Over the past 40 years, Ed Hall has made over 800 banners for a wide range of protests and campaigns that have made headlines: his archive is a visual compendium of the history of leftist struggle since the 1980s.

After school in Norwich, Ed studied architecture at Sheffield University and it was there for the first time that he saw the reality of Britain’s industrial heritage: the factories and the thousands upon thousands of working people who kept the wheels turning. It was a revelation and he realised that the country’s industrial might had nothing at all to do with the aristocracy or the royal family. It gave him what he calls:

‘A hostility towards people who take the cream off the top, give themselves titles and then claim to be the reason for Britain being wealthy.’

After graduating, he spent six years working for Liverpool Corporation building council houses before moving to London; first to Greenwich and then to Lambeth where he arrived in 1973. It was here that he would spend the rest of his professional life, working as an architect in the council’s Borough Development department.

At that time, local London councils and the Greater London Council had a degree of autonomy that allowed them to raise money and spend it on the provision of local services and housing. Lambeth was a Labour-led council and by the 1980s they were building 1,000 new council houses a year, however their spending priorities were at odds with Margaret Thatcher’s Conservative government who increasingly sought to restrict council spending powers: an ideological struggle that Ed was at the heart of.

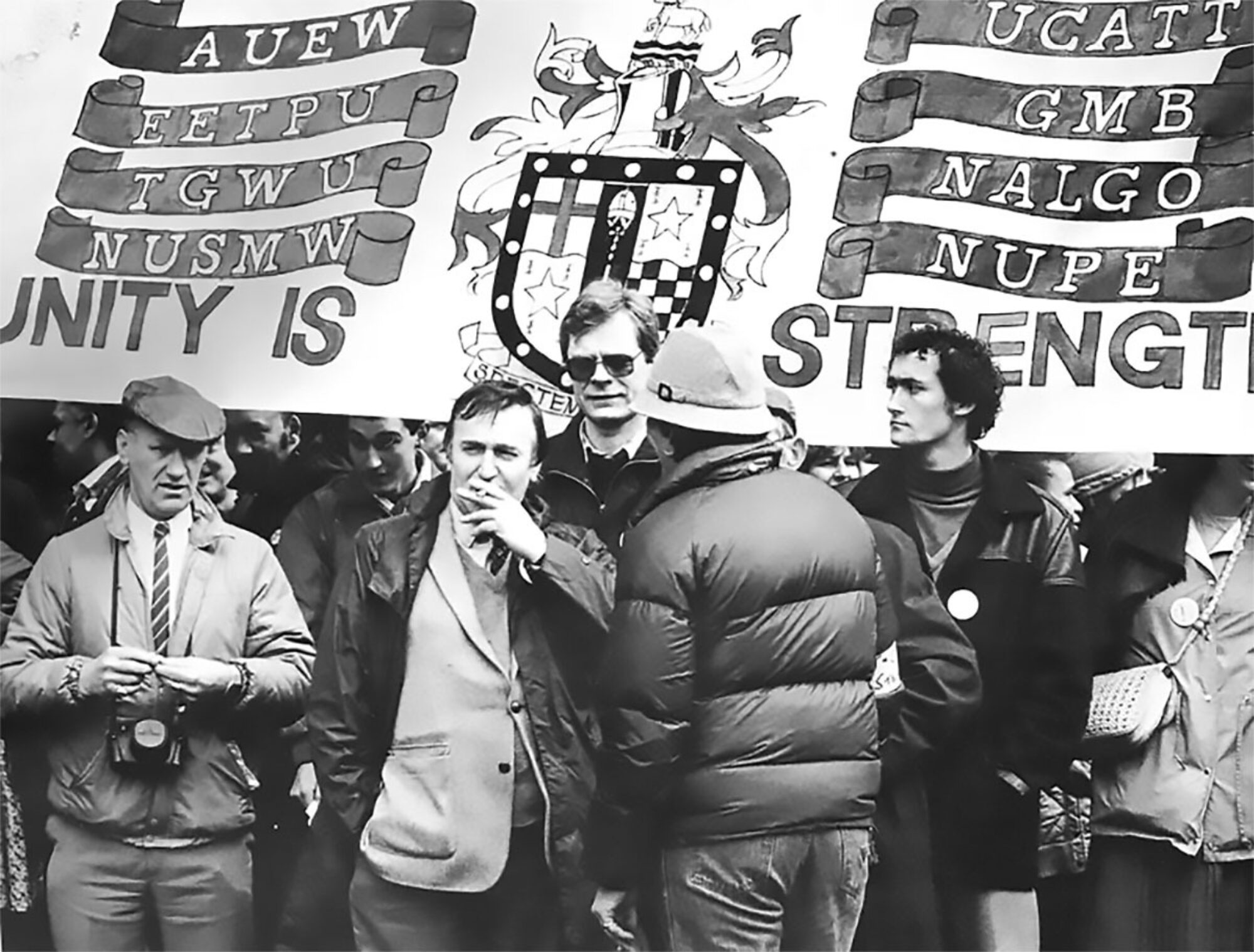

Lambeth Council was led by the charismatic veteran of the radical left, Ted Knight, and when he and his fellow councillors refused to set a rate-cap for the financial year 1985-86, in spite of the legal necessity to do so, the battle lines were drawn. The idea behind this tactic was that by refusing to set a budget for the next financial year, this would force central government to step in to fund local services. Ed had an element of self-interest here, in that he and the other 800 architects, surveyors, clerks of work and typists who made up the department could lose their jobs if the rate-cap was set. Ed became the Unison convener representing himself and his colleagues. There was a march planned from the town hall to Parliament Square and they needed a banner so they asked Ed if he could make one.

“I didn’t worry about how to make it. I could draw and make things and do things,” he says “So, I think I wasn’t just the obvious choice, but the only choice!”

As it had to be made quickly and there wasn’t time to play around with different design ideas, he decided to use the form of a regimental banner. But in place of the battle honours there are the names of all the unions involved in the march and, in the centre, instead of the military crest, there was the coat of arms of Lambeth council. Its motto reads: ‘Judge Me By My Deeds.’

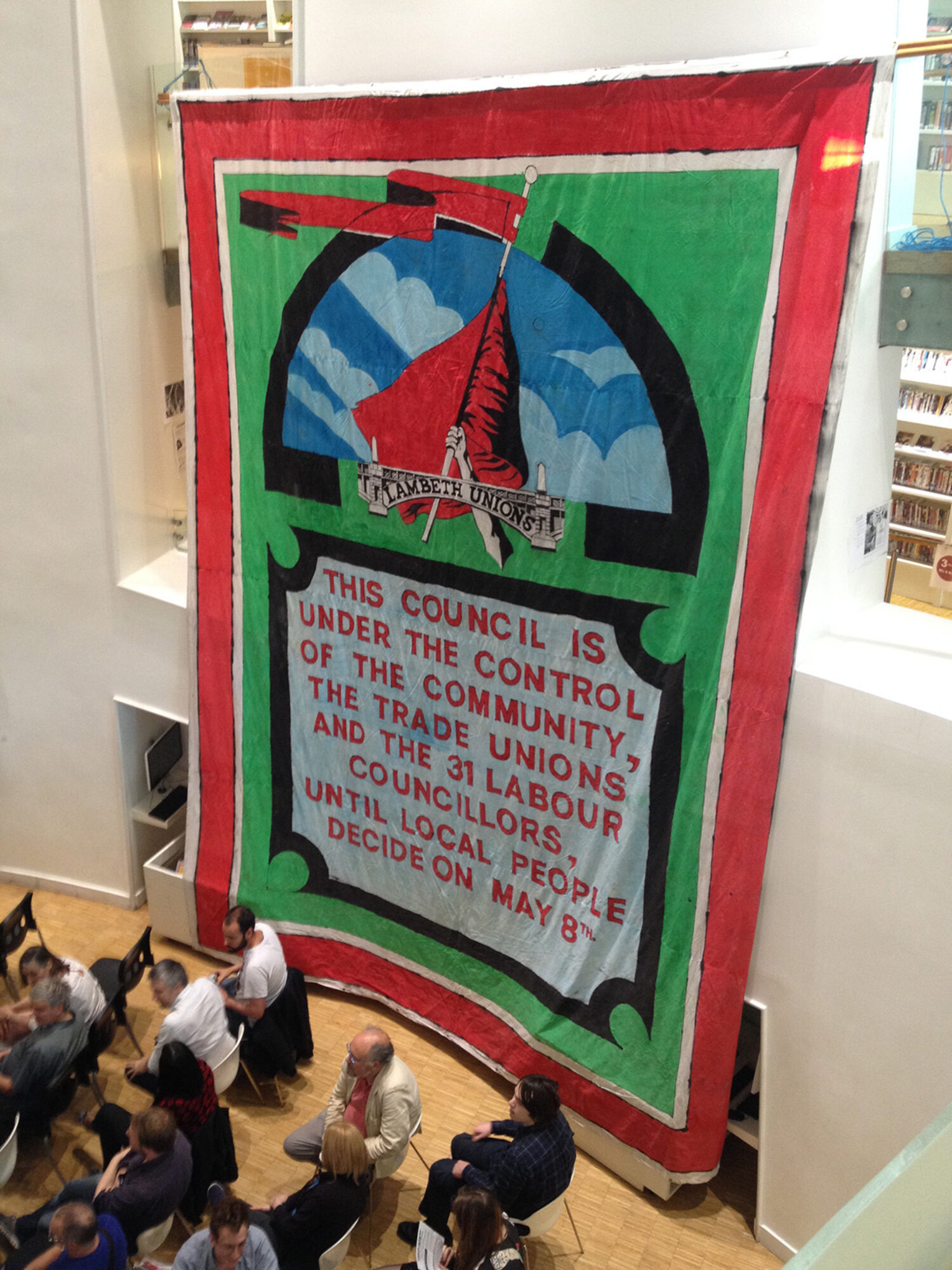

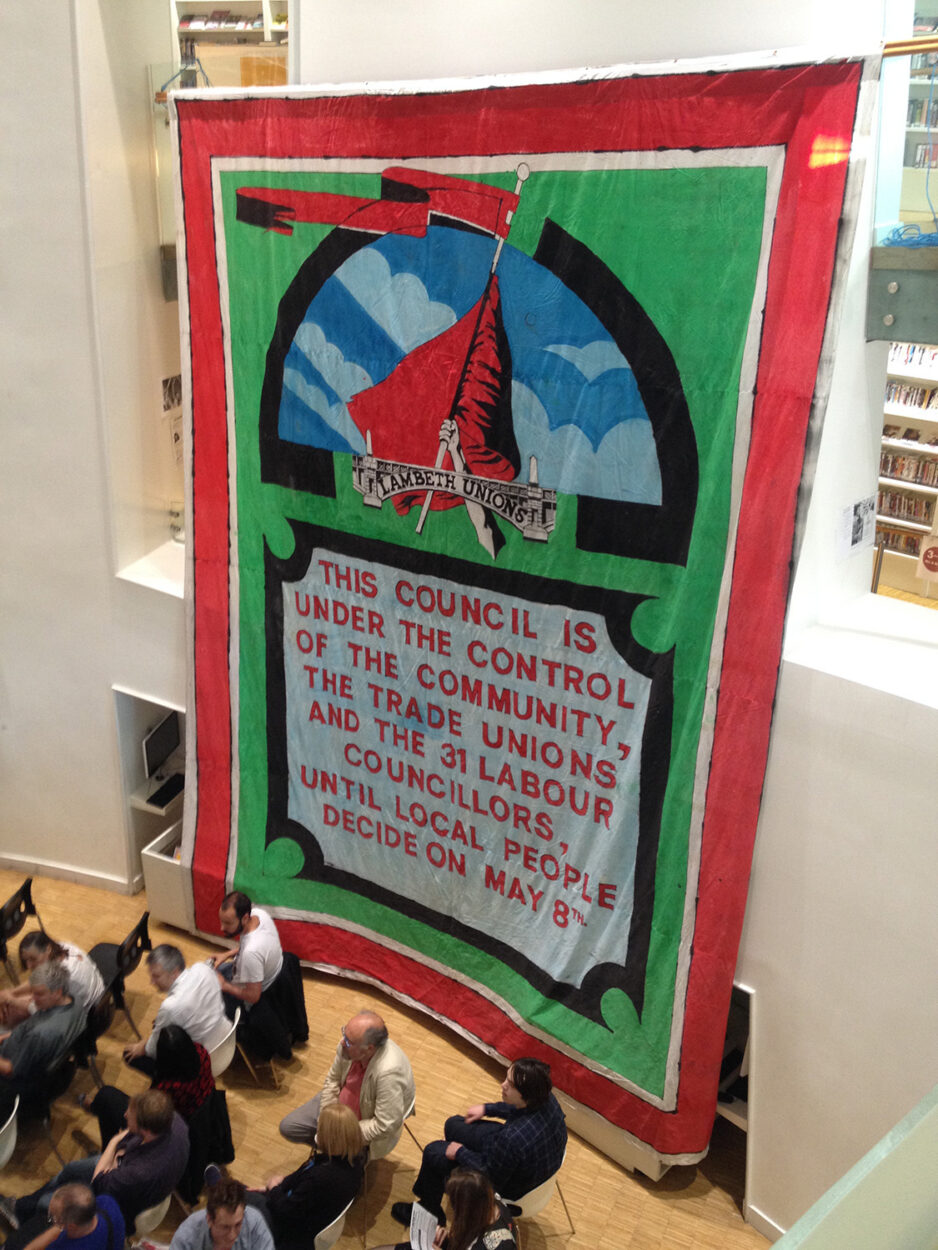

Following the rate-cap rebellion, the Lambeth councillors were surcharged and removed from office and new local elections were held. The unions wanted to keep the momentum of the campaign for adequate council funding going, so Ed designed a giant banner to hang over the clock tower of Lambeth Town Hall. Sylvester Smart, from the Engineering Department, wrote the words while Ed used the motif of Lambeth Bridge to represent the links between the workers and the residents. The giant red flag speaks for itself.

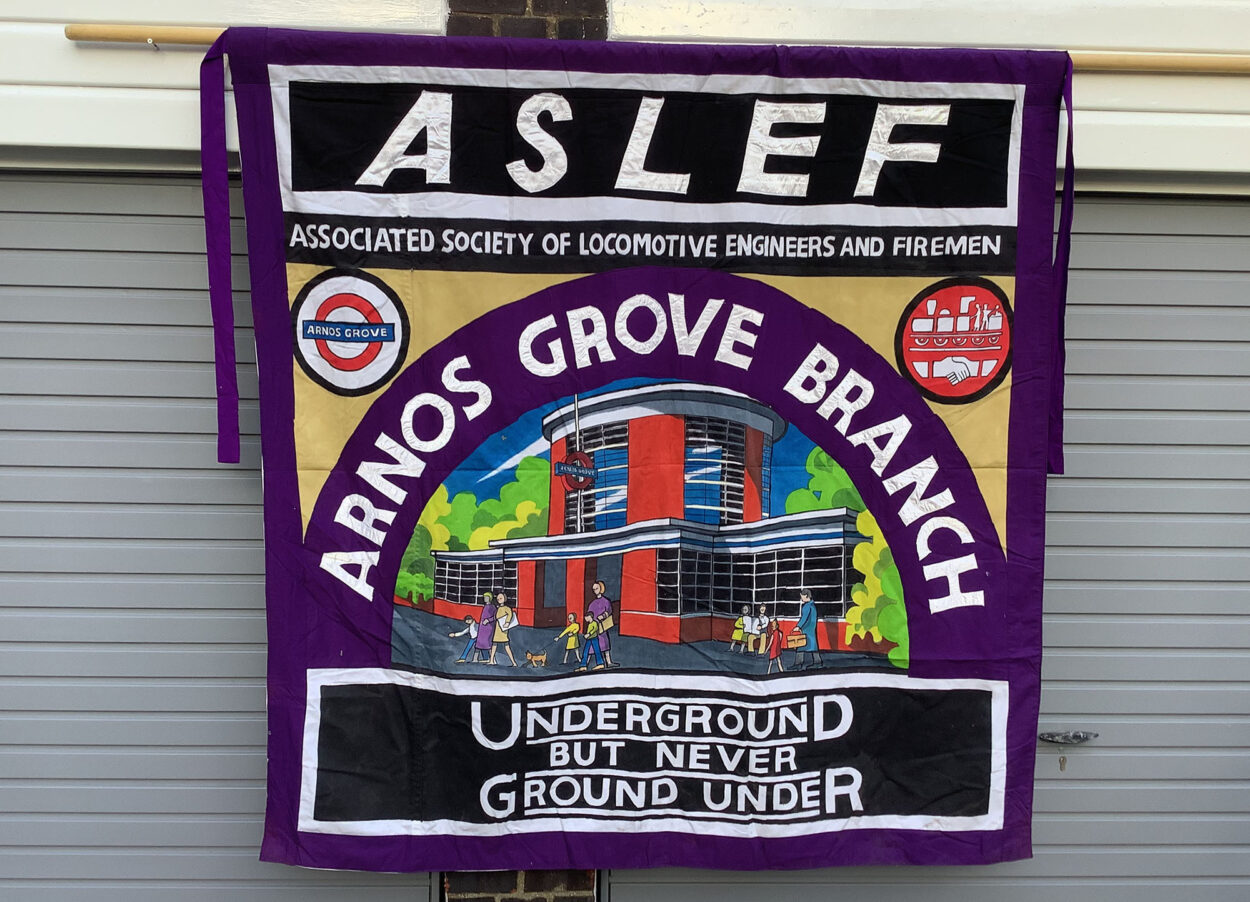

Though the Left is a broad church, the pews are very close together, and word spread that Ed Hall was the man to call if you needed a banner. So as well as continuing to work for the trade unions, he made banners for CND, The Anti-Nazi League, United Families & Friends Campaign (a coalition of campaigns that honoured those who had died in police custody) and the Palestinian Solidarity Campaign among many others. He was still working full time at Lambeth Council, and from 1991 as Unison Branch Secretary, so there were lots of late nights and early mornings in his workshop and that continued until 1997 when he reached retirement age and was able to devote himself full-time to his craft.

On 17 April 1999, a Neo-Nazi militant planted a bomb on Electric Avenue in Brixton. When the device exploded, 48 people were injured, many seriously, because of the nails he’d packed around the it. Alex Owolade from an organisation called Movement for Justice called Ed that evening and asked him to make a banner for a march they were having.

‘I knew Electric Avenue, so I laid it out on the floor and started at the bottom left hand corner then went across and did the scene.’

While Ed was making the banner, another bomb went off in Brick Lane in East London so he quickly adapted the design to include this. By the time a third bomb exploded in the Admiral Duncan pub in Soho, Ed had delivered the banner so no mention of that appears on the finished work.

Later that year, Ed was sitting at Unison’s stand at the Lambeth Country Show with the Brixton Bomb banner on display when a young man came up and asked about it. A few weeks later, he called Ed:

‘Can I include your banner in an exhibition I’m organising?’

’Of course you can.’ Ed said.

‘Where is it? I’ve got a side car on my motorbike so I can bring it along if you like.’

‘Oh, don’t worry, the Tate will come and pick it up.’

The young man was the Turner Prize-winning artist Jeremy Deller who was so struck by Ed’s work that he began asking Ed to work with him; a collaborative relationship that continues to this day.

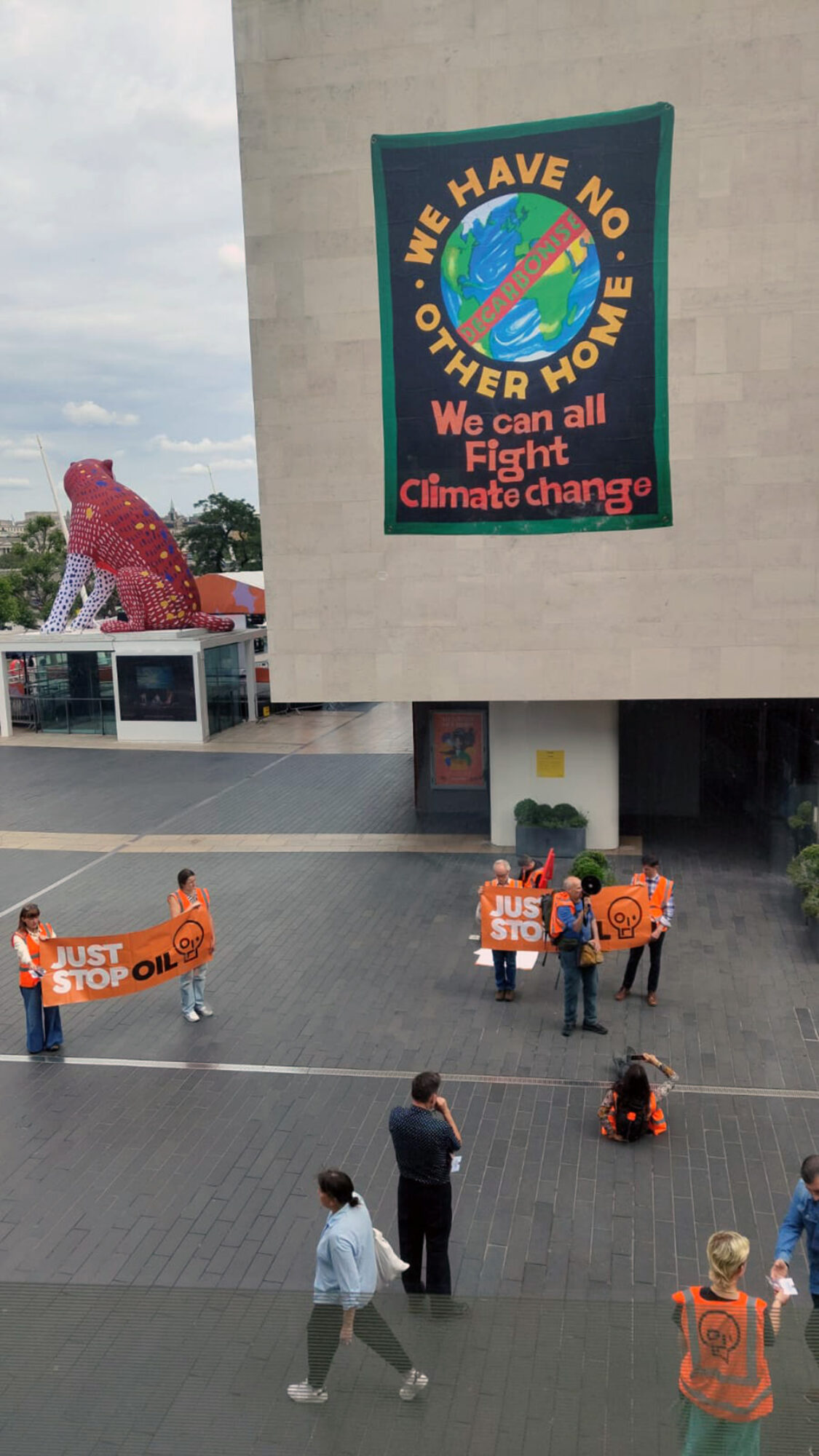

Ed’s most recent work was part of the Southbank’s Planet Summer season which, in conjunction with the Hayward’s Dear Earth exhibition, focussed on the climate crisis. Ed has made three banners, two of which were enlarged and displayed on the exterior of the Royal Festival Hall.

Ed sees his work in the tradition of people like William Morris, Mary Lowdnes, Walter Crane and Edward Burne-Jones, using art and design in promotion of a progressive world view. All he wants to do, he says, is, ‘To make something beautiful and to leave something for the Left that is beautiful.’

Photo: The Lewisohn Archive 2023