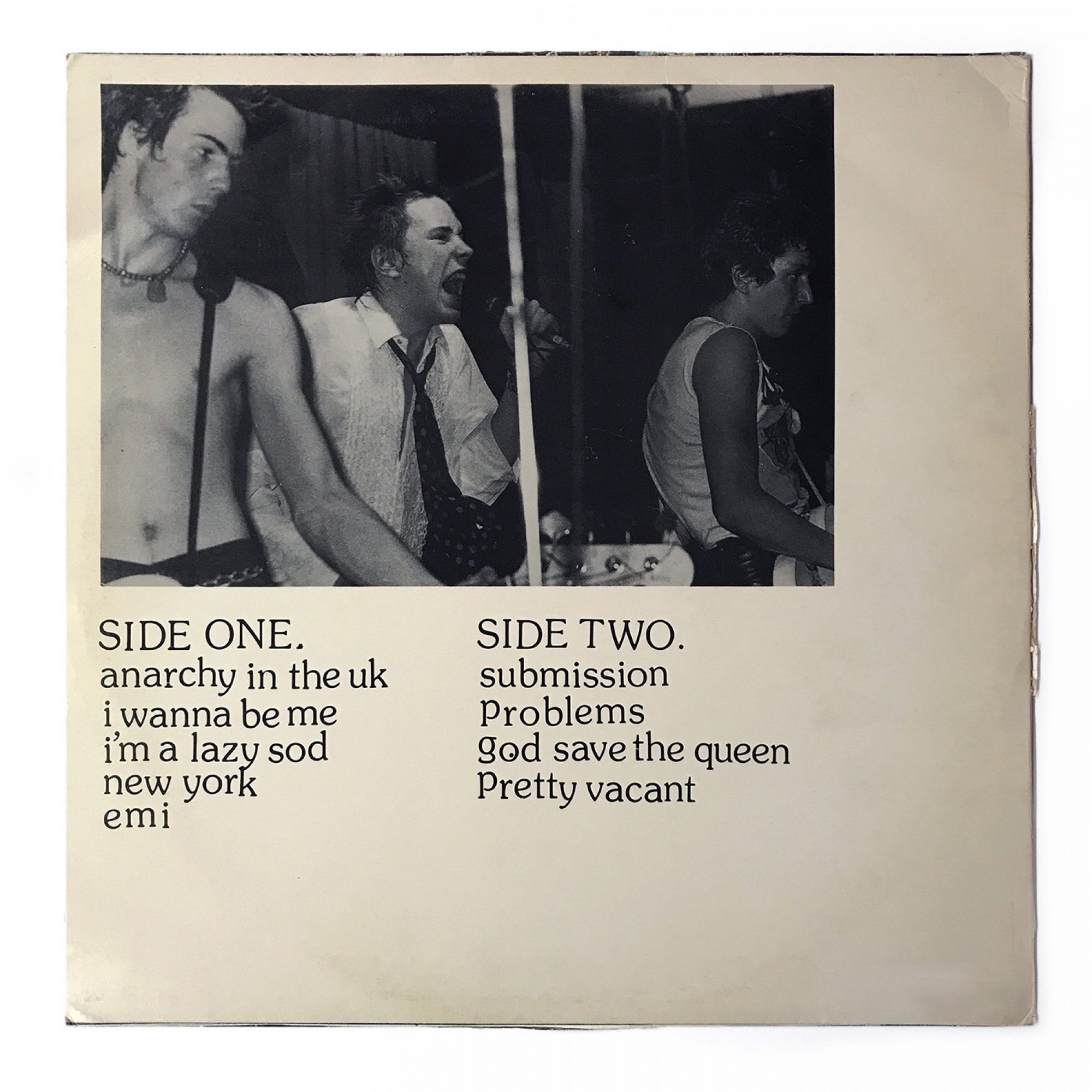

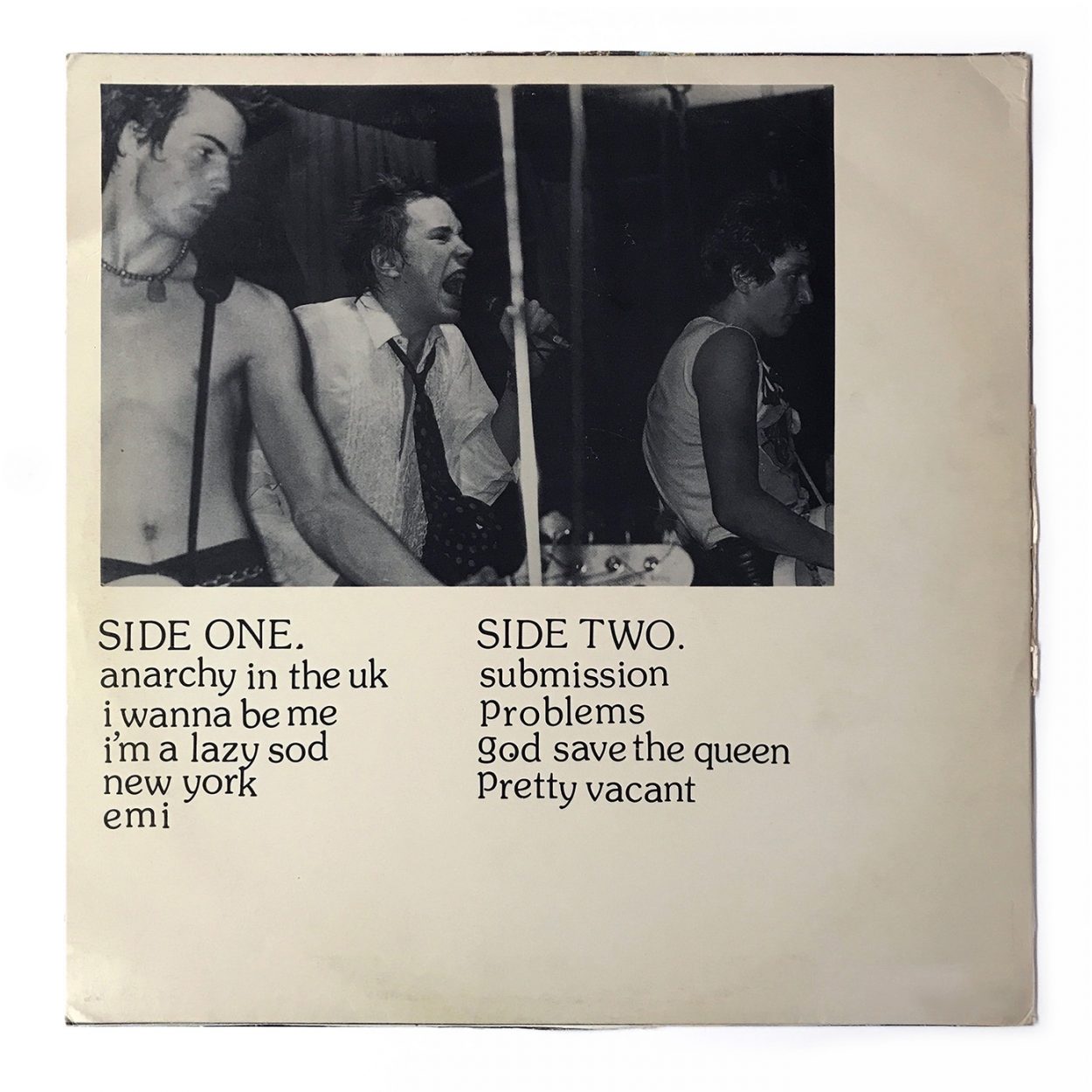

But, with the coming of punk, a homegrown bootleg culture really got going in the UK. The bands and the independent labels wielded far less legal clout than the rock monsters and the majors and there was something fundamentally in sympathy between the punk DIY attitude and the outlaw ethos of the bootleggers. Bootlegging in the Punk era also had a more important countercultural function, as it captured many of the influential bands' brief careers, or shifting line-ups: the ‘Anarchy in the UK’ single was the only official Pistols’ release with original songwriter Glen Matlock and the original legendary Buzzcocks line up with both Howard Devoto and Pete Shelley split after a couple of singles and a few gigs.

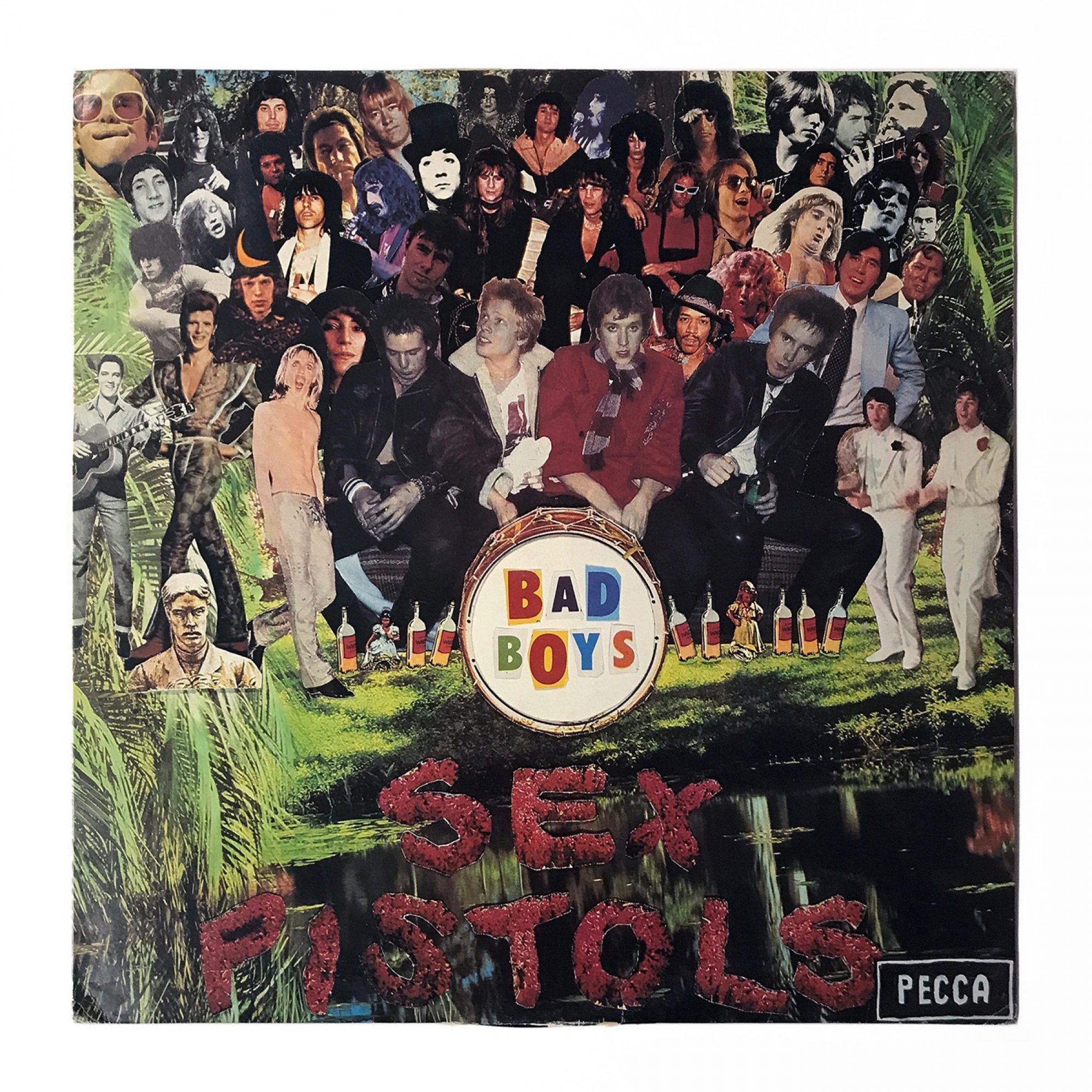

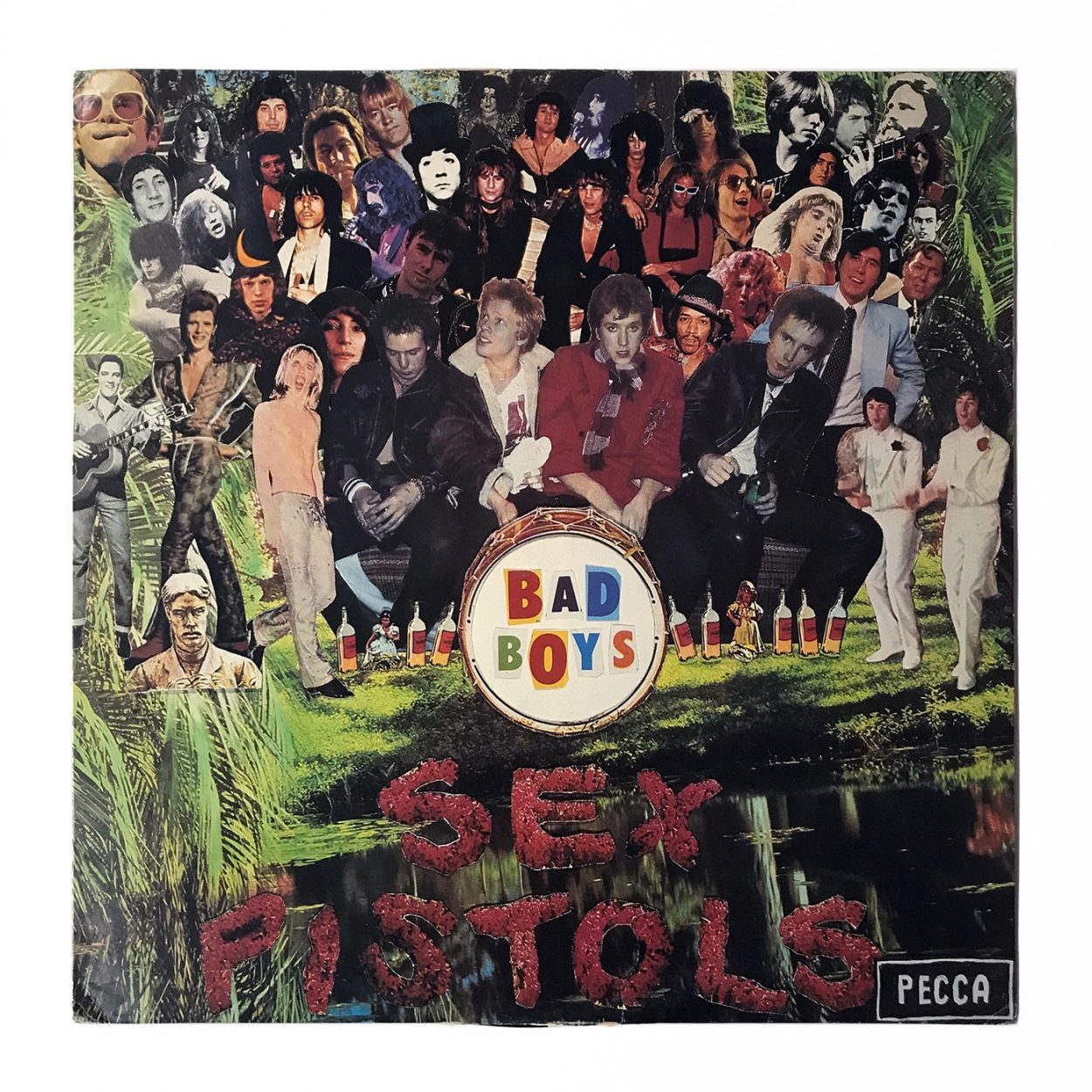

The Sex Pistols show at Manchester’s Free Trade Hall in June 1976, regularly hailed as ‘the most important gig of the 70s’, was only attended by around 70 cognoscenti (despite many more claiming to have been there) but was made widely available to fans by the historically valuable, if terrible sounding, ‘No Fun’ bootleg. ‘Bad Boys’, the Pistols bootleg of 1977 Stockholm concert (released by ‘Pecca’ records) has a take-off of The Beatles’ Sergeant Peppers sleeve with the original personalities swapped out for a bunch of rock’n’roll icons including Hendrix, Brian Jones, Lou Reed, Jim Morrison, Bill Hayley and the band themselves.

The BPI busts over the years were numerous if fairly ineffectual. Staff from the Anti Piracy unit accompanied by police officers would swoop on dodgy record stores or market stalls, confiscate all the bootlegs they found and make occasional arrests. But successful prosecutions were rare.

Confiscated contraband was all destroyed, but one copy of each bootleg was kept – presumably to provide a record of evidence in the court cases. When the BPI came to move premises from its Savile Row offices in 2005, some enlightened soul had the thought to offer the collection – over 4,000 albums, an unparalleled invaluable musical resource - to the British Library Sound Archive, where it now resides. Despite recognising bootlegs’ enormous cultural value, the British Library had previously not collected them because they did not want to be seen condoning illicit behaviour. Now ironically, major record labels come to the sound archive seeking bonus materials for new multi disc releases of their bands’ work, so the music lives on even if those who recorded it – for love, mischief, posterity or just filthy lucre – are gone.

Thanks to Andy Linehan and James Tugwell of the British Library Sound Archive for their assistance in the preparation of this piece and to Kevin Foakes for the photography.

Images courtesy British Library.

Stephen Coates is a music producer, author and broadcaster. His upcoming book Bone Music traces the history of the bootlegs of forbidden music cut onto X-ray film in Cold War era Soviet Union