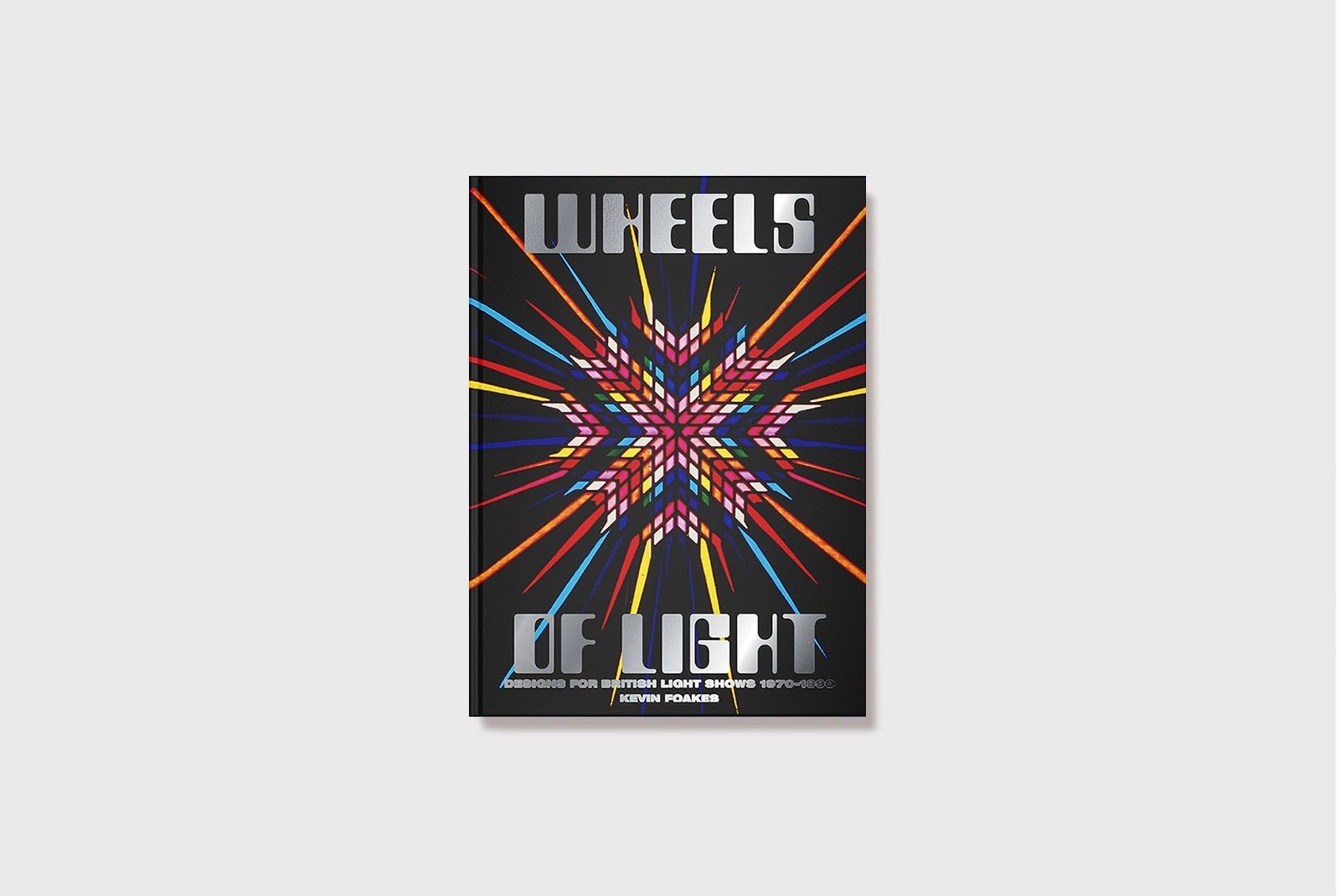

Andrew Wilson traces the origins of British light shows from when a small group of artists in London began creating experimental performances which paved the way for this wholly original new art form, in the years before the commercial artwork featured in Wheels of Light.

As early as October 1967 — the summer of love having just ended — the light show was recognised in Encounter magazine as ‘the only original art form associated with the underground’. Like much contemporary art of the mid-1960s it challenged the status of the art object through its form, content and media. It was both performative and ephemeral — event rather than object — and when deployed in its usual form as an integral part of a stage act it was also a trans-disciplinary and collaborative art form. It additionally challenged conventional ideas of authorship — in effect many light artists were using a found process that they framed and initiated, but where control was questionable and the outcomes could often be hard to predict through their activation of random variables; the shifting material images that resulted being in many respects akin to Brownian Motion that created a biokinetic art.

The early mixed projections of slides, light and film used as part of the season of jazz/poetry events put on at London’s Marquee club by Live New Departures in 1963, or three years later at the same venue through the summer of 1966 as part of the weekly Spontaneous Underground events organised by Steve Stollman, had developed from a mood-enhancing use of what were effectively an extension of theatrical lighting techniques. Both sequences of events at the Marquee provide a partial prehistory for the emphatic emergence of the light show in the autumn of 1966 and its fairly immediate flowering by the end of the year. At these events the free improvisation group AMM with Cornelius Cardew or Pink Floyd, along with poets and other performers might have coloured lights or films projected over them as a way of breaking down perceptual barriers between audience and stage. The arrival of Toni and Joel Brown from Timothy Leary’s Millbrook community in upstate New York is often taken as a catalytic event for the development of the light show in London, projecting slides over Pink Floyd at one of the Sound and Light Workshops at All Saints Church community hall, which had been successfully organised as fundraisers for the London Free School through the autumn of 1966. The truth of the matter was that the marriage of light show to psychedelic music became an inevitability as venues opened and the demand for such an integrated immersion in long stretches of improvised music grew exponentially. By the end of the year, Pink Floyd had replaced the Browns’ rudimentary projection of images with their own built lighting rig with integrated projectors operated by Joey Gannon who was friendly with Mike Leonard’s Hornsey College of Art Light/Sound workshop, and later joined by Peter Wynne-Wilson who was well versed in theatrical lighting.

Encounter not only identified Mark Boyle as the pioneer of this new but burgeoning art form, but also explained that ‘there are now at least twenty-three separate light-show specialists from whom equipment and operators may be hired’ — all of whom had been earlier listed in an unsigned article on the light show phenomenon in a June 1967 issue of International Times. Boyle, working with his partner Joan Hills had been creating projections as part of their performance happenings since May/June 1963 and their first projections for Live New Departures at the Marquee. Coming out of a collage sensibility, their interest in the detritus of life proposed a new form of realism. Not images or metaphors of something else, no play of illusion, Boyle and Hills embraced the stuff of life as their material and subject — leading them to aim at including everything in their work; as Boyle explained, ‘the only medium in which it will be possible to say everything will be reality I mean that each thing, each view, each smell, each experience is material I want to work with… There are patterns that form continuously and dissolve.’ Their events were correspondingly diverse but invariably included projections of light, films and slides until in 1966 they created works focusing on elemental forces of cycles of life conceived as sound and light projections — Son et Lumière for Insects, Reptiles and Water Creatures focused on living organisms which were taken out of their habitats, isolated and projected; Son et Lumière for Bodily Fluids and Functions included projections of fluids taken from both Hills and Boyle’s bodies (catarrh, blood, ear-wax, sweat, tears, urine, vomit, sperm) and Son et Lumière for Earth, Air, Fire and Water addressed physical chemical changes (such as evaporation, corrosion, crystallisation or combustion) in different materials and substance again projected onto large screens. The concerns of these events coincided with the evolving theories of auto-destructive and auto-creative art that the artist Gustav Metzger had elaborated since 1959 and were to a degree brought to public attention in September 1966 through the events surrounding the Destruction In Art Symposium that he co-organised and which had included Boyle and Hills. Metzger had similarly included projection in his performative lecture-demonstrations and since the early 1960s had been perfecting a form of liquid crystal projection with the aim of creating immersive environments of continuous states of flux that expressed directly the cathartic dialectic of auto-destructive / auto-creative art — projections that were realised and presented in 1965 and 1966, and then at the end of 1966 as a light show for concerts by Cream, the Who and the Move at the Roundhouse where an environment using twelve projectors was created.

As a direct development from the events at All Saints Church Hall, the Friday-night UFO club was created at a venue on Tottenham Court Road, and Boyle and Hills were booked to make a separate presentation for the opening night of the club on 23 December 1966. They presented Son et Lumière for Earth, Air, Fire and Water, but were then asked to continue projecting all night. And following the success of this they produced light projections every Friday night at UFO, not long afterwards providing light projections exclusively for Soft Machine in addition to their weekly spot for UFO. Through 1967 they presented projections — whether for Soft Machine or within an art context — at a frenetic pace that culminated between January and April 1968 joining Soft Machine’s tour of the USA with Jimi Hendrix. In many respects, the light show has been primarily understood as an integral part of American hippie psychedelia. Yet, just as Boyle & Hills’ assemblages and events were distinct from the American Happenings movement of Allan Kaprow, Al Hansen, George Brecht and Dick Higgins, so too were their light projections very different from those found in America. The Americans, notably Glen McKay at the Winterland Ballroom in San Francisco, ordered the light effects to the pulse of the music. For the dates at the Winterland, near the beginning of Soft Machine’s tour, the screen was split so that on one side McKay projected in the West Coast manner and on the other side Boyle & Hills made their light projection and rather than project to the beat of the band, as Boyle recalled ‘we just set the chemical reaction going. But somehow it always seemed to synchronise because there was always something happening on the screen. Or your mind made it synchronise. So I suppose in Europe we always thought that it was more exciting than when you were forcing it — your head was forcing the synchronisation and making it happen.’ With his synaesthetic light shows, Boyle consistently threw the performance back to the audience letting them find their own location between the tactile psychedelic sound of Soft Machine and the accompanying light show. The light show and its relationship to the music reveal the same ‘patterns that form continuously and dissolve’ that ‘are not just patterns of line shape colour texture, but patterns of experience’.

Andrew Wilson was Senior Curator of Modern & Contemporary British Art, and Archives at Tate 2006-2021, deputy editor of Art Monthly 1997-2006, and a freelance art critic and art historian since 1988. He is a founding fellow of the London Institute of ’Pataphysics.