The Personal Service of Mid-Century Broadcast Station Reception Cards

Thank you for your reception report. We gratefully acknowledge your communication. So read the postcards from international radio stations in Baghdad, Cairo, Jakarta, Kabul, New Delhi, Peking and beyond, sent to an amateur operator, Peter Gillman, in the 1950s and 1960s. Personal signatures of Chief Engineers and Radio Directors add to the effusive communication from major broadcasters, sent thousands of miles to a lone listener in Wallington, suburban Surrey.

QSL cards, as these missives are known, were an innovation of the 1910s when amateur radio was established internationally. For radio enthusiasts travelling the globe via their radio dial, QSL signalled the confirmation of a transmission using the Q-code system adapted from air traffic control. At its most simple, it means that a listener has heard a transmission and sent a card to say so. The transmitter sends a card in return to acknowledge receipt of the report.

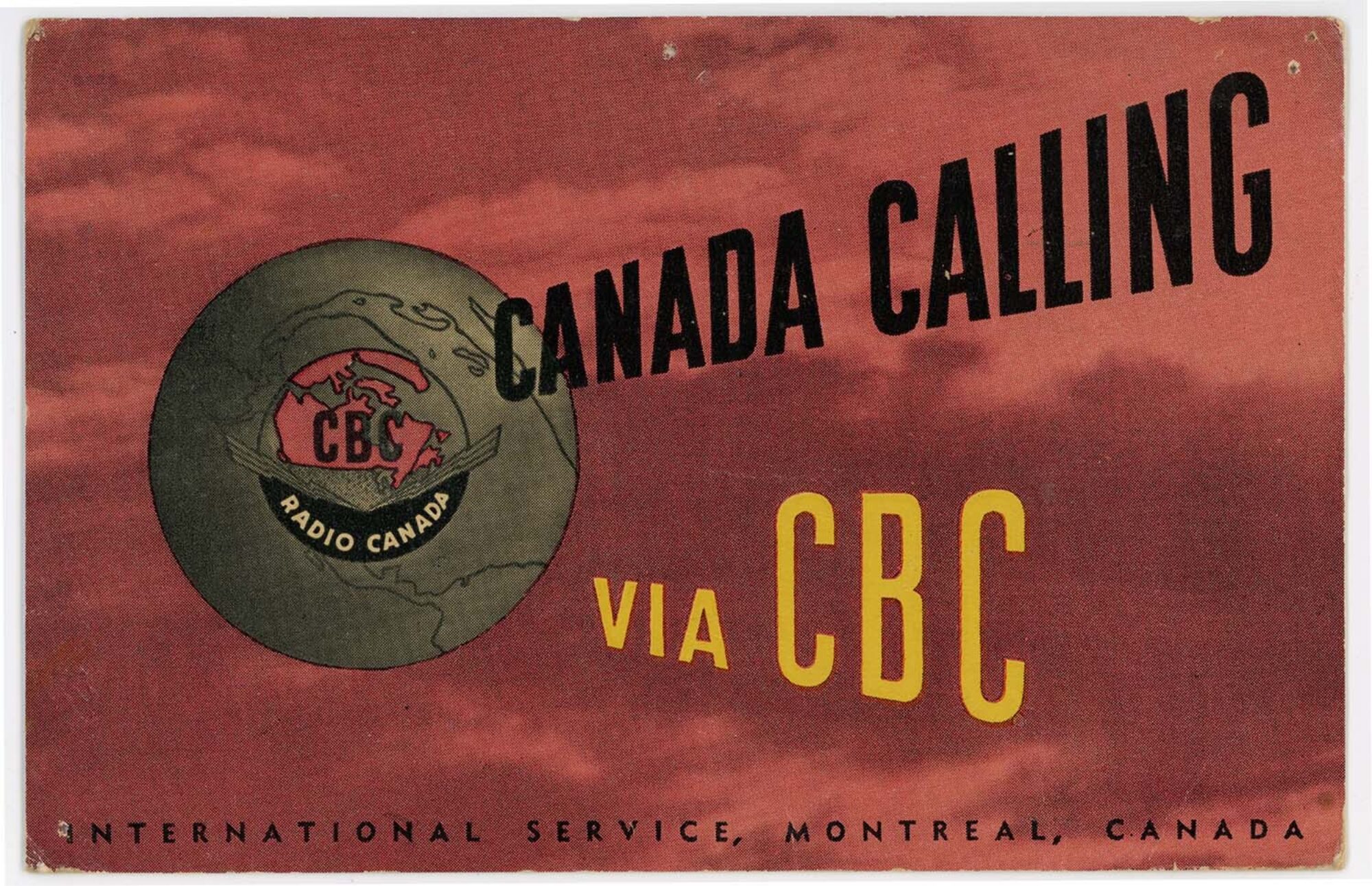

Short wave broadcasting spread rapidly into homes through the 1920s and 1930s. In the postwar years, in Britain, radio culture expanded with magazines designed to serve a growing set of radio producers and receivers. English-language programmes broadcast by international radio services could be picked up by enthusiasts in Britain with modest kit and an aerial strung along a picture rail or a garden wire parallel to a washing line. As broadcasters originally had no way of monitoring the reach of their signal, listeners’ reception records supplied valued evidence. In return for their reporting, listeners were rewarded with an attractive confirmation card.

QSL cards make aural radio communications material. They also form part of radio users’ etiquette, as a technical and pictorial thank you note. The tradition continues among amateur or ‘ham’ radio enthusiasts, who transmit person-to-person, and of whom there are some 2.5 million worldwide. International broadcasters, however, no longer individually correspond with their listeners to confirm that their programmes are heard.

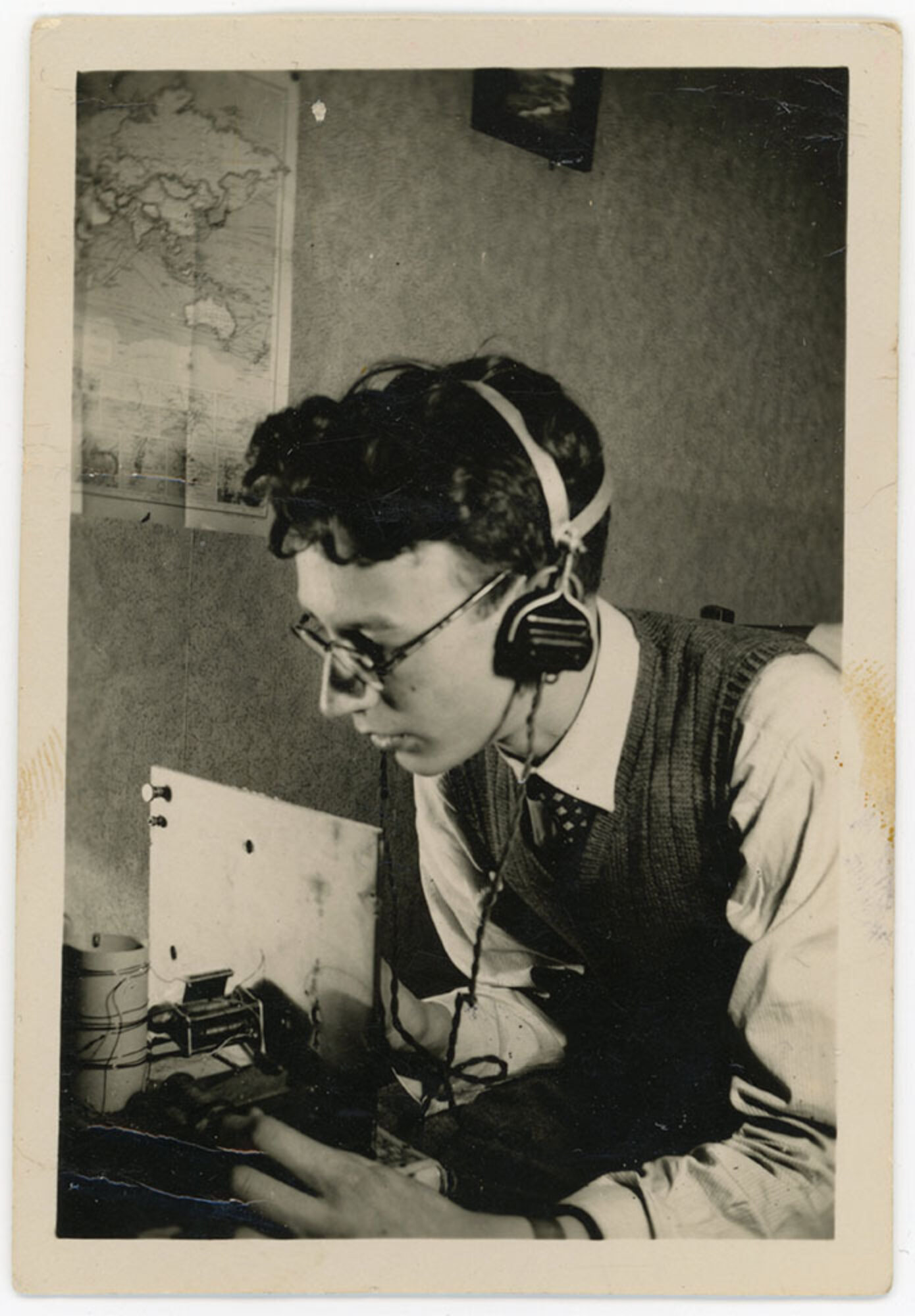

In his early radio ham years, Gillman set up operations in his childhood bedroom. By age 16, in 1950, he qualified for a radio licence and a personalised call number (G3729). In the same year, he ranked in the top 40 of competitive QSL card ‘chasers’, with 16 countries to his name. The following year, his photograph appeared in Short Wave News, dressed in shirt and tie, spectacles and headphones.

The photograph of Peter Gillman which was reproduced in Short Wave News

Gillman was my partner’s father, and we keep his QSL card collection in our house. They tell a story of global communications mostly conducted privately in sheds. Radio operation is a solo practice, but it is not isolated. As well as friends who shared Gillman’s interest, magazines and clubs created networks. Radio hams are a global community, mostly male, often with a passion for technology. Amateur operations might overlap with professional interests or offer respite from them. Gillman’s practices were connected to his job in the mid-1950s as an air traffic controller at London Airport (now Heathrow) and it continued interests he developed in the RAF on National Service aged 18-20. Gillman was bitten by the bug in boyhood; his best friend’s father was a radio ham.

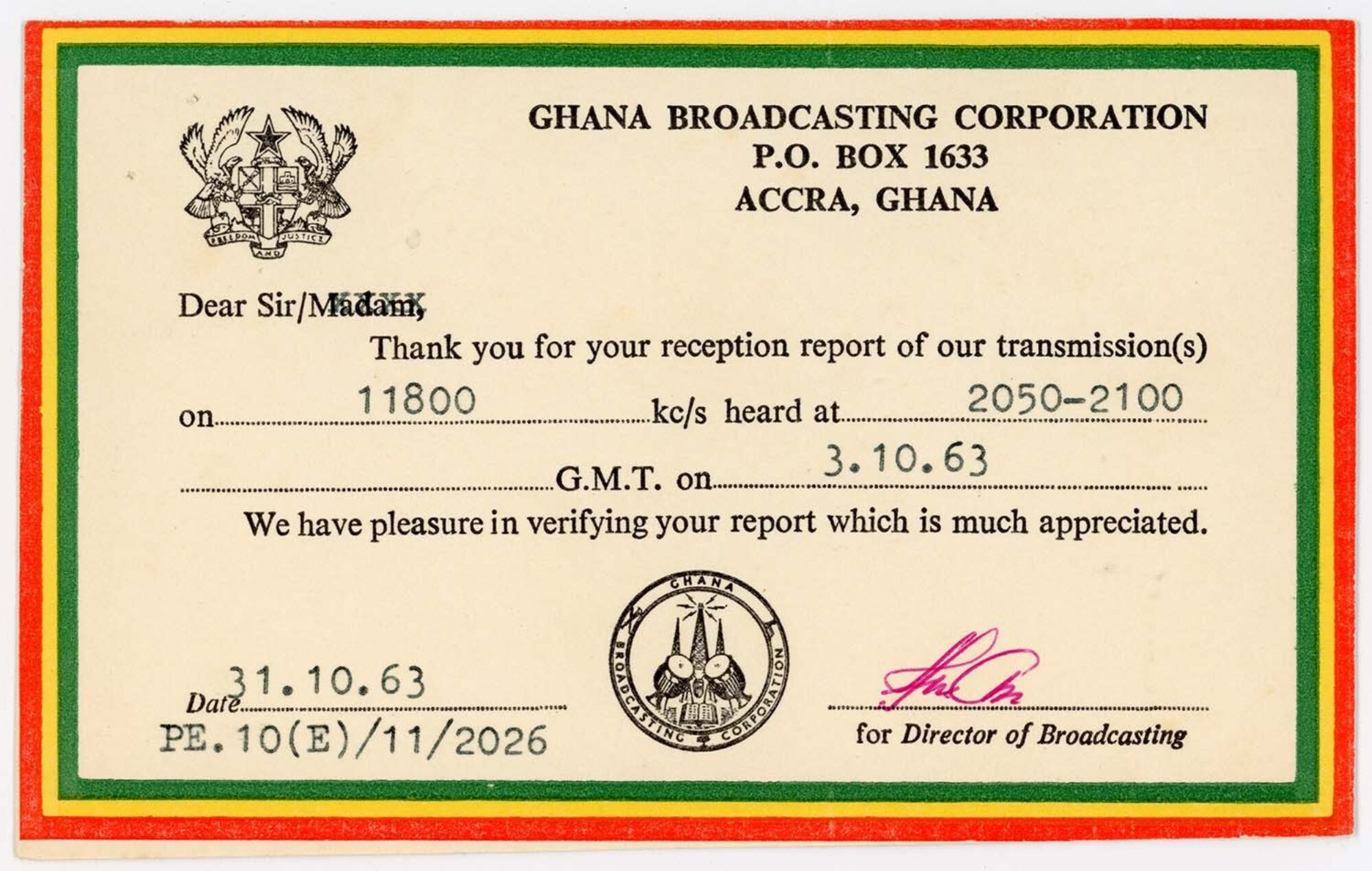

Distance (known as ‘DX’) radio listening shares elements with one-to-one radio communications - including the sending and receiving of QSL transmission receipt cards – and some amateurs, including Gillman, undertook both. The priority of DXers, however, is to seek out and listen to international broadcasting stations rather than to transmit themselves. DX QSL cards are verifications (they are also known as ‘veries’). Listeners testify that broadcasts are audible, and broadcasters acknowledge listener engagement. Several international radio stations in the 1950s and 1960s considered their service to be an international correspondence club; they used QSL cards to generate audience feedback about programme content.

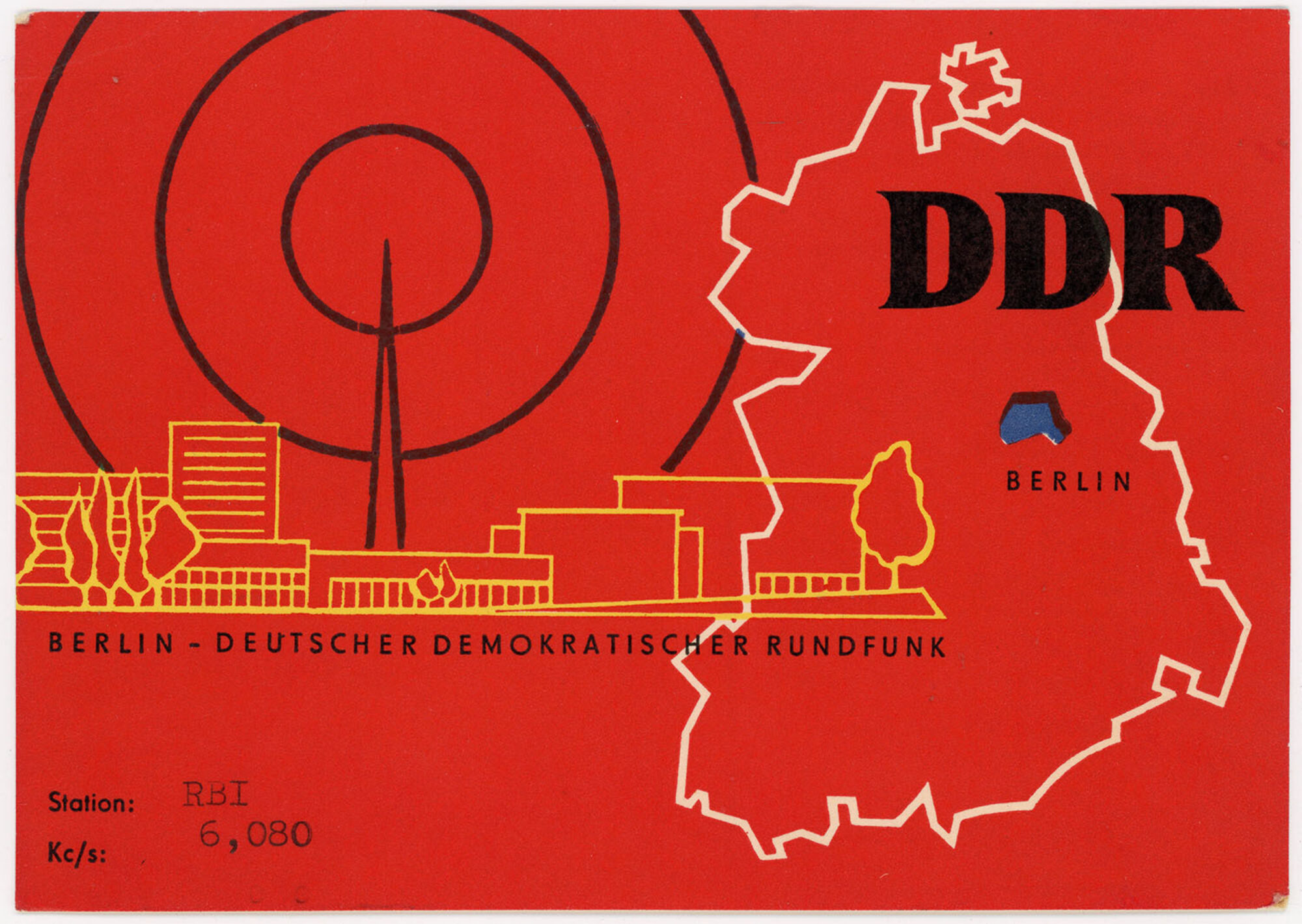

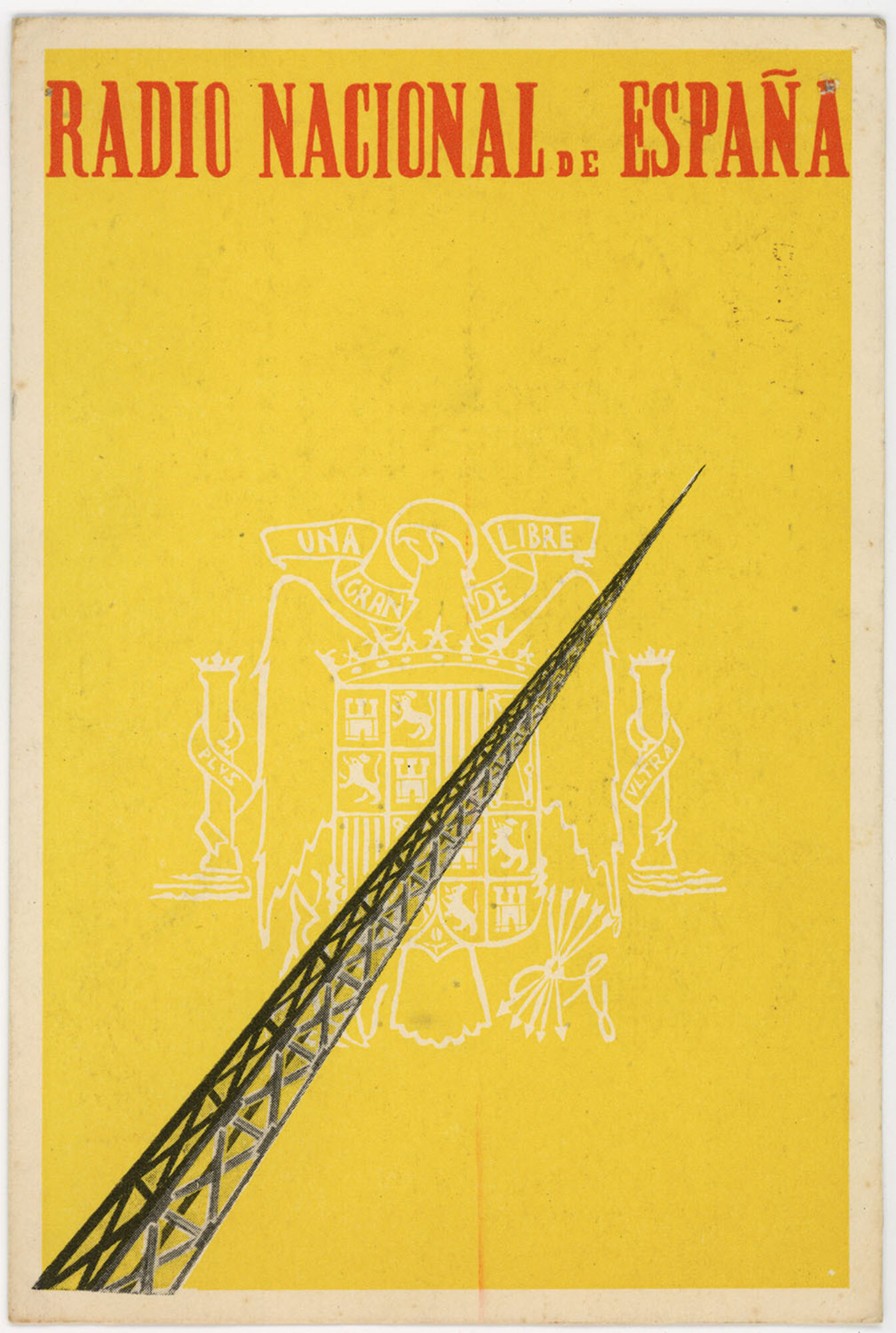

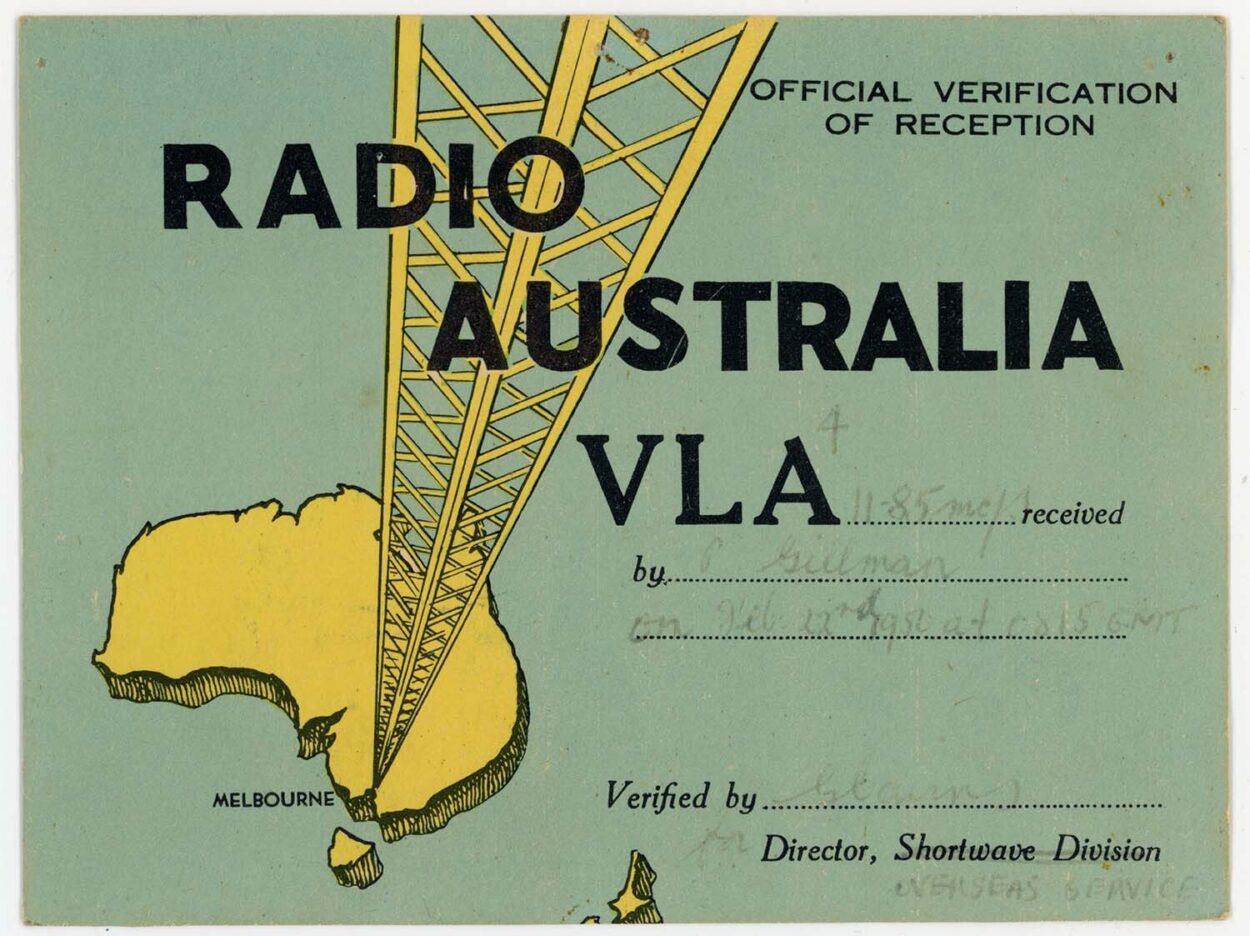

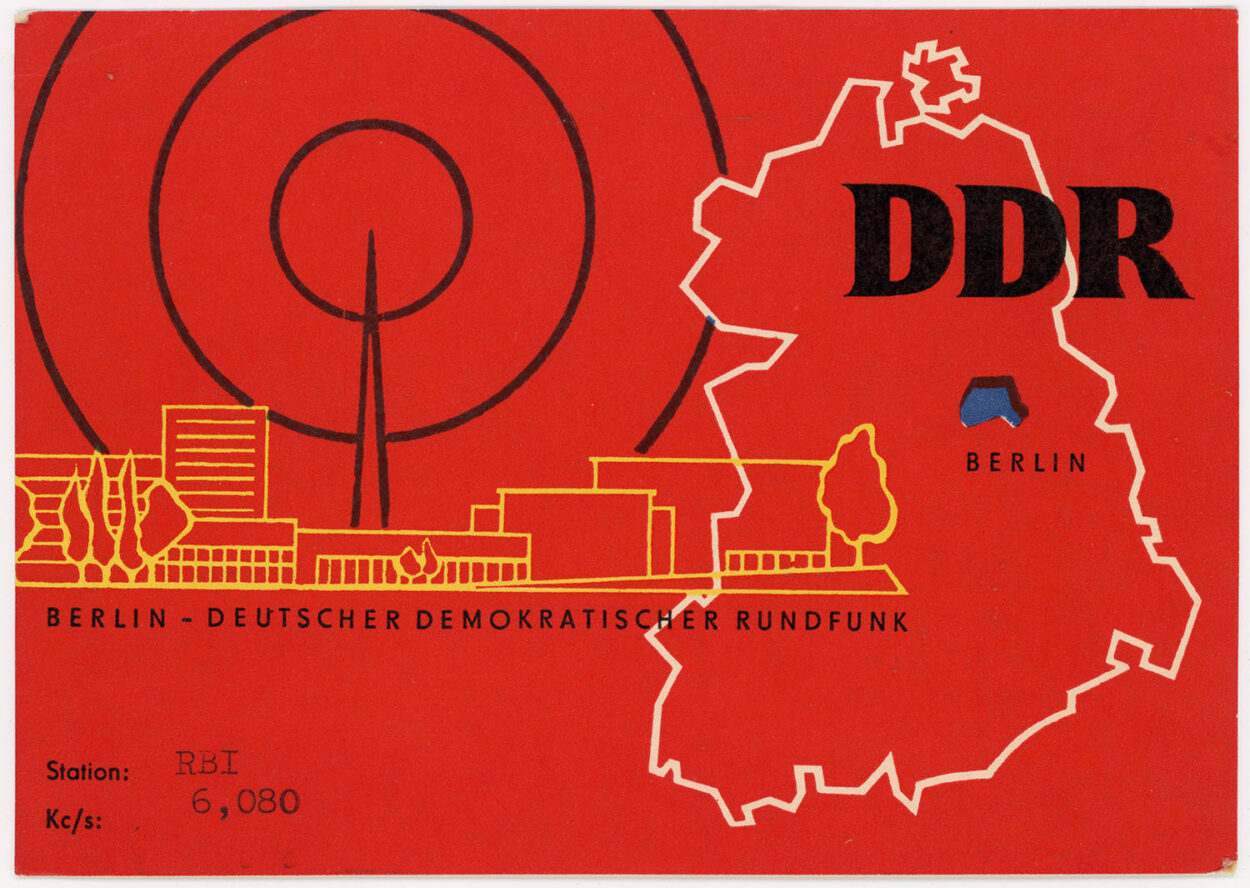

Amateur QSL cards might contain hand-drawn illustrations or personal photographs. The more professionally produced cards come from larger broadcast stations. Across the six continents represented in Gillman’s collection, design motifs include maps and flags, and local or national indicators from snowy mountains in Austria to elephants in Morocco. Radio signals are visualised by stylised masts, vibrating lines and concentric rings. Cards were personally addressed to a ‘Dear Listener’ or ‘Dear Radio Friend’, with handwritten data about radio frequency and equipment, dates and times. They were simultaneously advertisements for services (programme schedules were available on request), quality control devices (monitoring signal reach) and community building exercises (creating bonds between broadcasters and their publics).

For the armchair traveller, whose visits to the broadcasting country largely happened remotely, postcards provided souvenirs of an aural journey. They might include tourist information from population figures to topographical details. Some depicted national flora and fauna. Radio Sweden, who boasted ‘the largest number of radio receiving sets per inhabitant in Europe’ in 1950, included musical notation of the first notes of a song by eighteenth-century composer Carl Michael Bellman. They were brochures promoting places their listeners may never visit (and Gillman travelled to very few destinations). The furthest broadcasts – from Radio Australia, represented by a mast stretching vertically from Melbourne into space – stretched over 10,000 miles. At a time when international travel was a rare luxury and long-distance telephone communications expensive, they carried decorative stamps and penfriend-like inscriptions. Pin holes show that Gillman put cards on display.

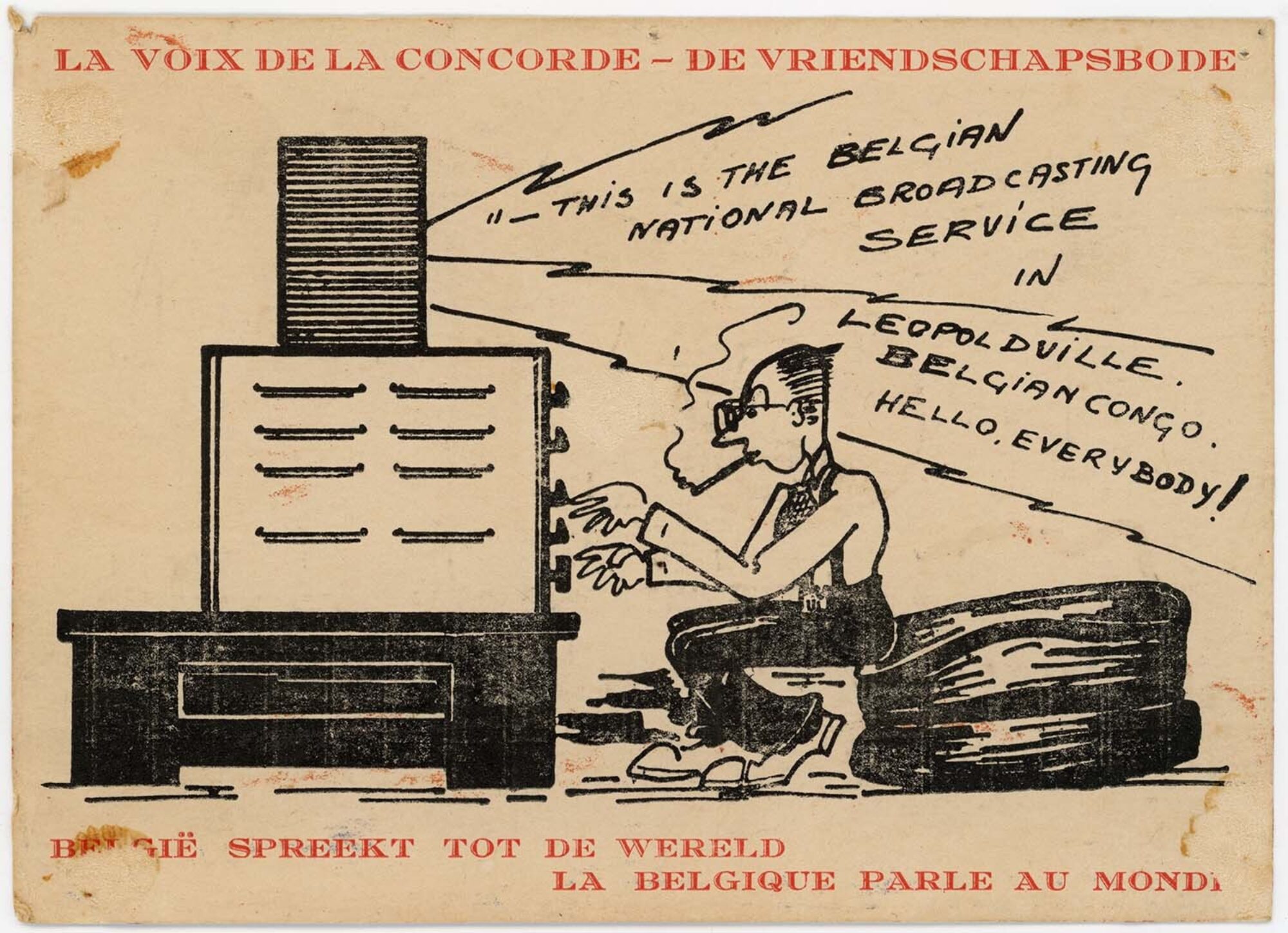

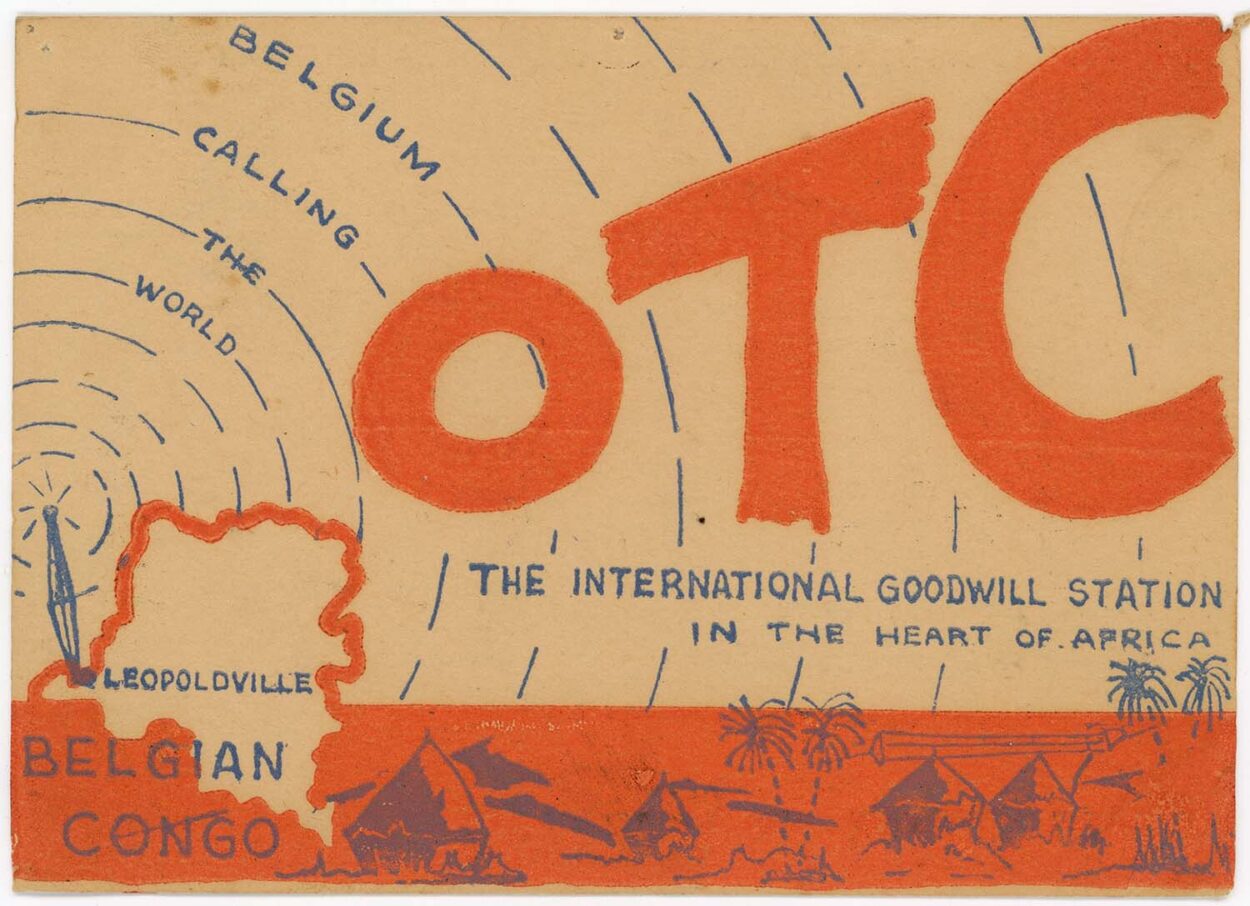

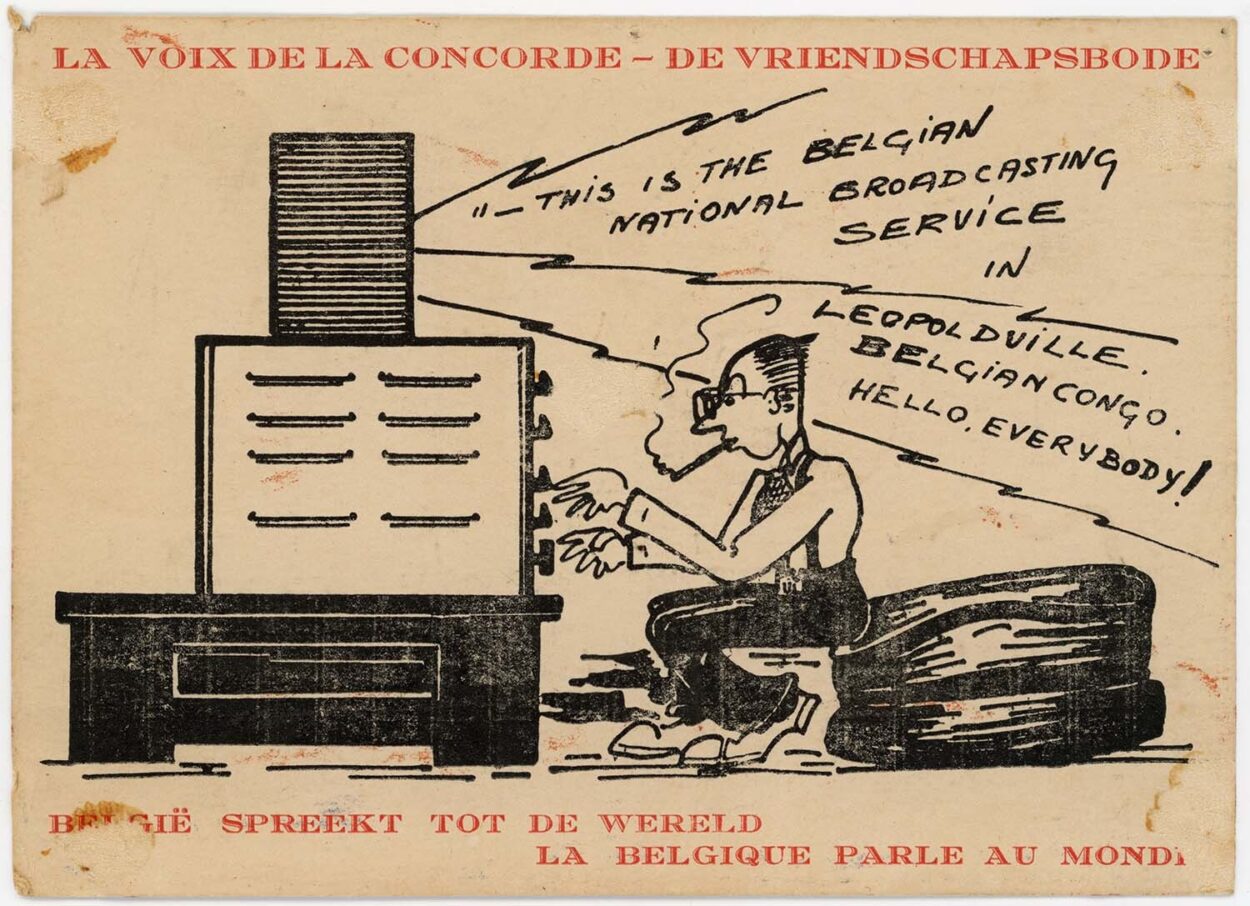

Positioning QSL cards in colonial context, the propaganda purposes of international radio services are transparent. OTC, for example, styling itself as an ‘International Goodwill Station in the Heart of Africa’ in what was Leopoldville, Belgian Congo until the early 1960s, and now, since independence, Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of the Congo, shows an illustrated bespectacled white man in shirt, tie and braces twiddling knobs on substantial radio apparatus. The opposite side depicts simple mud-and-thatch huts dotted between palms. In the context of the forced labour, apartheid systems and brutal imperial violence wrought against indigenous populations under Belgian rule, the communications assume the ‘friendship’ and ‘concord’, promised in French, German and English, to be an exclusively European privilege.

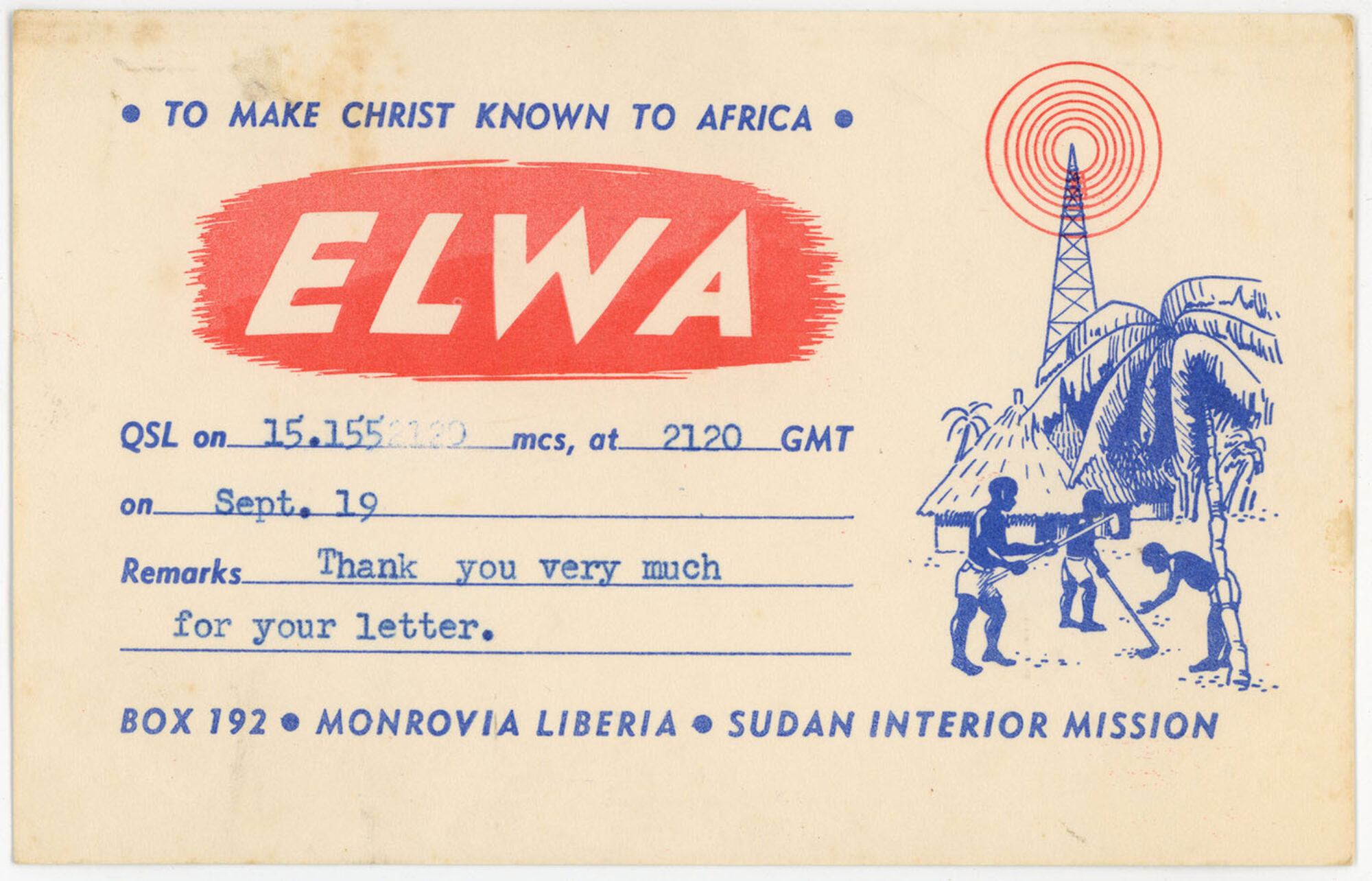

A similar set of visual motifs – radio mast, mud hut, palm tree, but with additional black labourers tilling the soil – was used to illustrate the Christian radio station ELWA. An acronym of Eternal Love Winning Africa, ELWA was a major missionary broadcaster established in 1954 in Monrovia, Liberia, by two white American evangelists. Their purpose was to convert the continent to Christianity with the help of 240-foot broadcasting towers, the distribution of portable wirelesses, and a programming schedule in forty-two languages. Their station offered news, bible study and American gospel music. Gillman was an atheist on the other side of the globe who collected the messages without comment.

ELWA QSL card

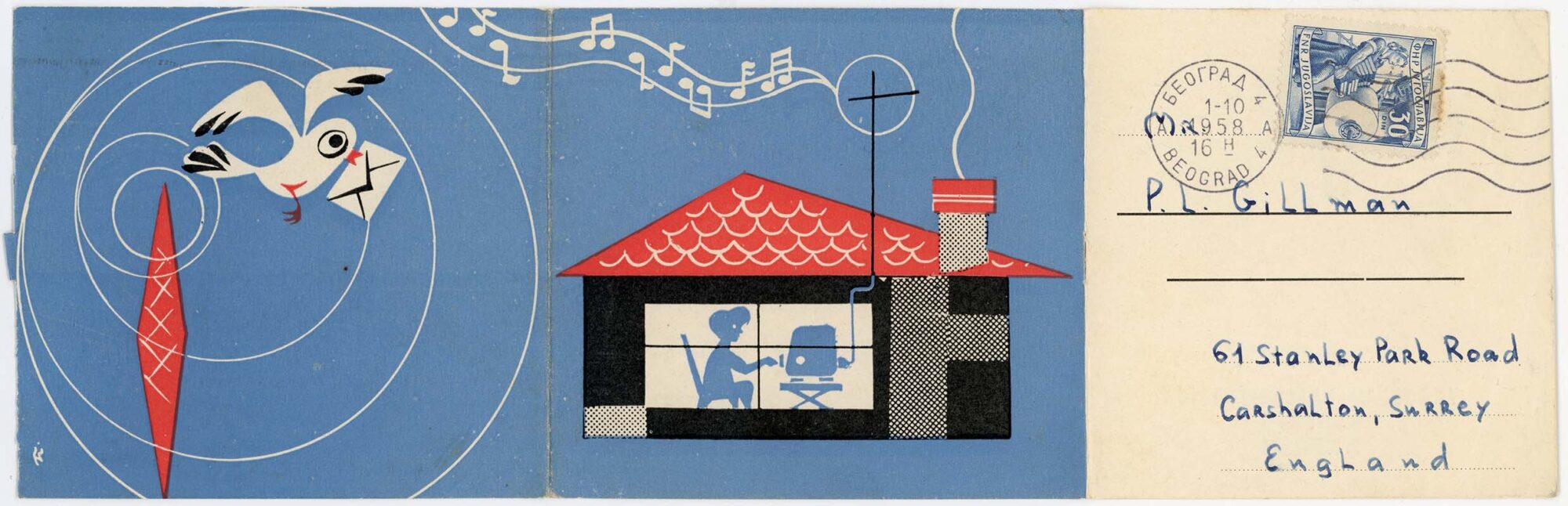

QSL postcards are mementos of a turbulent Europe whose borders were regularly redrawn in the years Gillman tuned in. Some illustrations show domestic listeners in blissful ignorance. Radio Beograd’s folding card features an illustration of a white dove with an envelope in its beak as a symbol of the emissary function of radio. The bird travels from a broadcasting mast to the receiving aerial of a red roofed bungalow. Through the window we spy a quiff-haired man, picking up music through his device. In accompanying text, the transmitter offers a ten-language ‘foreign service’ devoid of explicit reference to politics in former Yugoslavia.

Yugoslavian QSL card

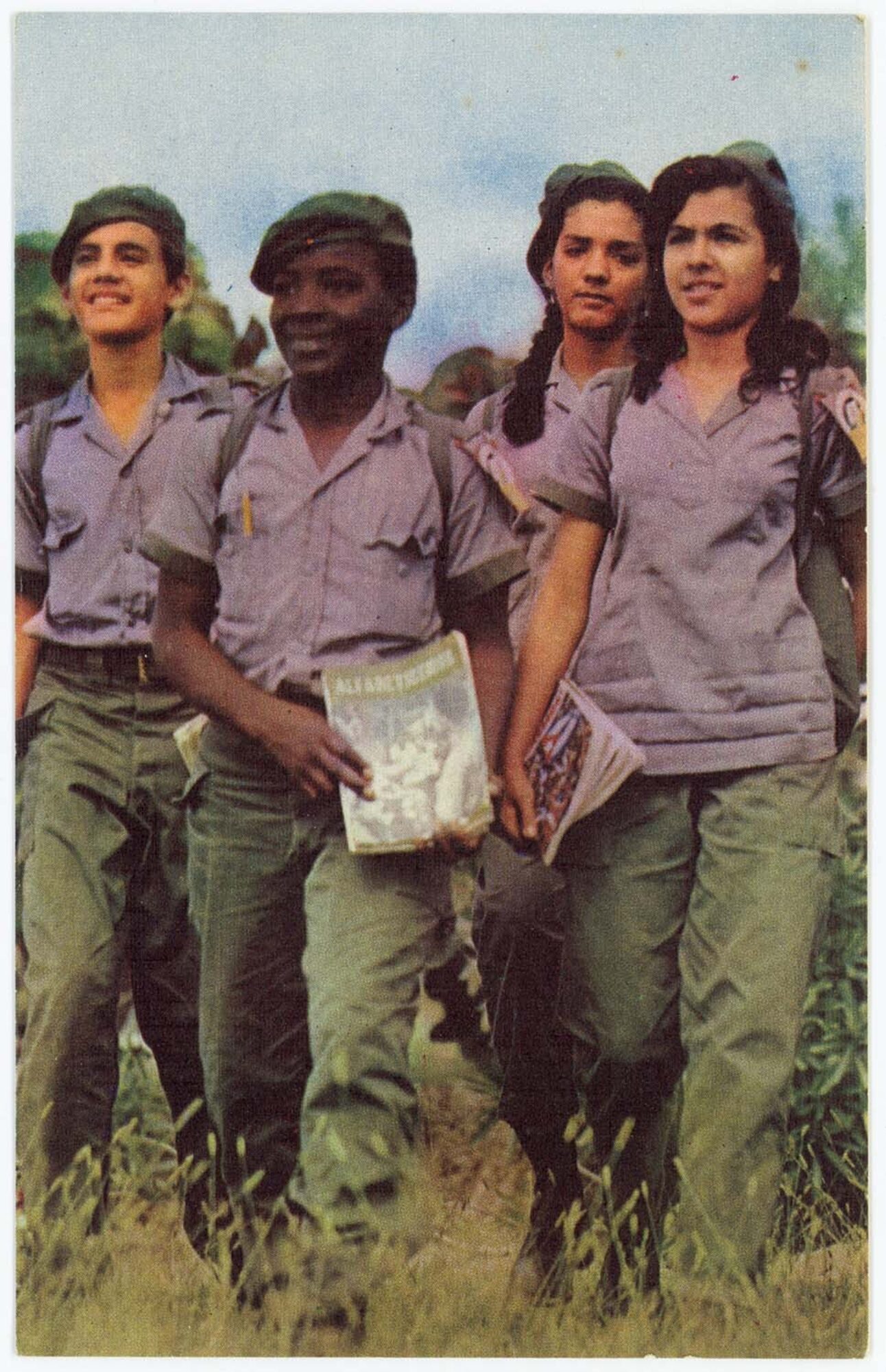

Elsewhere, politics are centred. Postcards from German Democratic Republic (East Germany) promote shipbuilding prowess while thanking Gillman for his reception report in 1958; later they style DDR Broadcasting House as ‘the voice of peace’. In 1963, Radio Cuba in Havana sends a colour photographic postcard of multiracial young revolutionaries striding out in khaki fatigues and berets. In the Cold War, a soft power battle for hearts and minds took place through music and light entertainment. Radio Free Europe was introduced in the 1951 issue of Short Wave News that featured Gillman’s photograph. It claimed to ‘get the American way of life into Iron Curtain Countries’. Radio Moscow, meanwhile, promoted opportunities to ‘Meet the Soviet citizen in his everyday life. Learn what’s doing in the land of Socialism’.

Cuban QSL card

Short Wave News detailed English language programmes that a DXer might enjoy in the early 1950s: world news; music including Samba and opera; cricket matches in Barbados; national anthems including God Save the King in Southern Rhodesia. There are notes too on interference. Listeners wanting to hear English programming from Accra were warned that the frequency was also used by a station providing weather reports in German. Baghdad’s waveband was so interrupted by QRM (human made noise) ‘that little is intelligible’. Fortaleza in Brazil had an excellent signal ‘ruined’ by Russian ‘jamming’. From 1948, soviet governments inserted intentionally irritating sounds to block Western broadcasts, including the BBC. Sounds ranged from bird chirps to mechanically produced white noise. The spillover caused disturbances on adjacent frequencies.

QSL cards are international records, but they are also personal achievements. They demonstrate stations that have been correctly identified from carefully scanning the bands. They are testament to hours inputted by listening around the clock (time differences were not always sociable). They are tangible outcomes of aerial pursuits. Gillman’s cards were accrued regularly until the late 1960s when they become more sporadic. In the 1970s, he became a Citizen Band (CB) radio enthusiast: a natural progression for a short wave ham. Gillman’s collection is relatively modest - by the 1980s, serious DXers in the US boasted collections of over 1000 cards - but they are a material outcome of an enduring hobby.

At Gillman’s death in 2021, he left around 60 cards in a flip-style album, along with dozens of radios, large and small, historic and recent. He remained a loyal friend of the airwaves, even after broadcast stations stopped sending personally addressed cards to thank their listeners for tuning in.

Annebella Pollen is Professor of Visual and Material Culture at University of Brighton, UK, where she researches undervalued archives and untold stories in art and design history. Her books include More Than A Snapshot: A Visual History of Photo Wallets, Mass Photography: Collective Histories of Everyday Life, The Kindred of the Kibbo Kift: Intellectual Barbarians and Nudism in a Cold Climate: The Visual Culture of Naturists in Mid-20th-Century Britain.