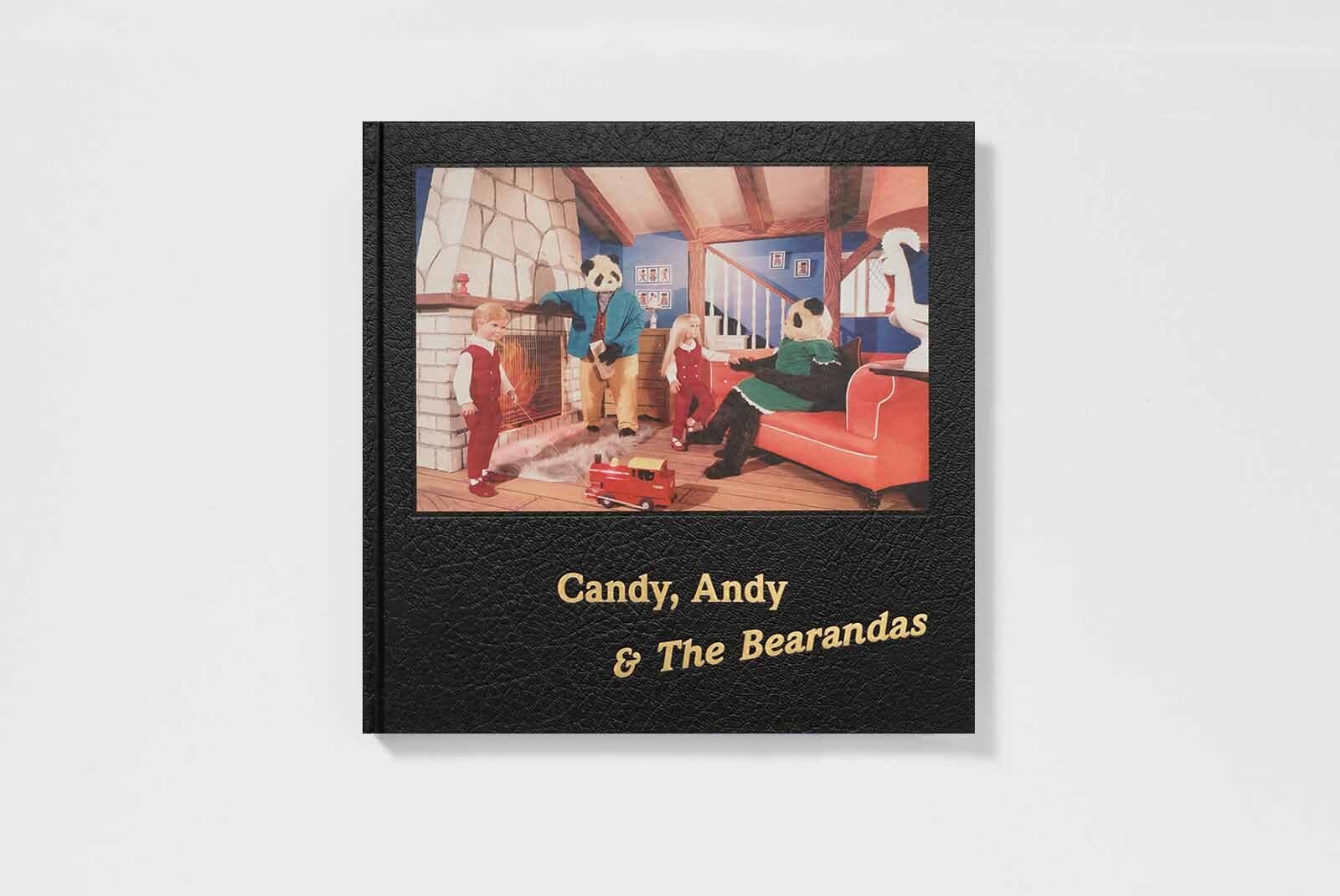

When Alan Dein introduced me to Candy, Andy and the Bearandas in 1993, I was curating the exhibition Who’s Looking at the Family? which opened at the Barbican Art Gallery in London in 1994. Candy and Andy were characters created by Gerry Anderson as photo stories for children: life-size child mannequins who lived with two panda bears – Mr and Mrs Bearanda – in semi-rural suburbia. Candy and Andy’s family, unorthodox as it was, fitted well into the exhibition’s study of family life in Europe and the US, seen through the eyes of critical documentarists and art photographers, revealing the complexities and profundity of the domestic.

For children born and brought up in post-war Britain, familiar stories had a rough edge: JM Barrie’s Peter Pan, an orphan child caught in the limbo of never growing up carried a terrible message of loss and abandonment, while the ordeal of Hansel and Gretel, kidnapped and imprisoned in the heart of the forest, along with other stories collected in 19th century Germany, was familiar bedtime reading. Motherless children, families displaced – all had resonance in post-World War II society. Candy and Andy, looked-after children in the care of two panda bears might have seemed quite unremarkable at a time when family and society were endlessly fractured.

In Eleanor Graham’s 1938 novel The Children Who Lived in a Barn (which appeared in paperback in 1955) five children (ranging in age from seven to thirteen) are left to fend for themselves when their parents travel abroad; evicted from their home by an unscrupulous landlord, they find refuge in a barn, cook, clean and earn money, all the time pursued by a suspicious social worker. Candy and Andy’s lives appear to be less pressured than this, but no less strange. Do the Bearandas look after them or is it the other way round? Whichever it is, the Bearandas do not emerge as model parents – they are large, ponderous and accident prone, far removed from the precise and serene parenting illustrated in the Key Words Reading Scheme Ladybird books for young children, issued in the UK in 1964 and popular for years afterwards. The Bearandas lounge and doze, trip over in the street and break things. It is a bleak-faced Andy who changes the tyre on Mr Bearanda’s Mini and who supervises a group of children to help while Mr Bearanda looks on aimlessly. It is Candy and Andy who gather blackberries alone on a deserted country lane with not a Bearanda in sight. Candy and Andy carry the shopping home carefully while Mrs Bearanda falls in the street, scattering groceries around her. Mrs Bearanda breaks a vase with an umbrella. Mr Bearanda stares baffled at the innards of a broken transistor radio. Candy accepts a box of fireworks from a shifty man in a trilby.

These are mysterious photo tableaux, some of which adapt a simulacrum of the everyday – eating, playing doing small tasks – others of which make no sense at all and some which give a sense of impending crisis and danger. While bright colours and cheerful settings appear throughout, Candy and Andy’s bleak stares and awkward gestures conjure up a macabre puppet theatre, while the Bearandas plod and fuddle and struggle to comprehend it all. The 1950s and 1960s saw increasing societal conflict around parenting as the new and fashionable philosophy of Dr Benjamin Spock, in his 1946 publication Baby and Child Care, collided with traditional and more authoritarian ideas about how to bring up children. Did the Bearandas represent the new hippie parents, and Candy and Andy their independently minded children? Or was the absence of ‘real’ parents and their substitution by bears as carers a reflection on the profound loss and absence still experienced by the post war generation?

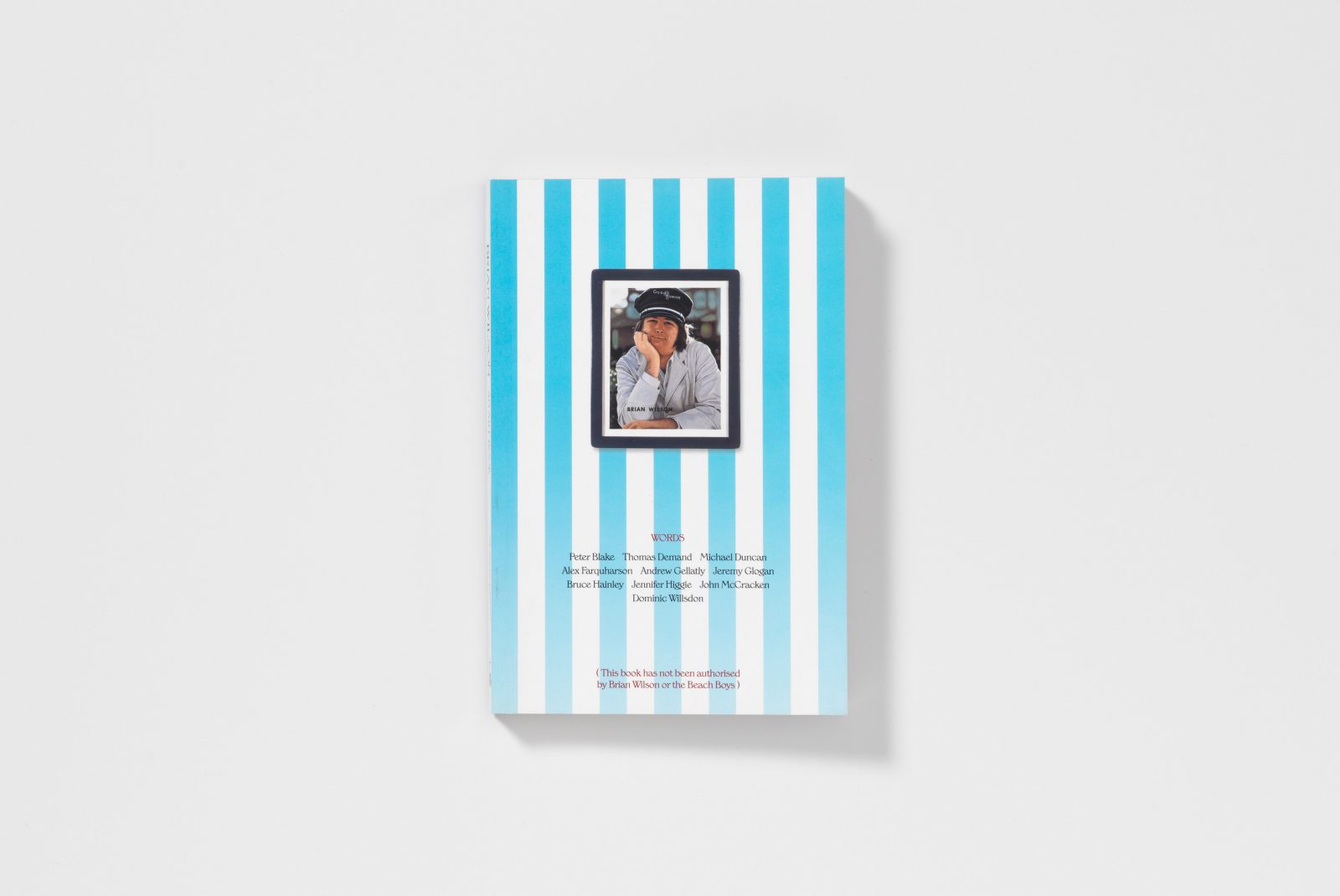

The story of Candy and Andy was told by two photographers, Doug Luke, and Roger Perry, and is set against the background of the emergence of the photo story strip which played a significant part in the proliferating number of teenage magazine titles on the newstands of the 1960s. As Alan Dein has discussed in detail in his introductory essay to Candy, Andy and the Bearandas, Candy was created as a children’s comic book published by Gerry Anderson and his company Century 21. Doug Luke and Roger Perry were both professional photographers, accomplished workers in the film and television industries. Luke was a long-term collaborator of Gerry Anderson and had worked extensively with Anderson’s puppets before the creation of Candy and Andy. Luke had also worked on the Beatles 1965 film Help! so he was well aware of the pop surrealism which was beginning to be so influential in popular culture; in photography’s history many surrealist photographers had used mannequins to explore or challenge the idea of the ‘real’.

The photographs Luke and Perry made are claustrophobic and mysterious – unconscious bears and scheming children – shades of The Children Who Lived in a Barn in their disregard for traditional family ties. There are also shades of John Wyndham’s 1957 novel The Midwich Cuckoos in which a group of children with piercing light eyes and telepathic powers are born to unwitting surrogate mothers. The Midwich Cuckoos and the later film The Village of the Damned (1960) are set in a small English village, not unlike the imagined home of Candy and Andy, to which they eventually migrated after some years spent in a Century 21 studio.

The Candy and Andy stories are almost plotless and entirely visual – a vase is broken, a firework is lit, a meal is set out on the kitchen table. Nothing really happens. Their lives mirrored those of small children, made up of inconsequential incidents and routine. There are no grand narratives, just minor adventures made major by the way we remember childhood. Who would not remember the fall in the street, magnified by the lens of childhood, or the magical day of blackberry gathering, or when the car broke down? Things that adults forget become graven into the memory of a child.

Neither Doug Luke nor Roger Perry attempted to make Candy and Andy and their surrogate parents life-like. They were technicolour figures of the comic book universe - they did not have to be believable - vessels which we fill with our own imaginations. We will continue to wonder how Mrs Bearanda broke the transistor radio and if Mr Bearanda managed to mend it. And who owned the fob watch? Like childhood itself, Candy, Andy and the Bearandas are actors in a theatre of the absurd, gesturing in a language we only just understand, a misremembered mystery.

Photography’s place in the making of narrative for children in the 1960s and 1970s has not yet been explored by scholars of photographic history. Did the photo strips of teen magazines make love and romance more attainable than stories illustrated by drawings? Or just more realistic? Or did they simply contribute to our suspension of disbelief? Photography has the ability to confuse our notions about what is real and what is not, and the photographers employed by Gerry Anderson to bring Candy, Andy and the Bearandas to life, while fully immersed in fictions of the imagination, had no intention of making this strange family in any way ‘real’. While generations of post-war children will have compared their own parents, unfavourably, with the perfect Mum and Dad of the Ladybird books, Candy, Andy, and their ungainly bear parents will remain a rather baffling, and oddly comforting fantasy.

Val Williams is Professor of the History and Culture of Photography at the London College of Communication, University of the Arts London. She is a curator, writer, and educator.